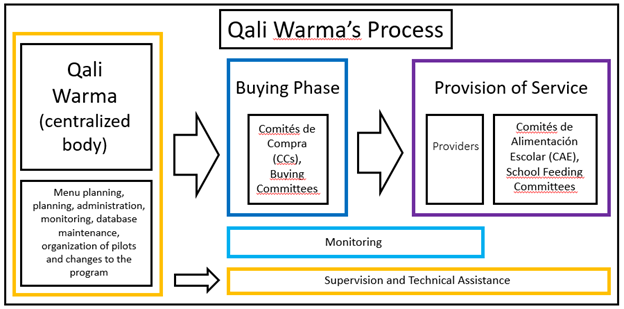

After reading a landslide of formal documents of Qali Warma, I'm able to accurately summarize how the program works:

All of the big decisions are made at the national level; the Buying Committees (CCs) buy from a list of approved foods; those providers who are given contracts are in charge of delivering food to schools, where there are committees (CAE) who are in charge of receiving, preparing, and giving the food to the children. Qali Warma supervises the process, penalizes providers who do not conform to their standards, and works with agencies such as SENASA, who monitor the quality of foods and the functioning of the value chain.

All the food provided by Qali Warma is shelf-stable (with the exception of bread and eggs). Approved foods include rice, noodles, crackers, different kinds of flour and flaked grains, milk, dried beans and lentils, cheese, olives, and canned 'products of animal origin.' This last category is a collection of strange food items (even to Peruvians - I checked with my office mates), and includes not just canned fish but also canned: chicken, beef tripe, and fish-balls in sauce. Another food in this category sounds horrible to me but is a common food here: sangrecita, chicken blood. I'm told that when it's cooked well, it tastes pretty great.

Still, I'd say sangrecita day is a good one to be a vegetarian.

There are set menus that schools follow which have restrictions on the categories of food that can be used each day; they usually have a milk drink with different grains in it or perhaps fruit juice, along with bread, rice, or noodles and a product of animal origin or legumes. Sometimes it's a drink and a cracker or a slice of cake with Andean grains in it.

Most schools follow this scheme, but there are some pilot programs that have changed how Qali Warma works, in order to add fresh produce into the school meals.

One completed and self-perpetuating pilot has taken place in Junin, a department to the east of the department of Lima. There, the FAO and the Junin Qali Warma authorities helped schools begin school gardens, enhanced the capabilities of local farmers, built a processing plant for produce, and helped organize CAEs in participating schools. This was undertaken with a broad base of support from a number of different institutions, and is still in operation after the FAO stepped back.

Here's how it works: each month, the CAEs receive money from each parent for each kid they have in school. This is somewhere around 4-5 soles per child per month, between one and two USD. They use this money to buy fresh foods to complement what they are getting from Qali Warma, and can buy from the regular local market or from the agroecological market that the FAO helped to found through farmer trainings and the processing plant. In many cases, the choice of the CAE is between buying a lot of food of uncertain safety in the normal market or buying less food of better safety in the agroecological market. After trainings, most CAEs prefer buying in the safer markets.

This pilot has produced some great effects, particularly in the level of satisfaction in the service. It does have some flaws, though, as concerns the traceability of foods: if a child gets sick as a result of the school meal, it's crucial to know where that food came from. In addition, the money for the fresh food comes from parents (and in some cases, the municipalities): Qali Warma's funding isn't contributing to this at all. Add onto that that this wouldn't work in every part of Peru, and this pilot remains the sort of thing that provides highly valuable experiences, but something that would have to be tinkered with and changed before its rollout on a national level.