I was in Peace Corps in Peru for about a year and a half; I was placed in the small town of Capilla Central in the district of Olmos in the department of Lambayeque. I was there for a little over a year, and grew to love the place and the people who lived there. Naturally, since I'm in Peru there was no way that I could come to the country without visiting Capilla, so that's where I went last weekend.

A great many things remained the same - including the warm welcome I received - but there were a few changes, such as the huge new park, still establishing its seedlings:

Also new were the changes made to the dry riverbed since the 2017 El Niño: the Department of Transportation has lumped up a bunch of the sand into a long hill. I'm not sure what this serves, aside from ensuring that the river channel is deep enough for the deluge of water in the next fenómeno. (Seems to me that it makes more sense to truck away the sand so that it doesn't clog anything up downriver, but that's probably prohibitively expensive.)

I mainly spent my time trying to ensure that I caught up with as many people as possible, handing out maple candies from Maine, gossiping like mad, and enjoying the slower pace of life out in the country.

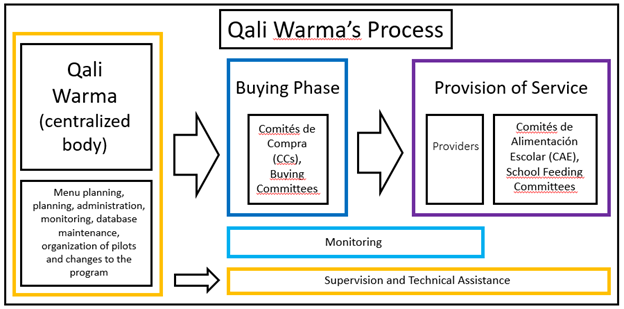

However, because I stayed from Saturday afternoon to Monday afternoon, I was invited to see what Qali Warma looks like in Capilla. On Saturday, Nelly and Fanny were putting away the recent shipment of food they had received for the month, and talked to me about their experiences with Qali Warma.

This opportunity gave me the answer to one of the mysteries plaguing me during my research: what, exactly, is a 'galleta'? Galleta in Spanish can translate to any number of things: cookie, cracker, biscuit. I've been using 'biscuit' in my thesis as it is ambiguous - they can be either sweet or savory. Nelly and Fanny showed me that the galletas they receive can be either, and that it depends on the rotation of things that Qali Warma send them. (And, of course, the kids like the sweet ones better - go figure.)

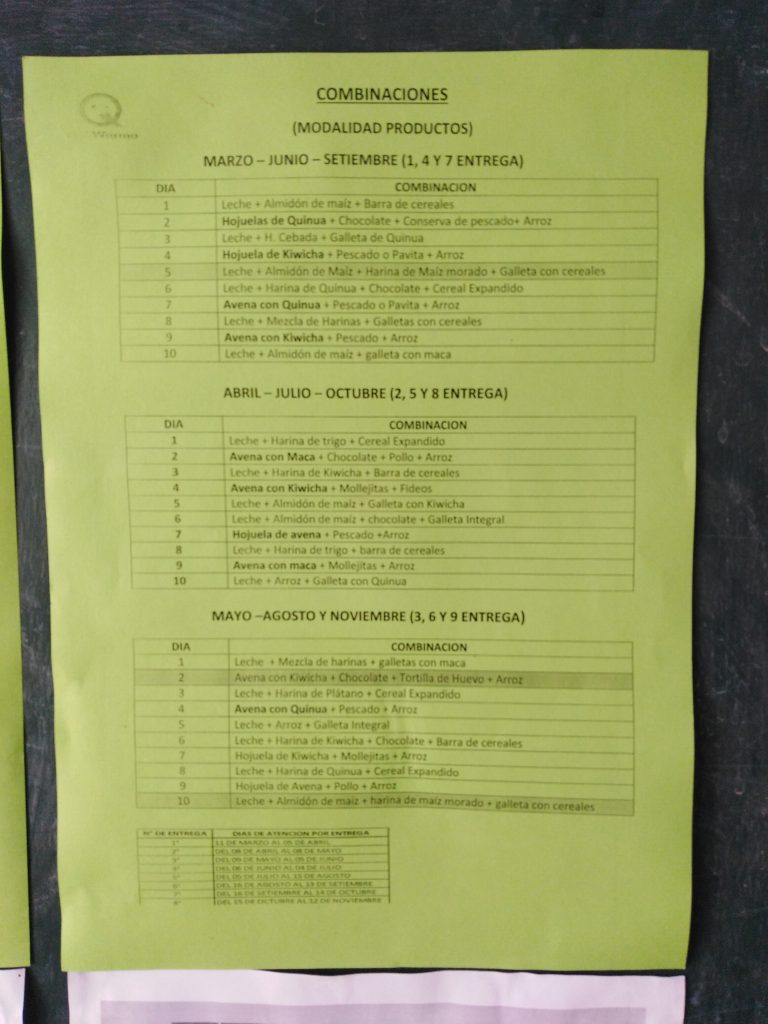

This 'rotation' is something new this year: so the kids don't get crazy bored with the school meals, the deliveries are on a three month rotation. There's something different for each month for three months, after which point the cycle restarts. This is something that the Buying Committee gets to decide; they stay within the regulations of Qali Warma but provide what variation they can.

The cook arrives at the school around seven a.m. to start cooking the breakfast, and serves breakfast from around 7:45 to 8:30, depending on when the kids arrive. There's a dedicated place for the children to eat (which not all schools have), though considering that some kids arrived late, they had to eat their breakfast in the classroom.

On Monday, the menu was milk with cornstarch, sugar, and vanilla with a cracker that had either quinoa or maca in it. I was given a portion, and can tell you that the milk was very sweet, slightly thickened from the cornstarch, and had a nice vanilla taste; most of the kids drank all of theirs. The crackers...those mostly went into pockets. I was told that a lot of the kids don't eat the crackers given to them, instead pocketing them and giving them to their family or to pigs or dogs.

On days when there's a rice or noodle dish with some protein in it, kids may or may not eat that as well - this is because Qali Warma doesn't give money for things like condiments or spices, so it doesn't necessarily taste great. (Though I'll also note that a couple people blamed the cook for the taste of the food - but considering what she has to work with, I think she's doing fine). The parents put together money every month (4 soles/parent, ~1 USD) to buy things such as extra ingredients - this can be more of something they run out of (they usually run out of sugar, and considering how sweet the milk was that morning, I can understand why), spices, or vegetables (usually onion) - or to refill the tanks of gas that they use for cooking.

Qali Warma gave them the stove (though the cook noted that when it was delivered, one of the burners broke, so there are only two burners working), as well as the two tanks of gas. Qali Warma doesn't repay to refill the gas, but considering the large initial investment for the tank itself, that they gave the tanks is a huge advantage.

It was also good to see some of the signage that was posted in the kitchen - numbers to call in case there was anything wrong with the food, a poster on fortified rice (which, by the way, the kids don't like because of the texture), amounts of different foods to give per kid, and details on the three-month rotation. I gawped at all of it between talking to the cook and taking sips of milk.

When I asked people what they thought about the program, there were some who figured it was just fine and those who thought it was pretty boring. I think there's consensus that they would like improvements to the program, and I don't think anyone in Qali Warma asked their opinion on the matter. I'm mainly worried about how much sugar seems to be necessary to get the kids to eat their portion of milk, and how sweet the galletas need to be to get eaten in school.

In short, my weekend was a tremendous gain for me personally (I missed Capilla even more than I thought I did), and for my thesis.