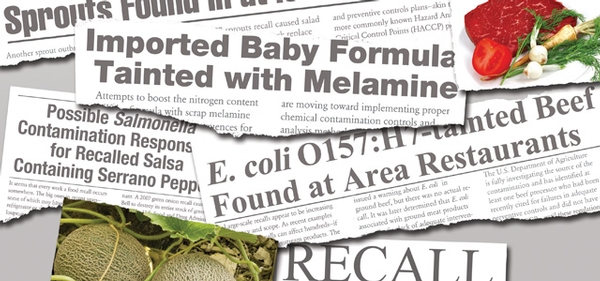

Have you ever read or heard the words “have been recalled due to…” from your news source? More than likely that’s a yes. It’s also likely that you are more familiar with the term “food fraud” than you might have previously thought.

Food fraud is defined as “illegal deception for economic gain using food which includes the US-centric subcategory of economically motivated adulteration (EMA)” (Spink et al., 2019). Fraudulent activities in food supply chains vary from global coordinated corruption to small business decisions to intentionally mislabelling products or substituting ingredients with cheaper options (e.g., pumping water into raw meat products).

Increased global vulnerability to food fraud has occurred because of phenomena such as globalisation of food supply chains, rapid food innovation driven by technological advancement, and market changes due to changing consumer choices and preferences. Recently, the Covid-19 pandemic has disrupted food supply chains and resulted in regulatory oversights which have led to concerns about potential increases in food fraud activities. The Covid-19 pandemic also further exacerbated the issue of global food insecurity which provided optimal conditions for fraudulent agents in the supply chain to perpetrate food crimes (Onyeaka et al., 2022).

To add to the complexity of battling and halting food fraud-related activities, a plethora of terms and definitions that have both overlapping and conflicting meanings include the likes of food fraud, food authenticity, food integrity, economically motivated adulteration, food protection, food crime, food security, contaminant, adulterant, amongst others (Spink et al., 2019).

Although laws, regulations, standards, certifications and best practices for food fraud prevention are evolving to best protect consumers, they are just developing. Following the aftermath of food fraud controversies that were broadcasted globally such as Sudan Red dye in ground chilli, horsemeat in beef products, diluted olive oil, melamine in powdered milks, peanut allergen in cumin, and so-called “organic” products, food fraud issues have been given more attention by governments in the United States, the United Kingdom, China and the European Union (e.g., US Food Safety Modernization Act, UK National Food Crime Unit, Chinese Food Safety Law, European Commission Food Integrity Project, ISO Technical Committee 34/Sub-Committee 17 on Food Supply Chain Management).

These regulatory and standardisation efforts are of serious importance as they can literally be the difference between life and death. More precisely, food fraud-related incidents are associated with health risks that are either direct/ immediate or indirect/chronic (Onyeaka et al., 2022).

A direct or immediate effect usually results after once-off consumption of adulterated food such as an allergic reaction to unlabelled ingredients like nuts. Whereas indirect/chronic health impacts of food fraud occur after long-term exposure or consumption of adulterated foods resulting in the build-up of adulterants within the body over time. However, another health impact of food fraud that does not receive as much attention is malnutrition as the consumers do not reap the same nutritional benefits from food products due to substitution or modification which makes essential nutrients unavailable to the consumer.

Perhaps one of the most frightening but also most intriguing aspects of food fraud is its historical prevalence. It may be a hefty current issue, but it is in fact an old issue. In ancient Rome, there were regulatory laws regarding the adulteration of wines with flavours and colours. In the United Kingdom during the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, some of the commonly used food additives were poisonous! For example, to whiten bread bakers sometimes added alum and chalk to the flour and added a pasty mixture of mashed potatoes, calcium sulphate and even sawdust to increase the weight of the finished loaves. Brewers also found themselves adding poisonous potions to supposedly improve the taste of beer after omitting a vital but pricier ingredient, hops. The practice of adulterated white bread and beer became so widespread that consumers had begun to develop a taste for adulterated foods and drinks (Shears, 2010).

Nowadays, food fraud is more sophisticated and is not just about the content of the food we are consuming. The ways that food can be fraudulent has increased, encompassing its origins, how it was produced and how it was processed. Non-product-related production and process methods hold as much value to many consumers as what they are made of (Dutfield & Suthersanen, 2022). Therefore, it will be very interesting to see what happens next within the field of food fraud. Will it be a good or bad story?

References:

Dutfield, G., & Suthersanen, U. (2022). Responding to the Global Food Fraud Crisis: What Is the Role of Intellectual Property and Trade Law?. Queen Mary Law Research Paper, (378).

Onyeaka, H., Ukwuru, M., Anumudu, C., & Anyogu, A. (2022). Food fraud in insecure times: challenges and opportunities for reducing food fraud in Africa. Trends in Food Science & Technology.

Shears, P. (2010). Food fraud–a current issue but an old problem. British Food Journal.

Spink, J., Bedard, B., Keogh, J., Moyer, D. C., Scimeca, J., & Vasan, A. (2019). International survey of food fraud and related terminology: Preliminary results and discussion. Journal of Food Science, 84(10), 2705-2718.

Spink, J., Embarek, P. B., Savelli, C. J., & Bradshaw, A. (2019). Global perspectives on food fraud: results from a WHO survey of members of the International Food Safety Authorities Network (INFOSAN). npj Science of Food, 3(1), 1-5.