The history behind locally sourced school meal programs began in earnest in 2009 when Brazil launched its Programa Nacional de Alimentação Escolar (PNAE).

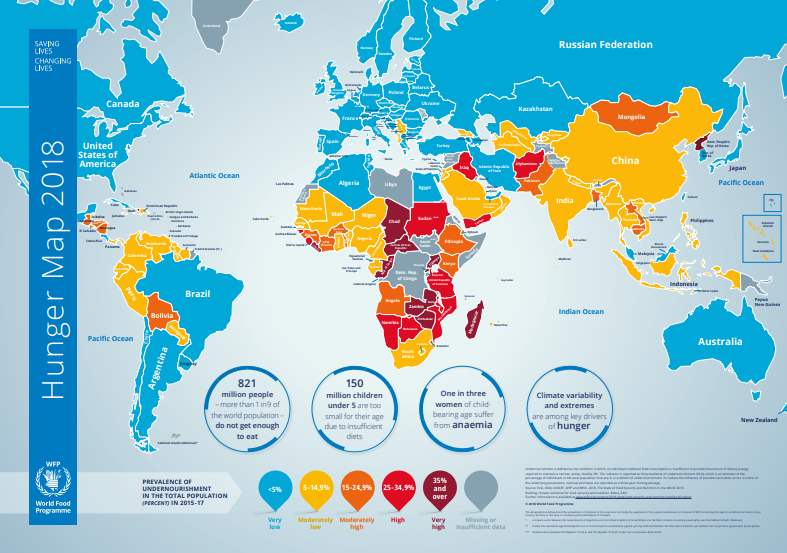

Generally speaking, when we think of Brazil we think about Carnival or impressive amounts of corruption (think Odebrecht); we might even worry about the nationalistic turn the country has taken. But Brazil has - somewhat quietly - sounded out a resounding victory against hunger, enacting coordinated policies designed to feed Brazilians under the umbrella of Fome Zero (Zero Hunger), an intersectorial push that removed Brazil from the World Food Program's Hunger Map in 2014.

One of their first programs began in 2003, the Programa de Aquisição de Alimentos (PAA), which buys food for public institutions; family farmers and agroecologial practices are encouraged, with the end of strengthening the Brazilian economy and providing food autonomy.

PNAE began a few years later; municipalities establish relationships with farmers and other suppliers and buy food for their schools. (This is a drastically different system to Peru, where menus are decided on a national level and purchases are made according to a strict list of allowed products on a regional level.) Brazilian municipalities are aided by nutritionists to ensure that the meals provided are nutritionally adequate; deliveries are made at the schools, where the people in charge of receiving food check for quality and quantity requirements.

There is a minimum of thirty percent of the food purchases to be made locally, which some of the municipalities are exceeding. PNAE is often sourced from framers with smaller plots of land that produce for local markets (rather than export markets for crops such as corn and soy).

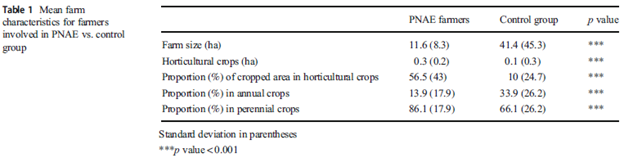

Valencia et al (2019) shows the dynamics between farmers who supply PNAE and those who do not:

However, this is not an accurate picture of the entire country; these results are from the state of Santa Catalina, which has a highly developed and diverse agricultural mosaic. Other states have not had the same success, and there are reports of municipalities buying no local food in their PNAE programs - in 2014, 3345 of the 5534 municipalities (60 percent) did not reach the 30 percent minimum of local products; 23 percent did not buy locally at all (Hunter et al 2016). This may be because there is a lack of political will or because the agricultural system in the area is not able to provide both for the usual needs of the community and the needs of PNAE, making external sourcing necessary.

The wide-scale support of the program across sectors has garnered international attention and has been responsible for the inspiration behind the school meal programs in dozens of countries in Africa and the Americas, including but definitely not limited to: Nicaragua, El Salvador, Ethiopia, Ghana, Kenya, Malawi, Nigeria, Tanzania, and Mali.

Groundbreaking public acquisition programs may not be what Brazil is known for on the street, but it is worthy of attention as a model of what is possible, a model that can be changed to fit the conditions of highly varied countries the world over.