Let’s talk data.

I have mentioned a couple of times that in this project I’ll be using national food balance sheets to assess countries’ diet quality – or how aligned each country’s national ‘diets’ are to a dietary ideal. For those in the business of assessing diet quality, this may induce a shudder, for reasons which I will get into in this post. In sum, we (and others before us) use food supply data as a proxy for diets at a global level because quite simply, there isn’t (good) enough food consumption data available to compare across countries. Like cooking from the pantry, we have to use the best of what we’ve got –particularly when we don’t have enough time or resources at our disposal to get new ingredients.

What is used to measure diet quality?

In my second post (during my early reading of the literature) I explored the broad field of dietary pattern analysis but I didn’t really get into how researchers gather the information they use to characterise a dietary pattern and/or measure adherence to dietary guidelines or diet quality indices.

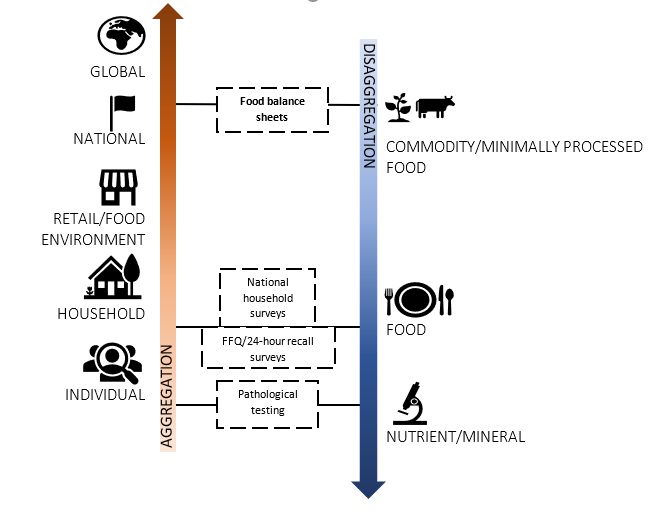

Here’s how I see the range of available dietary data collection methods: at the top of the ‘ladder’ we have highly aggregated measures like food balance sheets which, with enough supporting information (and some assumptions), can be disaggregated in terms of food composition from a commodity to a nutrient-level, but cannot be disaggregated by consumption of the population; at the bottom we have pathological testing for nutrient intake or status in the body which can be aggregated (with enough data) for a population up to a national or global level, but cannot be aggregated by food or commodity. In the middle sit household and individual food consumption surveys. These methods are at a food level, though individual studies may be supported by clinical or pathological testing and may be aggregated by population and with supporting information, disaggregated by nutrient composition.

According to Vandevijvere et al., 2013 across these three tiers of data, food supply data constitutes the ‘light touch approach’. Alternatively, Micha (2008) referred to most previous global analyses of dietary habits using ‘crude national estimates’ from food balance sheets, or expenditure data such as Household Consumption and Expenditure Surveys. Unfortunately, there are problems with using food consumption data at all levels. The quality of a single source, the quantity of available quality sources, and how to standardise or compare their data can each, or together, be at issue.

The question for us using food balance sheets then becomes – do we use these studies to develop a validation calculation, to draw down the estimate of actual consumption? Or, do we call it like it is and not claim to be assessing the quality of country dietary intake at all? My preference at this point is for the latter. Even if we are to re-estimate consumption based on studies comparing dietary estimates between food balance sheets and surveys, there is so much heterogeneity, and unresolved issues with surveys anyway that it is perhaps best not to stack up estimates – and further obscure the complexity of food systems by trying to simplify them.

In this project then I would tend to call a spade a spade – and use it for that purpose. We are using food supplies, so let’s say that we are considering the ‘quality’ of food supplies or availability itself, not as a proxy for diets, but as a distinct component of food systems. From a policy point of view this remains a valid exercise. The intent is that with this benchmark, we can first consider the systems interventions that could help to bring food supplies (and environments) more in line with dietary ideals—for health or sustainability—or, where we find that these supplies are aligned with dietary ideals, we can better understand the influence of other factors in driving unideal consumption. As Herforth and Ahmed (2015) put it ‘broadly, what is available is consumed’, and while the relationship between food availability and consumption is complex and bi-directional – food cannot be consumed if it isn’t available. The kinds of foods that are produced and made available to consume, and in what quantities, is measurable. While the data we have certainly isn’t perfect, it’s a good place to start.