Introduction Economic growth has traditionally been driven by the consumption of finite resources. The nature of humanity’s interaction with the planet has been take, use, and discard. Since the advent of the industrial revolution in the 19th century these behaviours have led to rapid advancements in the fields of energy, medicine, textiles, and transport to name but a few. In many corners of the world this has in turn led to increased quality of life, longer life expectancy, and relative political stability. These advances have, however, come at a cost. This ‘pursuit of happiness’ has led to a global economy willfully ignorant of the Earth’s resource limitations. The spread of wealth has been inequitable, and is worsening at a continuing rate. The traditionally wealthy regions of Europe, and North America have prospered, while many parts of Africa, the central and southern Americas, Asia and Northern Oceania have been left behind. Compounding this has been the increasing concern surrounding the ill effects of anthropogenic climate change, with these same regions expected to suffer greatly in the coming years and decades due to increased extreme weather events, the forced displacement of people, and challenges to agricultural practices. The developing countries within these regions have rightful ambitions to achieve a quality of life that Western populations have become so accustomed to. As their economies expand, so too does the pressure on the planet’s resources. In order to facilitate their growth, it is the duty of developed nations to adapt their ways of life to accommodate their fellow people. The idea of the Circular Economy has been adopted by an increasing number of nations, and big industry players as a means of facilitating sustainable growth.

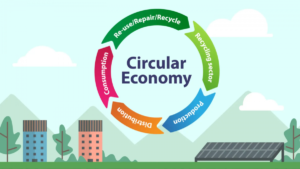

The Circular Economy The circular economy introduces the idea of cycles, and promotes their introduction as a means of mitigating the myriad effects of human-driven climate change. This circular economy looks at preventing the simple discarding of goods seemingly at the end of their life cycles. The concept minimizes waste, and closes loops in the industrial ecosystems where many of our everyday products are created. The principal idea is that many goods still have value at the point of discarding, and the circular economy aims to keep these goods and materials in the hands of those that need them and will use them. It replaces the traditional economic mantra of production to achieve profit, and introduces the idea of sufficiency and sustainability into economics. In a circular economy, we would repair what can be repaired, reuse what can be reused, recycle what can be recycled, and remanufacture what cannot be repaired, reused or recycled.

Fast Fashion The fashion sector has experienced rapid growth over the past two decades. Consumer behaviour has shifted from durable long-life products towards fast fashion, and this is having n horrific effect on the environment. The lifecycle of a trend, or range of clothing, shifts too regularly and clothes are produced on very short timeframes. Fast fashion leads to overconsumption and increased waste. Recent estimates indicate that there are 20 new garments produced for every person annually, and we are buying greater than 60% more garments than we were in the year 2000. It is estimated that the textile industry produces more than 1.2 billion tonnes of CO2 equivalent annually, and is a higher polluter than both maritime shipping and international flights. Nearly 60% of clothing produced is disposed of within 12 months, ending up incinerated or in a landfill.

How we interact with the textile industry has changed, and we now tend to throw out garments sooner than we would have done previously. One such area where there is massive waste currently is in the production and sale of children’s clothing. The fast fashion industry is booming with products aimed at this market, and parents are increasingly shifting towards buying new wardrobes for their children as they grow. An obvious solution to this issue is the rekindling of the hand-me-down culture of past decades, and the increased donation of garments no longer in use. There are entrepreneurs out there though looking at new methods of cutting down on waste through innovative clothes-swapping initiatives. One such example is Vigga Svenson, from Denmark, who wants people to start renting baby and young children’s clothes in order to cut down on fast fashion waste.Page Break

VIGGA – Clothing that grows with your child VIGGA was based upon the principles of the circular economy. Svenson’s idea was to adapt parent’s consumer patterns and intended to circulate products of a high standard that would be shared between growing families. A subscription service, VIGGA’s garments were produced under fair conditions, at a good price, and offered consumers good quality clothes for their kids. The low pricing was made possible because the clothes would be shared by several families’ children. The model was simple;

- you pay a monthly subscription fee, VIGGA deliver 20 items of clothing in your child’s size

- when the child outgrows them, you receive a new batch in the bigger size

- You return the smaller clothes, they are inspected, and washed professionally

- These clothes are then delivered to a different family, and so on.

This model provides an innovative solution to a very natural problem. It closes the cycle of constant purchasing and disposal and offers high-quality products that are also great for the environment. If such a model were to become mainstream, it would incentivize the production of higher-quality garments, thus reducing waste. Key to any business model going mainstream is of course the potential for profitability, and a higher availability of well-made, long-lasting clothing would mean more children could make use of the same items, thus reducing costs for the business. VIGGA achieved a reduction in textile waste of between 70-85% using their model. This idea is the kind of simple switch in consumer behaviour that can have the necessary transformative effect if the major polluting countries are to achieve their emissions reduction targets. We need to look at every aspect of our daily lives and see what we can alter if we’re going to do our bit to help the planet, and facilitate development in less well-off regions. This is the kind of model that could be extended to teenagers and young adults looking to freshen up their wardrobes without leaving a massive carbon footprint behind them. COVID-19 obviously represents a barrier to this inter-communal sharing, but it will be interesting to see the inroads VIGGA makes in the coming years, it could be the start of a new way of living.