One of the strategies used to inject nutrition into school meals is to incorporate local food into the menus. Local food has a different definition depending on the application - for some, 'local' meas that it comes from within the country, others withing the region, others within a specific range (for example, I worked for a store where 'local' meant a radius of 30 miles).

Local buying enables producers to secure a predictable demand for their products and can, in some cases, allow farmers to diversify what they grow: if schools demand an array of fruits and vegetables and buy that produce locally, this can change how agriculture is conducted in the area.

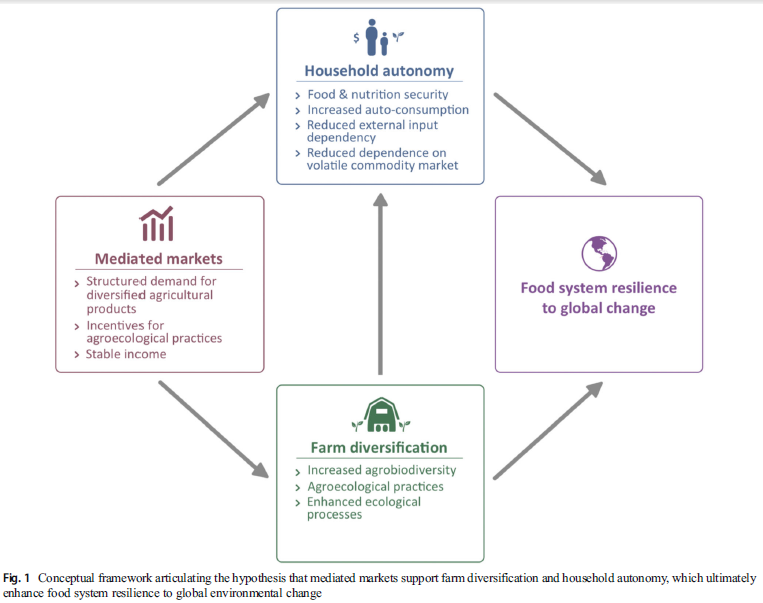

Valencia et al. (2019) drew a flow chart to describe how local buying can impact markets, households, agriculture, and resilience to climate change:

There are a great many ways to put a concept like this into effect; not only does the definition of 'local' need to be clearly defined, but the roles of different actors should also be clearly defined. What, for example, is the role of the central government? What social groups (women's groups, agricultural cooperatives) should bear some of the responsibility? Do farmers have direct contact with the schools?

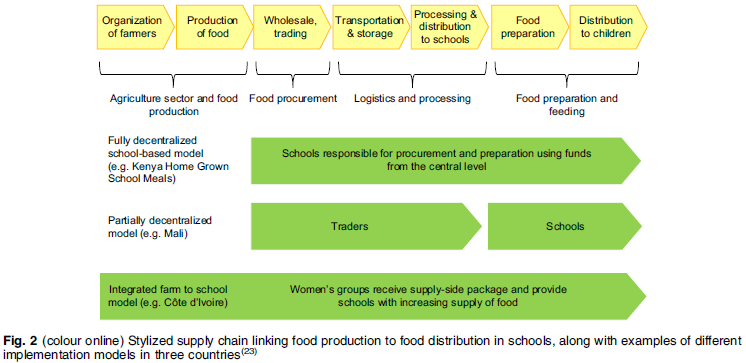

Local buying for school meals is therefore a plastic model that can be shaped to fit the unique circumstances of each country or region in which it is implemented. Bundy et al (2012) illustrates this:

This diagram shows only three out of scores of examples - and is distilled down to the most fundamental elements - but it does show the heterogeneity and flexibility in these programs.

These initiatives are challenging to implement because there are high levels of uncertainty - whether farmers can supply the demand, whether the food will be safe, et cetera - on the other hand, highly centralized programs in which food is bought from non-local sources can be brittle but have assurances as to the amount provided and the overall safety of the products.

In some cases, centralized programs work better - in places where, for example, the agriculture of the zone can only support household use - and in others, decentralized programs with local buying are better. It seems to me that most of the time, a mixture of the two works best: local buying for a portion of the food and deliveries 'from away' for the rest. As with anything, the answer isn't simple.

P.S. Lest you think that local procurement is only a feature in low-income countries, here is an example from my home state of Maine.