As the war rumbles on in Ukraine, the Russian emphasis on food security as a domestic and international tool is not an entirely novel concept (Azarieva, Brudny, & Finkel, 2022).

Over the past 30 years, the Black Sea region has emerged as an important global supplier of grains and oilseeds, including vegetable oils. Following the collapse of the Soviet Union in the 1990s, the region was a net importer of grains. However, the high dependence on food imports was too expensive for millions and rendered the country dependent (and vulnerable) on Western food supplies. Soon after, Putin and Gordeev, the Minister for Agriculture who served from 1999 to 2009, re-ignited previously unsuccessful food security policies that would promote and regulate agricultural markets in Russia, particularly the grain industry (Dawisha, 2015). It was a win-win situation – Russia’s business community welcomed the increase in domestic supplies while serving Putin’s political goals of food independence to strengthen Russia’s sovereignty from the West.

Remarkably, from 2000 to 2018 Russia transitioned from being a net importer to becoming one of the world’s leading food exporters, which led to Russia’s 2010 official “food independence doctrine”. The food security push to secure domestic production has served Russia particularly well over the past few years (World Bank, 2020). The unprecedented food challenges that accompanied Covid-19 did not drastically alter Russia’s food supply. In fact, contrary to previous issues after the 1979 sanctions, Russia has been able to threaten “unfriendly” countries with a halt on food or energy exports as seen in recent times following the invasion of Ukraine on the 24th of February.

Before the war, Ukraine oftentimes referred to as “Europe’s Breadbasket” supplied approximately 4.5 million tonnes of agricultural produce per month through its ports, accounting for 12% of global wheat exports, 15% of its corn, and 50% of its sunflower oil. While Moscow and Kyiv signed a grain deal on July 22 to finally allow exports from three Ukrainian sea ports for 120 days, food prices have skyrocketed. The UN’s food and agricultural price index reached an all time high of almost 160 points in March before falling 1.2 in April.

Grain scarcity is deeply affecting the ability of some vulnerable food-importing countries to meet the needs of their consumers, especially in the Middle East, North Africa and the Sahel. Countries such as Egypt, Lebanon and Tunisia are heavily reliant on wheat imports particularly from Ukraine – 85%, 81% and 50% of their total wheat imports, respectively (GRID, 2020). Unfortunately, a further rise in food prices threatens to unleash an “unprecedented wave” of hunger globally – a tsunami most severely felt in developing countries where households spend a larger percentage of their income on food.

Fortunately, the brokering of the historic grain deal by the United Nations and Turkey resulted in a 10-nautical mile buffer zone that would allow cargo ships to travel safely out of ports that Russia’s military had mined. This is monumental in and of itself; however, it certainly does not lessen the pertinent issue of empty plates worldwide. If implemented successfully, the grain pact could bring down the prices of food staples in the most import-reliant countries that have seen the biggest impact of these shortages as some 20 million tonnes of last year’s harvest has been stranded in Ukraine by the war and a Russian blockade.

Another interesting point of note, the Ukrainian war is also heavily impacting the ability of international agencies to provide food aid to countries already suffering from famine or their own conflicts. For example, the World Food Programme (which purchases 50% of its grain from Ukraine) has been forced to provide reduced rations due to rising costs stemming from the concurrent energy and economic crisis and lack of available grain (Behnassi & El Haiba, 2022).

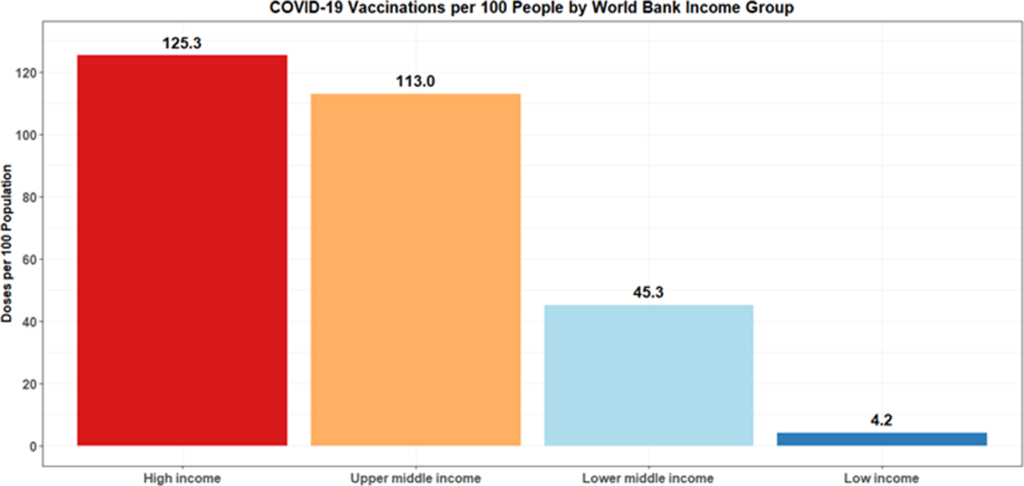

Although there are some red flags that should be heeded as these food stocks re-enter the global food supply chains. A major concern for many experts is that in a period of widespread food shortages, available supplies will end up in the hands of those with the most money and power, does this type of situation ring any bells? The distribution of the Covid-19 vaccines. The resulting upheaval could be another global health crisis, not driven by a new disease per se but by hunger. Or have we already begun out next health crisis?

The consequences felt by global food supply chains from economic, energy, climate or the Covid-19 crisis are quite similar – low supply and high prices. However, the IMF was able to predict that economies around the globe would bounce back quickly from the pandemic. As it stands, there are currently no predictions as to how long it will take for food supplies to recover to their pre-conflict state due to a large number of confounding factors that may help or hinder the situation further.

References:

Azarieva, J., Brudny, Y. M., & Finkel, E. (2022). Bread and Autocracy in Putin’s Russia. Journal of Democracy, 33(3), 100-114.

Behnassi, M., & El Haiba, M. (2022). Implications of the Russia–Ukraine war for global food security. Nature Human Behaviour, 1-2.

GRID (2020). Global food crisis: Beyond the Ukraine-Russia grain deal, what else can the world do? https://www.grid.news/story/global/2022/07/27/global-food-crisis-beyond-the-ukraine-russia-grain-deal-what-else-can-the-world-do/

Karen Dawisha, Putin’s Kleptocracy: Who Owns Russia? (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2015), 108.

Russian Federation: Agriculture Support Policies and Performance (Washington, D.C.: World Bank, 2020), 80.

Rydland, H. T., Friedman, J., Stringhini, S., Link, B. G., & Eikemo, T. A. (2022). The radically unequal distribution of Covid-19 vaccinations: a predictable yet avoidable symptom of the fundamental causes of inequality. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 9(1), 1-6.