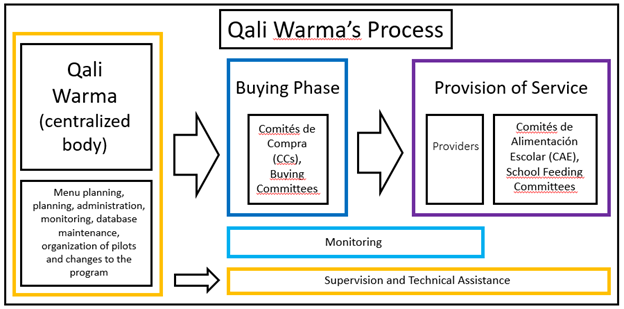

Last Friday, I was able to meet with the Chief of Performance of Qali Warma; this was my first opportunity to speak to someone in the program. Our conversation covered a lot of ground and helped me to feel out the position of Qali Warma. When I asked about the possibilities of including more diversity in the menus, I was told that Qali Warma has a couple of initiatives to include traditional potato varieties in Junin and tarwi in Ancash. This was news to me, so after a Google search I was able to discover the scale of the programs.

Tarwi is a traditional Andean food most commonly found in Peru and Bolivia; those familiar with flowers will recognize that tarwi is part of the lupine family. Here, the beans are eaten as an accompaniment to a meal, in ceviche (marinated in lemon juice and hot pepper), or served in a dish such as tarwi with potatoes and rice.

Qali Warma is bringing tarwi in the form of bread to six provinces of the department of Ancash, reaching 76,500 students. The tarwi is ground into flour or boiled and mashed before getting mixed into the dough.

The second initiative is taking place in department of Junin; SENASA (the Peruvian agency that monitors agriculture and provides technical support) and the regional agriculture board of Ica have provided trainings and technical support to farmers. Farmers have formed cooperatives so that they can produce potatoes not just of sufficient quality but also sufficient quantity for the demand.

This collaboration and hard work has resulted in 336 schools in four provinces with a total of 17,352 students receiving traditional varieties of potatoes in their school meals. The estimated amount bought for 2019 is 31 tons.

Qali Warma faces a number of troubling challenges, and as with any large bureaucracy, moves slowly. However, these initiatives and their pilot programs show that there are some in the institution who wish to make positive changes; the success of these initiatives can be scaled out to more regions in Peru. While neither of these initiatives will completely change how Qali Warma functions, they do show how the model can be flexible enough to include some kinds of non-perishable foods without endangering food safety, or bogging down the administration to a prohibitive degree.