Last week I wrote a bit about food systems approaches, to contextualise my project: why we’re looking at diets, and why looking at diets isn’t enough to transform food systems alone. At least, that was my intention, I’m not too good at keeping my thoughts on track…

Anyway, rather than blowing out that post even more than I already had, here is an update of sorts following the recent online release of Christophe Béné and company’s new review article: ‘Understanding food systems drivers: A critical review of the literature‘ in Global Food Security. Interesting for me (at least), most of these authors are just across the courtyard and also in the Decision and Policy Analysis team at CIAT.

The basic premise of this paper is that work is progressing on the food systems concept across both academia and policy (as discussed in my previous blog), but the characterisation of the drivers of food systems change has so far been pretty sloppy. The key issues the authors seek to address are:

- definition—what is a driver anyway? What is it not?

- overlap—what are the distinct drivers? Is there data to support their role as a driver?

- behaviour—what do they influence in the food system, and how?

Essentially, the authors seek to target the ‘shopping list’ tendency when describing the kinds of things that may influence change in food systems. From a policy perspective, when we want to find leverage points to bring about change in the system (i.e. towards better health or environmental outcomes), it is not particularly useful to just list of a range of potential drivers in the system, without explaining what they are, showing what in the system they affect, and how. From there, policy-makers and others have a more representative (though high-level and simplistic) framework within which to model the effect of proposed interventions: will it strengthen the influence of a particular driver on particular outcomes, or reduce it?

We propose that ‘drivers’ of food systems be defined as “endogenous or exogenous processes that deliberately or unintentionally affect or influence a food system over a long-enough period so that their impacts result in altering durably the activities, and subsequently the outcomes, of that system”.

Béné et al., 2019

Presenting food systems dynamics

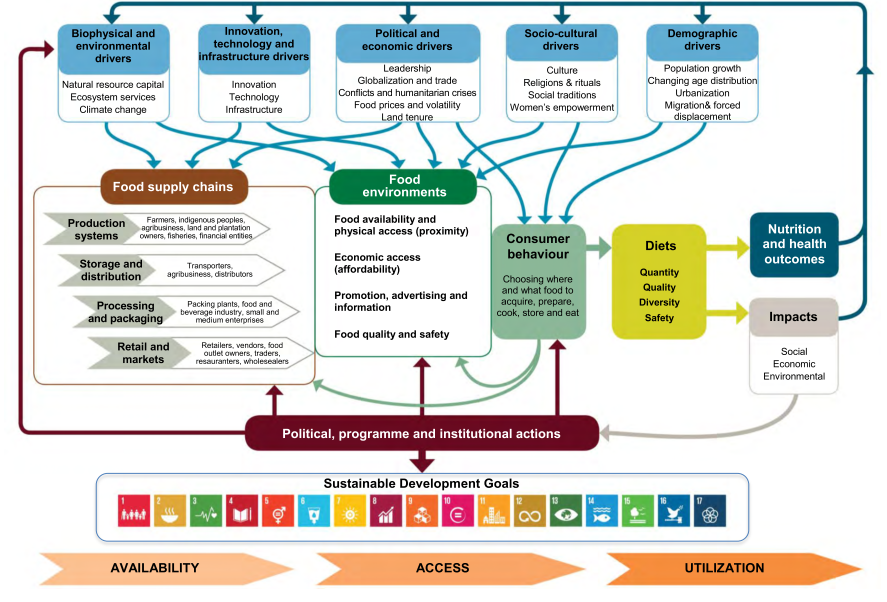

Béné and colleagues also built on previous work (like that below) in presenting food systems interactions by proposing a(nother) conceptual framework of food systems (above). They present the 12 key identified drivers in three themes: production/supply; distribution/trade; and consumption/demand. These drivers are depicted as having durable effects on food systems actors and activities, which in turn have feedback effects on the drivers. Food systems outcomes also feedback into the production/supply and consumption/demand drivers, which both interact with the distribution/trade drivers.

HLPE’s Conceptual framework of food systems for diets and nutrition (2017)

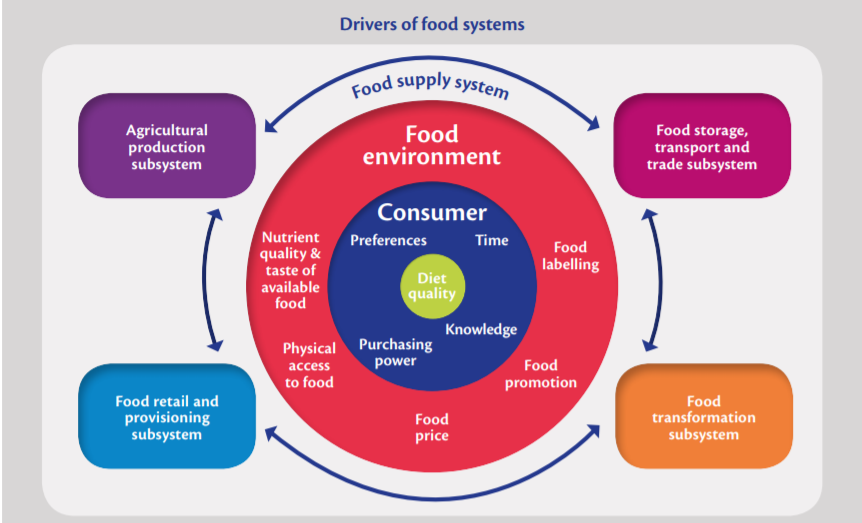

GloPlan’s

Relationship between diet (quality) and food systems (2016)

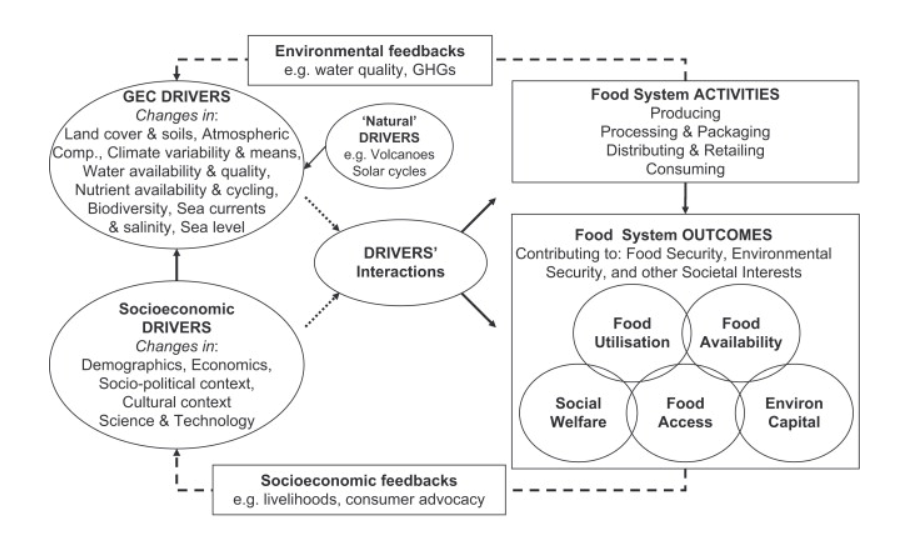

Eriksen’s Food systems and their drivers (2008).

This presentation differs in its categorisation of drivers according to their effects on the three core elements of the ‘food chain’: production, distribution and consumption (or supply, trade, demand). Others have organised drivers according to their general character, whether they related to changes in environmental, social, economic, technology/infrastructure, etc. They are put in the ‘driver’ group as they represent measures for which a change in state can be observed. It may be useful to leave this group somewhat open-ended to allow for changes in the relative importance or influence of particular factors to a particular community or its environment (e.g. drought cycles in some areas vs flooding in others). But, on the other hand, this style of grouping might lend itself to simply plonking drivers ahead or outside of the system activities, where their particular influences on the ‘internal’ systems dynamics (and how these could be leveraged) can be overlooked.

I’ll be interested to see how this new conception of food systems dynamics is received in the research community—including how it may be adapted for other ‘views’ (systems of interest or intervention points) within the food system, such as diets and food production and supply. Especially since there’s certainly a tricky line between making something fit-for-purpose and reinventing the wheel!

-A