One of the biggest and most profitable sectors within Irish agriculture today is the dairy sector with over 18,000 dairy farmers and over 1.55 million dairy cows (Teagasc, 2022; Smyth, 2021). Ireland's temperate climate creates ideal conditions for grass growth which is fed to dairy cattle all year round usually in the form of silage or fresh pasture grass, one of the factors contributing to the sectors profitability (Teagasc, 2022; Smyth, 2021). In recent years this sector has been growing with data from the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) showing a 3.2% increase in 2020 alone in the number of dairy cows on farms. The 2020 rise was the 10th consecutive year of an increase in the number of dairy cows on Irish farms, with (Irish Farmers Association (IFA), 2020) stating that in the past 5 years there has seen an increase of 400,000 cows in Ireland (IFA, 2020; Smyth, 2021)

However, even though this sector generates huge amounts of income for a large proportion of the Irish population and economy this sector does come with a huge environmental price with its contribution to greenhouse gases (GHGs) and climate change (EPA, 2022). This Irish agricultural sector alone in 2020 was responsible for 37.1% of all GHG's produced in Ireland with it contributing to GHG's such as carbon dioxide (CO2), nitrous oxide (N2O) and most importantly in terms of climate change and the dairy sector, methane (CH4) (Smyth, 2021; EPA, 2022).

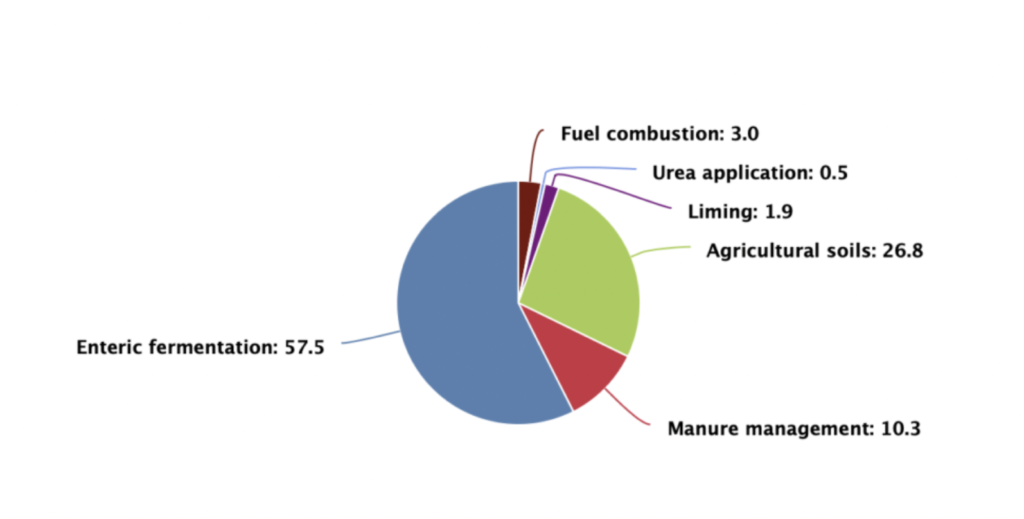

From Figure 1 below we can see the sources of GHG's in Irish agriculture in 2020 with enteric fermentation coming out as the leading contributor which is very important in terms of dairying in Ireland and climate change (EPA, 2022). Enteric fermentation is a natural process in ruminants where bacteria breaks down organic matter producing hydrogen (H), carbon dioxide (CO2) and methane (CH4) (Food and Agricultural Organisation (FAO), 2022). In the fore-stomach of the rumen microbial fermentation breaks down food into soluble products that is used by the animal (Gibbs and Leng, 1993; USEPA, 1995). This microbial fermentation that occurs in the fore-stomach enables the rumen to digest rough and coarse plant material. The by-products of this microbial fermentation are H, CO2 and CH4 which are later excreted (Gibbs and Leng, 1993; USEPA, 1995). The methane produced from this process and methane coming from the 10.3% of GHGs produced by manure management is very important in terms of Ireland's GHG emissions. Methane is a very potent GHG, with it being 25 times greater than CO2 over a 100 year period (Solomon et al., 2007). However, even though the gas is much more potent it only has an atmospheric lifespan of 10-12 years (Solomon et al., 2007), leaving it as our best chance to reduce GHG emissions in a shorter space of time.

Most of the N2O emissions produced globally are coming from agricultural soils and an increased use of fertilisers and manure inputs (Mosier et al., 1998; Reay et al., 2012). With the increasing herd growth in recent years however, there has been an extra pressure to grow more grass encouraging more fertiliser use in Ireland and contributing to the 26.8% of agricultural soils emissions seen in Figure 1 below.

Finally, global CO2, emissions from agriculture stem from deforestation and land use change (FAO, 2021). But, in Ireland this isn't as big a problem as it is in other regions around the world. Instead a lot of the CO2 in Ireland comes from lime and urea application (2.4% in Figure 1 below). Other CO2 emissions in agriculture in Ireland also come indirectly from fuel combustion (3.0% in Figure 1 below).

However, in terms of the Irish dairy sector the first question we need to ask is what can be done to reduce and mitigate emissions especially methane emissions in order to have a big impact on climate change and emissions both nationally and globally. The second question we need to ask is are the ideas that are suggested for mitigation actually realistic and achievable for the Irish dairy system and farmer or are they just more dreams that people hope works ? Finally, we also need to ask as to whether the dairy farmer is being included in talk or discussions around dairy farming in Ireland and reducing the sectors emissions.

There has been numerous suggestions to try and mitigate or even reduce emissions from the dairy sector. As discussed above the biggest GHG coming from the dairy sector is methane. Emmet-Booth et al., (2019) suggested methods such as extending the grazing season and improving genetic efficiency of dairy livestock in order to reduce GHG emissions.

Extending the grazing system for dairy cattle means that they will consume less lignin or cellulose as they will be spending more time out on fresh pasture rather than consuming conserved grass such as silage which is high in both lignin and cellulose, which is associated with higher levels of methane emissions (Emmet-Booth et al., 2019; Boadi et al., 2004). With cows consuming more outdoor fresh pasture it will see a reduction in livestock housing periods which in turn reduces the amount of manure which needs to be stored and therefore reduces methane emissions associated with the storage (Emmet-Booth et al., 2019). In terms of sustainability this idea works however, coming from a dairy farm myself one must question as to whether this will be viable for all farmers across Ireland. Ireland's climate can be very changeable and it can leave runways and fields in a hard to manage state and keeping cattle on it for longer could in fact cause more damage to the field. It's also important to note that bad conditions on foot for cows can actually injure cows badly and leave them unable to walk and no longer viable within the farms system. Finally, one must also question as to whether sufficient grass is available all year round for dairy cattle in Ireland with again weather conditions being so changeable especially in winter months (Reidy, 2016).

Genetic efficiency has improved drastically is the past 2 decades and is still developing in terms of reducing the dairy industries impact on climate change. Breeding indices such as the dairy Economic Breeding Index (EBI) can be used to choose genetic traits (for example, feed intake, methane emissions, daily live weight gain and animal health) in dairy cattle associated with reduced GHG emissions and improved production efficiency. EBI has a huge capacity to improve such traits. Cattle which have a higher EBI are more fertile reducing the farms replacement rate and calving unit therefore reducing methane emissions produced per unit of product. EBI also brings other benefits such as increased milk yield and composition, improving efficiency of production and decreasing emissions per unit of product. EBI has also brought an improved health status on farms with it reducing the incidence of disease, leading to higher production levels and lower replacement rates and overall lowering GHG emissions. Finally EBI has influenced feed intake of cows and therefore cows methane excretion. A smaller cow consumes less feed than a larger one therefore small cow traits are used in DNA which can produce a more sustainable cow breed that produces high yields (McDonnell, 2021). Breeding schemes such as that of EBI are a good way of developing more environmentally efficient livestock however, sometimes we must also note that this option is not always financially viable for some farmers (McDonnel, 2021) and therefore highlights the need to include farmers in designing schemes such as this in order to make it viable and successful for all.

With strategies and ideas like these being developed and implemented it is clear that plans like these are definitely not viable for all farmers. When developing ideas and plans such as those above one must question as to whether farmers from all types of dairy farms are being included in talks and discussions in relation to these ideas. From the outside looking in the plan looks great and seems like not implementing such strategies would be a mistake however, when you delve in and start to look at issues arising from such ideas you have to wonder whether these plans are viable for all and who was included in talks and discussions when these strategies were being formulated.

When looking at these mitigation strategies one must also ask as to whether farmers are actually aware of them. A survey carried out by Drennan, (Not Dated) examined the attitudes of dairy farmers in relation to the reduction of GHG emissions like methane. Findings from the survey showed that famers ‟ in general had a good understanding, awareness and willingness to adapt to mitigation strategies‟ to reduce GHG emissions. The findings also showed that farmers ‟ understanding of the impact of GHG emissions was quite good and there was a general acceptance that the dairy farming industry should contribute in helping to lower agricultural emissions". However, farmers did mention that awareness levels could be improved in relation to the implementation of such mitigation strategies such as those discussed above. Farmers surveyed also felt that in order to increase the uptake of such strategies "a high level of knowledge transfer is required showing credible and thoroughly tested results which have been carried out on comparable farms" (Drennan, Not Dated).

I think to encourage and see an uptake of schemes such as those mentioned above scientists, government parties, organisations along with other environmental and agricultural organisations and societies need to first provide knowledge regarding such schemes to all farmers across Ireland. To further encourage uptake some form of financial incentive should also be given whether it be funding towards installation or capital costs or funding in the form or grants or yearly/monthly payments. Overall, those who know best about these ideas and schemes must promote and incentivise such ideas in order to increase the uptake and see a reduction in the dairy sectors GHGs.

In conclusion it is undeniable that the Irish dairy industry is contributing to Ireland's GHG emissions. Research shows that there are ways to reduce these emissions however, they do come with their drawbacks which allows one to question as to whether farmers are being considered in discussions, talks and knowledge sharing of such schemes. Finally, such schemes need to be promoted by scientists, governments, agricultural and environmental organisations across Ireland through knowledge sharing and financial incentivisation.

Bibliogrphy

BOADI, D., BENCHAAR, C., CHIQUETTE, J. & MASSÉ, D. 2004. Mitigation strategies to reduce enteric methane emissions from dairy cows: Update review. Canadian Journal of Animal Science, 84, 319-335.

DRENNAN, A. Not Dated. Dairy Farmers’ Attitudes to Reducing Methane Emissions through Changes in the Diets of Dairy Cows [Online]. Teagasc. Available: https://www.teagasc.ie/media/website/publications/2020/Abstract-Aoife-Drennan.pdf [Accessed 28/03/2022].

EMMET-BOOTH, J. P., DEKKER, S. & O’BRIEN, P. 2019. Climate Change Mitigation and the Irish Agriculture and Land Use Sector. Working Paper on Climate Change Advisory Council: Dublin, Ireland.

ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AGENCY (EPA). 2022. Greenhouse Gas Emissions (GHG)- Agriculture [Online]. EPA. Available: https://www.epa.ie/our-services/monitoring--assessment/climate-change/ghg/agriculture/ [Accessed 28/03/2022].

FAO 2021. Emissions due to agriculture. Global, regional and country trends 2000–2018. FAOSTAT Analytical Brief Series No 18.

FOOD AND AGRICULTURAL ORGANISATION (FAO). 2022. Reduciing Enteric Methane for Improving Food Security and Livelioods- What is Enteric Methane? [Online]. FAO. Available: https://www.fao.org/in-action/enteric-methane/background/what-is-enteric-methane/en/ [Accessed 28/03/2022].

GIBBS, M. & LENG, R. Methane emissions from livestock. Proceedings of the International Workshop on Methane and Nitrous Oxide. Methods for National Inventories and Options for Control. RIVM report, 1993. 73-79.

IRISH FARMERS ASSOCIATION (IFA). 2020. Dairy Fact Sheet [Online]. IFA. Available: https://www.ifa.ie/dairy-factsheet/ [Accessed 28/03/2022].

MCDONNELL, B. 2021. Reducing Emissions from your Dairy Herd through EBI [Online]. Agriland.ie. Available: https://www.agriland.ie/farming-news/reducing-emissions-from-your-dairy-herd-through-ebi/ [Accessed 28/03/2022].

MOSIER, A., KROEZE, C., NEVISON, C., OENEMA, O., SEITZINGER, S. & VAN CLEEMPUT, O. 1998. Closing the global N2O budget: nitrous oxide emissions through the agricultural nitrogen cycle. Nutrient cycling in Agroecosystems, 52, 225-248.

REAY, D., DAVIDSON, E., SMITH, K., SMITH, P., MELILLO, J., DENTENER, F. & CRUTZEN, P. 2012. Global agriculture and nitrous oxide emissions. Nature Climate Change, 2, 410-416.

REIDY, B. 2016. Pros and Cons of this Year’s Extended Grazing Bonus [Online]. Irish Examiner. Available: https://www.irishexaminer.com/farming/arid-20431001.html [Accessed 25/08/2022].

SMYTH, O. 2021. Farming- A Big Problem for Ireland’s Climate Goals? [Online]. RTE. Available: https://www.rte.ie/news/primetime/2021/1026/1256029-farming-dairy-climate-change/ [Accessed 28/03/2022].

SOLOMON, S., QIN, D., MANNING, M., CHEN, Z., MARQUIS, M., AVERYT, K., TIGNOR, M. & MILLER, H. L. 2007. IPCC, 2007: Climate change 2007: The physical science basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the fourth assessment report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. SD Solomon (Ed.).

TEAGASC. 2022. Dairy [Online]. Teagasc. Available: https://www.teagasc.ie/animals/dairy/ [Accessed 28/03/2022].