In this post I will walk you through how I put together an inventory for LCA. I use margarine as an example here.

I wanted to find out the carbon footprints associated with producing margarine globally. After doing some researching of margarine products online, I realized there is no *one * standardized way to produce margarine, the ingredients vary from country to country and also among margarine producers…so I decided to do my LCAs based on all the formulations I could find, and then I would calculate an average value based on the global warming potential I calculated for each formulation.

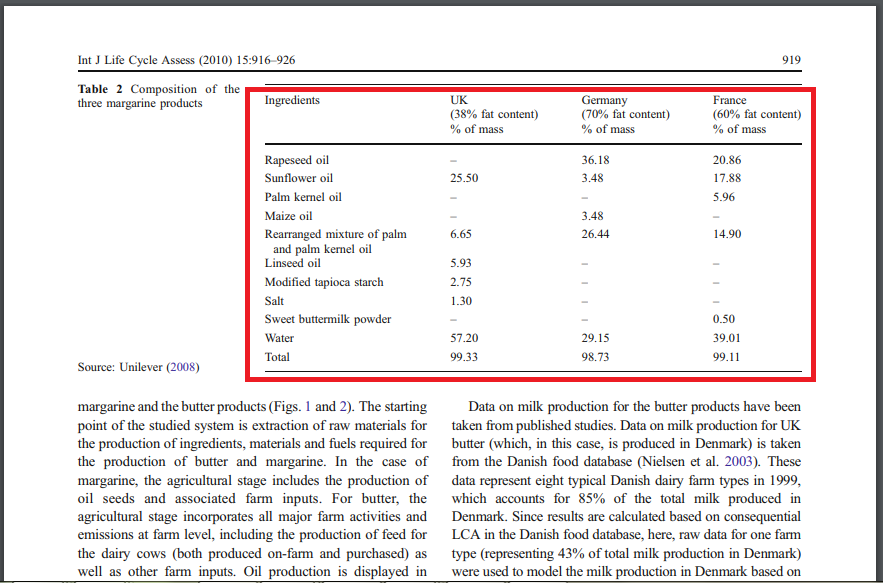

Firstly, I searched for LCA studies on margarine- and I found one that one included detailed information on the composition of 4 different margarines products (from 4 different European countries):

Next, I looked for more formulations online…

It was hard to find more detailed margarine formulations, as margarine products often consisted of multiple edible oil varieties (such as soya oil, palm oil/palm kernel oil, sunflower oil,etc.) and while the percentage of total edible oils used was given in the ingredients list, I had no idea how much of each was used to produce the margarine.

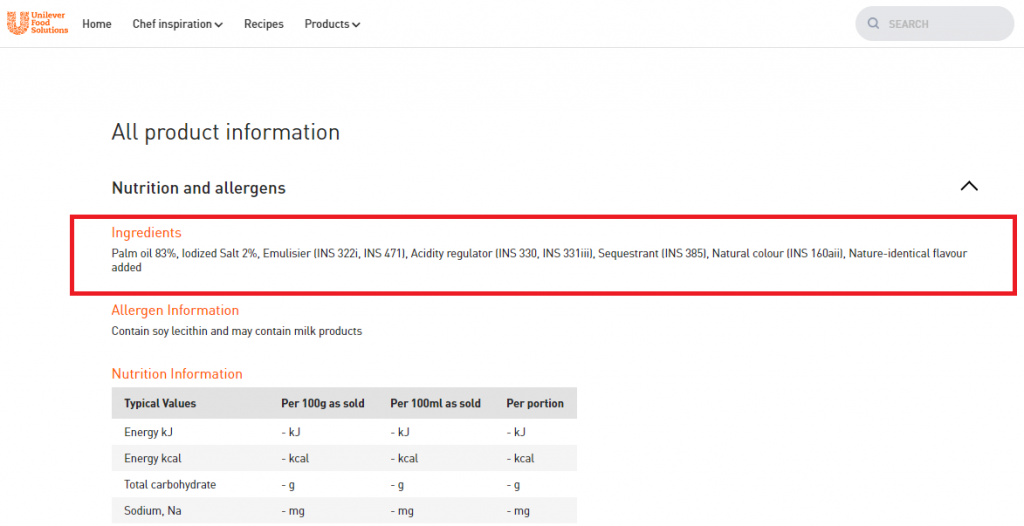

Eventually, I found one product that had only one edible oil ingredient- margarine made of palm oil here.

It didn’t specify amounts for food additives…so I made the assumption that the amounts of food additives added were low, and therefore overall impact would be low as well.

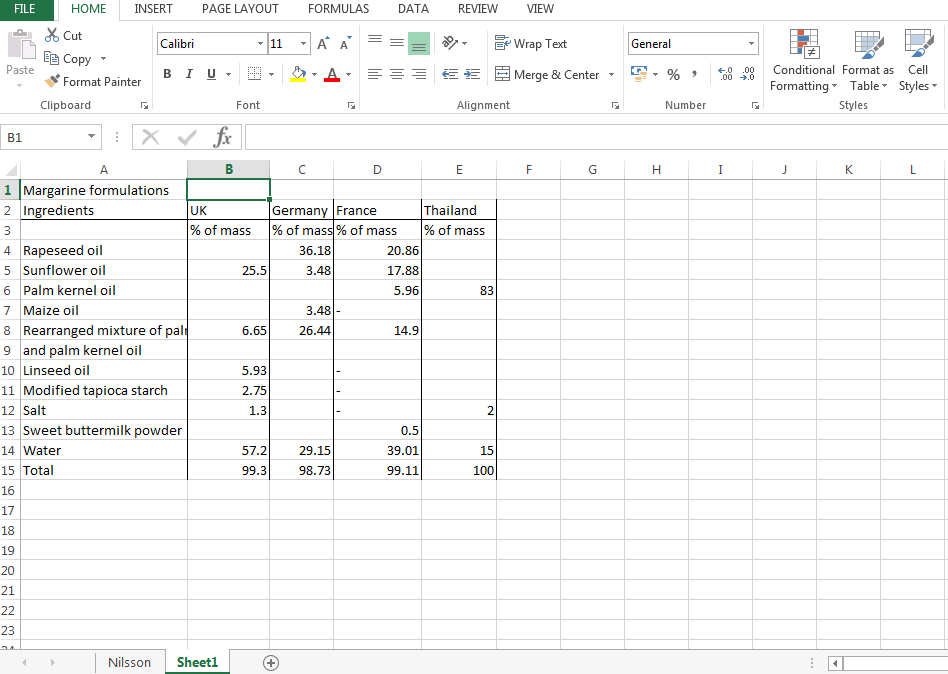

In the end I had margarine formulation data for 4 countries and put them all in one Excel file.

I worked out the amounts needed to produce one tonne of margarine using each country’s formulation, and then multiplied that by the carbon footprint data per kg of the respective product from LCA databases.