COP26 took place in Glasgow from 31st October to the 13 November 2021 where there was numerous pacts and agreements made in order to work towards and reach net-zero emissions by 2050. Net-Zero is where we must work towards in order to reduce our emissions and reverse and halt further impact of climate change (University of Oxford, 2022). This goal is set to be achieved through a number of actions and pacts such as the Glasgow Climate Pact (Carver, 2022). However 10 months on from this monumental conference have we actually seen any developments or achievements of any of the goals set out by our world leaders?

- To speed up the phasing out of coal

Harvey (2022) reports that this goal is not being achieved and is highly unlikely to be achieved with new evidence emerging that coal production and use is increasing again in the COVID-19 recovery and in the mist of the Ukrainian-Russian war (Harvey, 2022). Big coal users and producers such as Russia and China refused to agree to the “phasing out” of coal however did change it to the “phasing-down” of coal (Harvey, 2022). Hoog and Kirk (2021) and The Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air (CREA) (2022) state that coal is not being phased out quick enough in order to meet the goals set at COP and to reduce GHG emissions. Figure 1 below shows us that countries have committed and set dates to phase out coal however, they are years down the line and at that rate it could be too late. Parra et al. (2019) and (Wang et al., 2021) highlights that in order to achieve the 1.5oC limit we would need to see an 80% reduction in coal generation by 2030 based on 2010 levels with a complete phase out being seen by 2040. However, with major coal burners such as Australia, China, India and the US not signing up to the deal combined with the delay on set of the phasing out, this goal may not be achieved which could hamper the achievement of net-zero.

2. Reducing or limiting deforestation

At the conference over 100 leaders committed to ending deforestation by 2030 (Rannard and Gillett, 2021). Deforestation effects warming and climate change in two ways; the first being that when trees are cut down CO2 (carbon dioxide) is released out into the atmosphere as carbon stored during photosynthesis is released when they are felled; secondly when the trees are cut down it means the trees no longer trap carbon through photosynthesis again leading to increased carbon within the atmosphere increasing the potential effect of warming (Union of Concerned Scientists (UCSUSA), 2008). Major countries such as Canada, Brazil, Russia, China, Indonesia, The Democratic Republic of Congo, The US and the UK have all agreed to sign the pledge and with these countries alone this covers 85% of the world’s forests (Rannard and Gillett, 2021). However, (Harvey, 2022) reports that deforestation in the Amazon alone has soared to new record levels. In the Democratic Republic Of Congo where one of our most important rainforests lie, governments willingness to stop logging and deforestation is very much in doubt (Harvey, 2022). Gibbs et al. (2020), (Global Forest Watch, 2022) and (Food and Agriculture Orgainsation (FAO), 2020) highlight that the world is a long way off completely stopping deforestation with Global Forest Watch (2022) even indicating an increase of 41% annually of tropical primary forest loss. Last year alone, nearly one-third of 350 major companies who’s supply chain production contributes to deforestation did not report of any contribution or activities in order to reduce this deforestation (Gibbs et al., 2020). Marsh (2022) reiterates the point that achieving net zero will not be possible unless we end deforestation as these trees are our biggest and most natural form of carbon sink. However, like most agreements this is also failing to be fulfilled and therefore further deterrents our net-zero and 1.5oC goal.

3. Accelerating Switch to Electric Vehicles

According to Ritchie and Roser (2020) 16.2% of our emissions comes from transport emissions with 11.9% of these coming from road transport. Leaders at COP signed an agreement for the transition to 100% zero emission sales of new cars and vans by 2040 globally and by 2030 in leading markets (Hernandez, 2021). Again like the other agreements mentioned above countries such as US, China, Germany, South Korea and Japan had not agreed to the pledges along with Toyota and Volkswagen two major car manufacturers (Hernandez, 2021). In comparison to other agreements however much more changes have been made here with the sales of electric cars alone hitting 6.6 million in 2021 (tripling the marker from 2019) (Paoli and Gul, 2022). However, this change is again pushed out with figure 2 below showing the years in which certain countries aim to end the sale of petrol and diesel vehicles. Schwanen (2019) also highlights issues around the uptake of electric vehicles such as the limited choice, the technology and the high prices for the vehicles which is contributing to the delay in change. Harvey (2022) mentions that the Ukraine-Russian war is causing disruptions for supply chains for these electric vehicles. Harvey (2022) reports that Volkswagen in Germany has already sold out of electric vehicles in the UK and US this year as a result of supply chain shortages and manufacturers struggling to keep up with the rising costs of parts. Even though its seems like a great solution one of must question this agreement in terms of emission trade-offs. Even though emissions will decrease in the transport sector the rise in electric vehicles is only going to bring an increase in energy emissions with the increased use of electricity. Even though there has been developments in the renewable energy sector, there is still not enough to provide the whole world with clean energy (Centre for Climate and Energy Solutions (C2ES), 2022). One must also question the cost of this for the consumer especially for those consumers who can barely afford cars now in both the developed and developing world and whether they will be able to afford the switch, and if not what will the consequences be ?

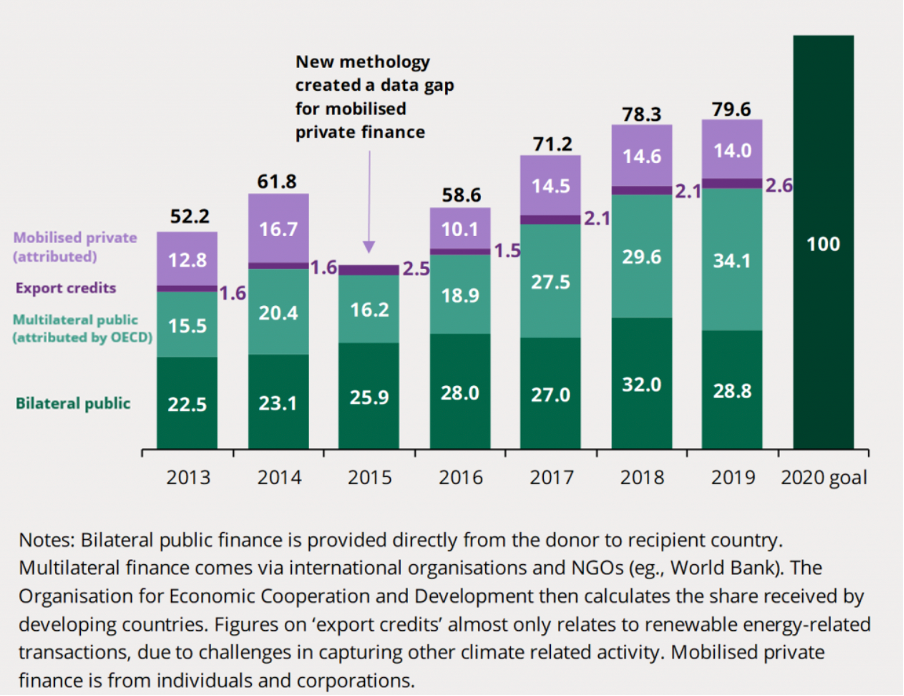

- Climate Finance

One of the most important targets or goals agreed upon was the commitment of $100 billion of climate finance every year to the developing world from the developed world however, there is huge doubt over the overall capability to do this (Area and Loft, 2021). This money is being generated by Annex 1 countries or developed countries for non-Annex 1 countries or developing countries in order to aid them in their adaptation and mitigation and to defend the most vulnerable from climate change as they are set to be hit the hardest by its impacts (Area and Loft, 2021). . However, since 2013 as seen in figure 3 below this goal has not been met hence the reason why people are questioning whether this is a feasible goal. Harvey (2022) reports that since COP26 there has been very few developments in climate finance. Therefore we must question as to whether this is feasible for the Annex-1 countries especially with the increased costs occurring as a result of the Ukrainian Russian war (Josephs, 2022). However, if this money is continually unsuccessful leaders will have to go back to the drawing board to order to generate this climate finance in order to support developing and vulnerable countries in adaptation and mitigation in the future.

Overall, 10 months on we can see that there has been very little progress made in terms of what was agreed and pledged at COP26. This would make people question whether this conference was a genuine chance for us to make a change in order to reduce emissions and work towards net-zero in the hope of tackling the climate crisis or was it just a ‘tick the box’ conference for leaders which makes them seem like they are taking climate action seriously. If we continually fail to meet the pledges we agreed to work towards net-zero we will unfortunately see detrimental and irreversible environmental consequences.

Bibliography

AREA, E. & LOFT, P. 2021. COP26: Delivering on $100 Billion Climate Finance [Online]. UK Parliament. Available: https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/cop26-delivering-on-100-billion-climate-finance/[Accessed 28/08/2022].

BBC & INTERNATIONAL ENERGY AGENCY (IEA). 2019. Briefing Energy [Online]. BBC. Available: https://news.files.bbci.co.uk/include/newsspec/pdfs/bbc-briefing-energy-newsspec-25305-v1.pdf[Accessed 29/08/2022].

CARVER, D. 2022. What were the Outcomes of COP26? [Online]. UK Parliament. Available: https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/what-were-the-outcomes-of-cop26/ [Accessed 28/08/2022].

CENTRE FOR CLIMATE AND ENERGY SOLUTIONS (C2ES). 2022. Renewable Energy [Online]. Center for Climate and Energy Solutions. Available: https://www.c2es.org/content/renewable-energy/ [Accessed 29/08/2022].

CENTRE FOR RESEARCH ON ENERGY AND CLEAN AIR (CREA) 2022. Powering Down Coal- COP26’s Impact on the Global Coal Power Fleet.

FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGAINSATION (FAO) 2020. Global Forest Resources Assessment 2020.

GIBBS, D., HARRIS, N. & REYTAR, K. 2020. Progress Must Speed Up to Protect and Restore Forests by 2030 [Online]. World Resources Institute (WRI). Available: https://www.wri.org/insights/progress-must-speed-protect-and-restore-forests-2030 [Accessed 28/08/2022].

GLOBAL FOREST WATCH 2022. Global Forest Watch Data. In: WATCH, G. F. (ed.).

HARVEY, F. 2022. ‘Cash, Coal, Cars and Trees’: What Progress has been made since COP26? [Online]. The Guardian. Available: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2022/may/14/cash-coal-cars-and-trees-what-progress-has-been-made-since-cop26 [Accessed 28/08/2022].

HERNANDEZ, J. 2021. COP26 sees Pledges to Transition to Electric Vehicles, But Key Countries are Mum [Online]. NPR. Available: https://www.npr.org/2021/11/10/1054256978/cop26-agreement-electric-vehicles-auto-industry?t=1661713264419 [Accessed 28/08/2022].

HOOG, N. D. & KIRK, A. 2021. Current Coal Phaseout Pledges ‘Absolutely Not Enough’, Warn Experts [Online]. The Guardian. Available: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/ng-interactive/2021/dec/23/why-cop26-coal-power-pledges-dont-go-far-enough-visualised [Accessed 28/08/2022].

JOSEPHS, J. 2022. Ukraine War to Cause Biggest Price Shock in 50 Years- World Bank [Online]. BBC. Available: https://www.bbc.com/news/business-61235528 [Accessed 29/08/2022].

MARSH, A. 2022. Net-Zero Targets Aren’t Attainable Without Ending Deforestation [Online]. Bloomberg. Available: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-06-28/net-zero-targets-aren-t-attainable-without-ending-deforestation [Accessed 28/08/2022].

MYLLYVIRTA, L. 2021. Most Countries are Making Progress on Phasing Out Coal- But Not Fast Enough to Offset China’s Expansion [Online]. CREA. Available: https://energyandcleanair.org/most-countries-are-making-progress-on-phasing-out-coal/ [Accessed 28/08/2022].

PAOLI, L. & GUL, T. 2022. Electric Cars Fend off Supply Challanges to More than Double Global Sales [Online]. IEA. Available: https://www.iea.org/commentaries/electric-cars-fend-off-supply-challenges-to-more-than-double-global-sales [Accessed 28/08/2022].

PARRA, P., GANTI, G., BRECHA, R., HARE, B., SCHAEFFER, M. & FUENTES, U. 2019. Global and regional coal phase-out requirements of the Paris agreement: insights from the IPCC special report on 1.5 C climate analytics [Report]. Climate Analytics, 34 pp.

RANNARD, G. & GILLETT, F. 2021. COP26: World leaders Promise to End Deforestation by 2030 [Online]. BBC. Available: https://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-59088498 [Accessed 28/08/2022].

RITCHIE, H. & ROSER, M. 2020. Environmental Impacts of Food Production [Online]. OurWorldInData.org. Available: https://ourworldindata.org/environmental-impacts-of-food#citation [Accessed 24/08/2022].

SCHWANEN, T. 2019. The Five Major Challanges Facing Electric Vehicles [Online]. BBC. Available: https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-49578790 [Accessed 28/08/2022].

UNION OF CONCERNED SCIENTISTS (UCSUSA). 2008. Tropical Deforestation and Global Warming [Online]. UCSUSA. Available: https://www.ucsusa.org/resources/tropical-deforestation-and-global-warming [Accessed 28/08/2022].

UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD. 2022. What is Net Zero? [Online]. Available: https://netzeroclimate.org/what-is-net-zero/ [Accessed 29/08/2022].

WANG, P., YANG, M., MAMARIL, K., SHI, X., CHENG, B. & ZHAO, D. 2021. Explaining the slow progress of coal phase-out: The case of Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Region. Energy Policy, 155,112331.