They say you are what you eat. If you eat unhealthy foods, you damage your body;

“to much salt is bad for the heart”

“don’t eat too much sugar, it’s bad for your teeth”

“a moment on the lips, a life time on the hips”

Eat healthily and your body will thank you for it;

“an apple a day keeps the doctor away”

“drink milk, it’s good for your bones”

“red meat is good for iron”

However, most of us are unaware that what you eat also impacts the environment. We know that eating healthily/unhealthily impacts your body but few know the damage it has on the planet!

How can your eating habits be connected to climate change?

Animal product are of particular concern for climate change[1, 2]. Livestock production is the largest contributor to agriculture’s carbon footprint, estimated to account for 14% of anthropogenic emissions, with animal feed production/processing and enteric fermentation accounting for 45% and 39% respectively [3].

The greenhouses gases attributed to that steak you ate can be several times more than eating the equivalent weight in vegetables, legumes, beans or pulse [2, 4, 5]. The carbon footprint of meat, beef in particular can be anywhere from 3 to 10 times larger than that of pig-meat or chicken [6] Why the large range, because the carbon footprint is dependent on the production systems for beef. For example, livestock production in South America, particularly in Brazil and been linked with deforestation. Over 3 million hectares per year of tropical rainforest is lost, 70% of which is occurring in Latin America [7].

Livestock production is also a big user of water, with the average 150 gram beef burger utilizing 2400 litres of water and a 200ml glass of milk using up to 200 litres of water [8]. An important fact to consider since ‘water crisis’ is among the top 3 big ‘risks’ list from the World Economic Forum (WEF) at Davos’ since 2014.

Eating for health and environment;

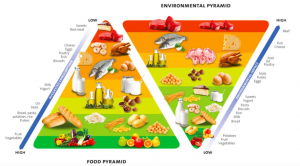

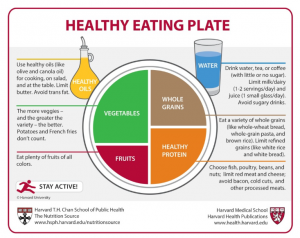

If you want to make a difference, in reality a vegan diet is the most environmentally sustainable [9] with vegetarian diets coming second [9, 10] both can still meet the nutritional requirements of humans. However, education on what to eat and how to eat vegan/vegetarian is one of the biggest barriers to change [11]. That is not to say that cultural, tradition and consumer behaviour change aren’t also barriers to change. They too have a large role to play in stalling transitions to sustainable diets. But then again, what is a sustainable diet? Researchers have been endeavouring to define the ‘sustainable diet’ and some have developed ‘guidelines’ and food pyramids.

Double Pyramid: Barilla Centre for Food & Nutrition Foundation (BCFN Foundation) Harvard Eating Plate

Nonetheless, the term sustainable is often dependent on how it is defined and so to are sustainable diets. Should environmental, health, social and economic issues take precedent? How do we give equal weight to each? Can we give equal weight to each and still meet the requirements of health? Can a environmentally sustainable diet also help meet socio-economic goals (for example almost 60 million poor small-holders rely on livestock production [3, 12, 13]).

These are just some of the questions researchers are considering. Nevertheless, one message is clear, current consumption levels of animal products are not sustainable in the context of climate change. An issue further amplified by the growth and demand of animal products in developing countries. However, the bulk of responsibility for changing diets lies with developed nations.

Reference (numbered) link: http://www.plantagbiosciences.org/people/sinead-moran/bibliography/

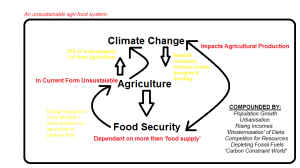

Climate change also directly hinders the ability of agriculture to meet future food demands. It jeopardises the natural resources, water, biodiversity and soils on which agriculture relies and as such may see a material geographical shift in the production of soft commodities [5]. Moreover, climate change will result in deteriorating yields in some crops [2, 7, 14] and create harsher and more unpredictable conditions for producing agricultural commodities.

Climate change also directly hinders the ability of agriculture to meet future food demands. It jeopardises the natural resources, water, biodiversity and soils on which agriculture relies and as such may see a material geographical shift in the production of soft commodities [5]. Moreover, climate change will result in deteriorating yields in some crops [2, 7, 14] and create harsher and more unpredictable conditions for producing agricultural commodities.