The United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), (2021) defines food waste “as food and the associated inedible parts removed from the human food supply chain” in the retail food service and household sectors. UNEP, (2021) reported that in 2019, 932 million tonnes of food was wasted with 61% being generated by households, 26% from food service and 13% from retail. 17% of global food production is wasted (11% from households, 5% from food service and 2% in retail) (UNEP, 2021).

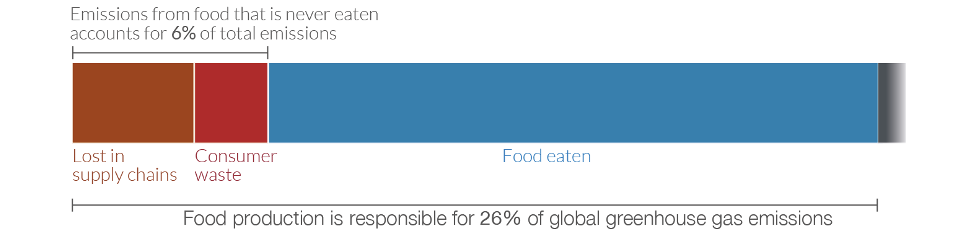

This food waste comes with an environmental price with 6% of global greenhouse gas emissions being produced by food waste (Figure 1) (Ritchie and Roser, 2020). This waste also comes with a financial cost of on average 990 billion US Dollars (US$) annually (UNEP, 2022). The food with the highest wastage rates are fruit and vegetables including roots and tubers with on average 40-50% of these being wasted annually (UNEP, 2022). Figure 2 below shows an estimate of countries with the highest rates of food waste by sector.

Food waste varies between countries with it being influenced by factors such as level of income, urbanisation and economic growth (Chalak et al., 2016, Ishangulyyev et al., 2019). Developing countries produce a lot less food waste (44% of global food loss and waste). Waste in developing countries is generated mainly in post-harvest and processing due poor practice, technological limitations, labour and financial restrictions and lack of infrastructure (Gustavsson et al., 2011, Ishangulyyev et al., 2019). Waste in developed countries (56% of global food loss and waste) mainly comes from the consumption stage of the supply chain (Gustavsson et al., 2011, Ishangulyyev et al., 2019). A large proportion of food is wasted after preparation, cooking or serving. Another huge contributor to food waste in developed countries is as a result of food not being consumed before the expiration date (Bond et al., 2013, Priefer et al., 2013, Ishangulyyev et al., 2019).

With such a high percentage of food wasted globally this blog post aims to look at the environmental impact of this food waste and what measures are in place in order to reduce this impact.

Environmental Impact of Food Waste;

The FAO estimates that food waste contributes to 3.3 billion tonnes of CO2eq (carbon dioxide equivalent) every year (Scialabba et al., 2013). Often enough when food is wasted it goes to landfill where it produces large amounts of methane emissions (World Wildlife Fund (WWF), 2022). Methane is a much more potent GHG with it being 80 times more powerful than CO2 in terms of its ability to absorb the suns radiation which overall causes our atmosphere to warm (NatureFood, 2021). However, this gas does have a shorter atmospheric lifespan of 10 years which means that methane reduction is our greatest potential to reduce GHG emissions in a short span of time (NatureFood, 2021). Therefore by reducing our global food waste we have the potential to cut these associated methane emissions which will have a big impact over a shorter period of time.

Food production is responsible for 26% of global GHG emissions (Hannah Ritchie, 2019). When we waste food we also waste the energy and inputs used to harvest, transport, produce and package each product and these all come with an environmental cost and contribute even further to increasing GHG emissions and environmental degradation (Ritchie and Roser, 2020). This means that when we waste food we also waste these inputs and produce unnecessary emissions which contributes to our warming and changing climate.

In terms of environmental footprints associated with global average per capita per day food waste, Chen et al. (2020) calculated them to be 124g CO2eq., 58 litres of freshwater use, and 0.32m2 of cropland use. This means by reducing our food waste we can reduce these daily environmental impacts.

How to Reduce Food Waste;

FAO (2022) suggest to only buy what is needed to in order to reduce food waste. This can be done by making a meal plan, checking what is there before going shopping and by writing a shopping list (Environmnetal Protection Agency (EPA), 2022). Another way to reduce food waste is to save your leftovers by using them in another meal or freezing them saving them for another time instead of storing them and letting them go stale and throwing them out (EPA, 2022, FAO, 2022, Lipinski, 2013). More effective ways to reduce food waste is to cut portion sizes and understand food labelling (For example the difference between best-before and use-by dates) (FAO, 2022, Lipinski, 2013).

Another way to reduce the GHG impact of food and food waste is by buying local (this will reduce the distances the food needs to travel in order to get to the consumer and therefore reduce associated emissions with long journeys (van Goeverden et al., 2016, FAO, 2022).

Hanson et al. (2019) suggests three different approaches which have interventions to reduce food waste, the whole supply chain approach, specific hotspots approach and an enabling conditions approach. Under the supply chain approach Hanson et al. (2019) proposes 3 interventions under the whole supply chain approach;

- To develop national strategies to reduce food loss and waste.

- To create national public and private partnerships.

- To launch a “10x20x30” supply chain initiative where at least 10 leading players commit to a target-measure act to engage with large suppliers to see a 50% reduction in food loss and waste by 2030.

Hanson et al. (2019) suggests 4 interventions under the specific hotspots approach;

- Push efforts to strengthen value chains to reduce smallholder losses

- Launch a “Decade of storage solutions”

- Shift social norms and behaviour

- Reduce GHG emissions

Finally under the enabling conditions approach Hanson et al. (2019) recommended 3 interventions;

- To scale up financing

- To overcome the data deficit

- To advance the research agenda.

The European Commission (2022) aim to set out legally binding targets in the EU by the end of 2023 in order to reduce food waste. By the end of 2022 they also aim on revising the EU rules on date marking in relation to ‘use by’ and ‘best before’ dates.

Certain plans and strategies have food loss and waste prevention included in their aims. These include the EU commissions farm to fork strategy, certain national food waste strategies such as Italy's and Ireland's (Azzurro and GaianiS, 2016, Department of the Environment, 2022).

In 2016, France seen the introduction of a law to reduce food waste which saw French supermarkets banned from destroying unsold food products and instead have to donate it (Zero Waste Europe). We also see new innovations such as the “Too good to go App” which sees food from cafes, restaurants, hotels, shops and manufacturers being sold at the end of the day for a discounted price instead of before out the food (Too Good To Go, 2022).

In conclusion food waste contributes to the environmental problems and degradation we are experiencing in today’s world. There is initiatives and plans set up to address this however, tons of food gets wasted on a daily basis. In order to eliminate food waste more needs to be done on both the consumer and governmental level to reduce this waste and associated GHG emissions.

AZZURRO, P. & GAIANIS, V. M. 2016. Italy-Country report on national food waste policy. Food policy, 46, 129-39.

BOND, M., MEACHAM, T., BHUNNOO, R. & BENTON, T. 2013. Food waste within global food systems, Global Food Security Swindon, UK.

CHALAK, A., ABOU-DAHER, C., CHAABAN, J. & ABIAD, M. G. 2016. The global economic and regulatory determinants of household food waste generation: A cross-country analysis. Waste Manag, 48, 418-422.

CHEN, C., CHAUDHARY, A. & MATHYS, A. 2020. Nutritional and environmental losses embedded in global food waste. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 160, 104912.

DEPARTMENT OF THE ENVIRONMENT, C. A. C. 2022. Ireland’s National Food Wste Prevention Roadmap.

ENVIRONMNETAL PROTECTION AGENCY (EPA). 2022. Preventing Food Waste [Online]. EPA. Available: https://www.epa.ie/take-action/in-the-home/circular-economy-/food-waste-prevention/ [Accessed 24/08/2022].

EUROPEAN COMMISION. 2022. EU Actions Against Food Waste [Online]. European Commission. Available: https://food.ec.europa.eu/safety/food-waste/eu-actions-against-food-waste_en [Accessed 25/08/2022].

FAO. 2022. 15 Quick Tips for Reducing Food Waste and Becoming a Food Hero [Online]. FAO. Available: https://www.fao.org/fao-stories/article/en/c/1309609/ [Accessed 24/08/2022].

GUSTAVSSON, J., CEDERBERG, C., SONESSON, U., VAN OTTERDIJK, R. & MEYBECK, A. 2011. Global food losses and food waste. FAO Rome.

HANNAH RITCHIE. 2019. Food Production is Responsible for One-Quarter of the World’s Greenhouse Gas Emissions. [Online]. OurWorldinData.org. Available: https://ourworldindata.org/food-ghg-emissions[Accessed 24/08/2022].

HANSON, C., FLANAGAN, K., ROBERTSON, K., AXMANN, H., BOS-BROUWERS, H., BROEZE, J., KNELLER, C., MAIER, D., MCGEE, C. & O’CONNOR, C. 2019. Reducing Food Loss and Waste: Ten Interventions to Scale Impact.

ISHANGULYYEV, R., KIM, S. & LEE, S. H. 2019. Understanding Food Loss and Waste-Why Are We Losing and Wasting Food? Foods, 8.

LIPINSKI, B. 2013. 10 Ways to Cut Global Food Loss and Waste [Online]. World Resources Institute (WRI). Available: https://www.wri.org/insights/10-ways-cut-global-food-loss-and-waste [Accessed 25/08/2022].

NATUREFOOD 2021. Control methane to slow global warming - fast. Nature, 596, 461.

PRIEFER, C., JÖRISSEN, J. & BRÄUTIGAM, K. 2013. Technology options for feeding 10 billion people. Options for Cutting Food Waste. Science and Technology Options Assessment, European Parliament, Brussels, Belgium.

RITCHIE, H. & ROSER, M. 2020. Environmental Impacts of Food Production [Online]. OurWorldInData.org. Available: https://ourworldindata.org/environmental-impacts-of-food#citation [Accessed 24/08/2022].

SCIALABBA, N., JAN, O., TOSTIVINT, C., TURBÉ, A., O’CONNOR, C., LAVELLE, P., FLAMMINI, A., HOOGEVEEN, J., IWEINS, M., TUBIELLO, F., PEISER, L. & BATELLO, C. 2013. Food Wastage Footprint: Impacts on Natural Resources. Summary Report.

TOO GOOD TO GO. 2022. Too Good To Go, [Online]. Available: https://toogoodtogo.ie/en-ie [Accessed 24/08/2022].

UNEP. 2022. Think-Eat- sAve Reduce your Footprint; Worldwide Food Waste [Online]. UNEP. Available: https://www.unep.org/thinkeatsave/get-informed/worldwide-food-waste [Accessed 24/08/2022].

UNITED NATIONS ENVIRONMENT PROGRAMME (UNEP) 2021. Food Waste Index Report 2021.

VAN GOEVERDEN, K., VAN AREM, B. & VAN NES, R. 2016. Volume and GHG emissions of long-distance travelling by Western Europeans. Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment, 45, 28-47.

WORLD WILDLIFE FUND (WWF). 2022. Fight Climate Change by Preventing Food Waste [Online]. WWF. Available: https://www.worldwildlife.org/stories/fight-climate-change-by-preventing-food-waste[Accessed 24/08/2022].

ZERO WASTE EUROPE. U/D. France’s Law for Fighting Food Waste; Food Waste Prevention Legislation [Online]. Zero Waste Europe. Available: https://zerowasteeurope.eu/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/zwe_11_2020_factsheet_france_en.pdf [Accessed 25/08/2022].