Participatory research is touted as a way of completing research 'with' rather than 'about' people. In a 2013 post on the topic, Manon Koningstein mentions that, for participatory video, there are two ways it can happen:

From literature I've reviewed so far in relation to photovoice and participatory video, it seems like the first way is the most common. This raises some important considerations when thinking about true participatory research:

Selection of participants: Who researchers deem to be the appropriate stakeholders in a PAR process can influence the outcome and may not necessarily be representative of the community as a whole. This is a tricky knot to unpick as there is obviously a necessity to engage with the people in a community who are the most willing participants, and who are most likely to build on the experience to become local advocates for the positive methods developed through the PAR process. This is important to remember and reminds us that PAR methods are about Action as much as they are about Research. How to find the sweet spot where the demands of academic rigour are not completely lost to the need for energy and advocacy is something not mentioned in the literature very much.

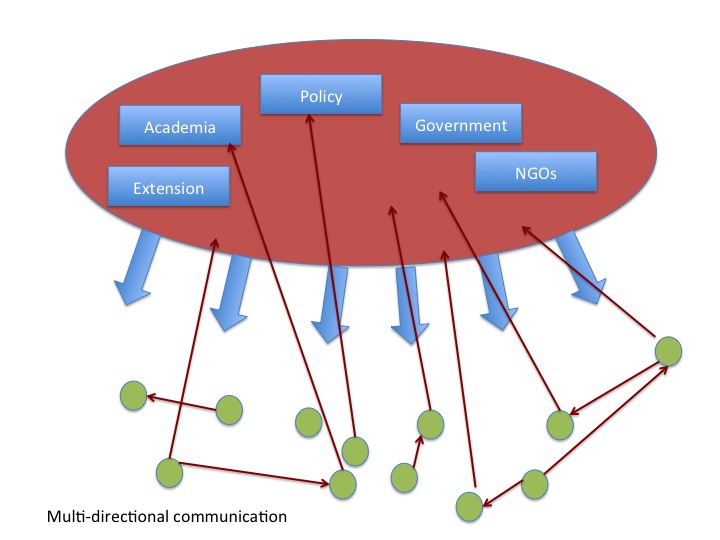

The second point I'd raise in relation to Koningstein's points above is in relation to channels of communication. If communities are to be genuine contributors to determining research directions, one-off participatory processes are only a first step. When the workshop facilitators pack up the equipment and move back to the office to assess the results, what tools and channels remain open to the community? An exhibition or a screening with policy makers is well and good but once that door is opened, it must remain so. If not, there is a danger that PAR processes become little more than tokenistic attempts at inclusion to suit the demands of researchers. If communities are momentarily empowered with the tools of photography and video, how does the removal of those tools (cameras, laptops, audience) reflect on the overall process? (Removal of cameras and IT equipment with researchers seems normal, yet what agricultural project would introduce a new tool - let's say an improved planter - teach participants the benefits and how to use it, and then take it away again?!)

When thinking about PAR, perhaps we need to reconsider the boundaries of the process such that it does not end with the exhibition and screening. In this regard, the Photovoice project run in Ma Village in Vietnam seems to be exemplary in how it has paved the way for longer term farmer led education and policy input - more info on this here.

Ian Angus' Facing the Anthropocene is well worth checking out for a concise and very readable account of the dynamics that have shaped both thinking about the Earth System and the economic and industrial forces that have brought the planet to the current crisis point.

Ian Angus' Facing the Anthropocene is well worth checking out for a concise and very readable account of the dynamics that have shaped both thinking about the Earth System and the economic and industrial forces that have brought the planet to the current crisis point.