Although, women make up nearly 50% agricultural workforce, their contribution to society and cc adaption is systematically overlooked and their voices under-represented, (FAO, 2016). Women are deemed most vulnerable of these marginalized groups due to their roles in diverse livelihood activities, their dependence on natural resources for these activities and the structural inequity in the access to and control of such resources, (Rosimo, Gonsalves, Gammelgaard, Vidallo, & Oro, 2018), (FAO, 2011), (Dankelman, 2010).

Existing literature on gender and climate change show that women and men perceive, experience and responds differently to climate change, (Villavicencio et al., 2018). Despite women’s ’’vulnerably’’, in the face of climate impacts, woman can be proactive agents of climate change adaption especially when coping with variability, long-term changes in climate and ensuring food security (FAO, 2011). FAO estimate that equal access to productive resources between male and female farmers could increase agri output in developing countries by 2.5%- 4%. However, women farmers need to break gender barriers in place by society and increase their empowerment to allow for this increased productivity. As specified by Myanmar’s 2016 NAPA, once they obtain equal access and rights, women farmers on the pathway to improved livelihoods, (FAO,2016).

CSA involves gender equality which the World Bank calls ‘’ smart economics’’ – through targeted investments and institutional reforms, CSA can help remove barriers which prohibits women from playing a full role as workers, entrepreneurs and consumers within mainstream economic life. Barriers women face in Myanmar in relation to agriculture include a range of social and cultural constraints. This type of ‘’discrimination is argued to have the dual effect of oppressing women while simultaneously depriving the economy of valuable human capital and resources, stifling aggregate growth, (Taylor, 2018). Thus, engagement via CSA aims to facilitate a simultaneous improvement of women’s welfare, gender equality and economic efficiency on local and global level. Reducing these barriers to resources, training, markets, decision making opportunities will help create equilibrize gender balance and make men and women equal partners in cc adaption and mitigation, (Villavicencio et al., 2018).

Equity, empowerment and gender relations: A literature review of special relevance for climate-smart agriculture programming. Source:https://cgspace.cgiar.org/handle/10568/98467.

As specified by Myanmar’s 2016 NAPA report, the integration of women in livelihood activities in particular farming, through the access of resources, i.e. tillage machinery, improved seed varieties, training, financial loans etc. will place them on the pathway to improved livelihood standards, (FAO, 2016).

The addition of gender to agri policy is a great step towards parity in agriculture sector where like in Myanmar, female take up large percent of the work force, yet their work and valuable contribution goes unnoticed. The recognition of the benefits gained by including gender equality and empowerment in a project is evidently growing as ‘gender and empowerment’ inclusion now regularly features as central component of international and government strategies. This further demonstrates how instrumental it is for success of development outcomes, as well ‘’a moral imperative and worthy in its own sake’’, (Alkire et al., 2013).

However, with little institutional support to back up its implementation of gender inclusive projects, is gender and empowerment are unfortunately becoming a popular buzz word due to lack of local regional national infrastructure to allow these policies to filter down. To ensure that ‘gender washing does not become affiliated with the mainstreaming gender in government policy – the inclusion of gender dimension is also vital to ensure the complexities of socioeconomic and social norms [particularly the one which act as barriers to female farmers] are understood and addressed in the design of any participatory agri project.

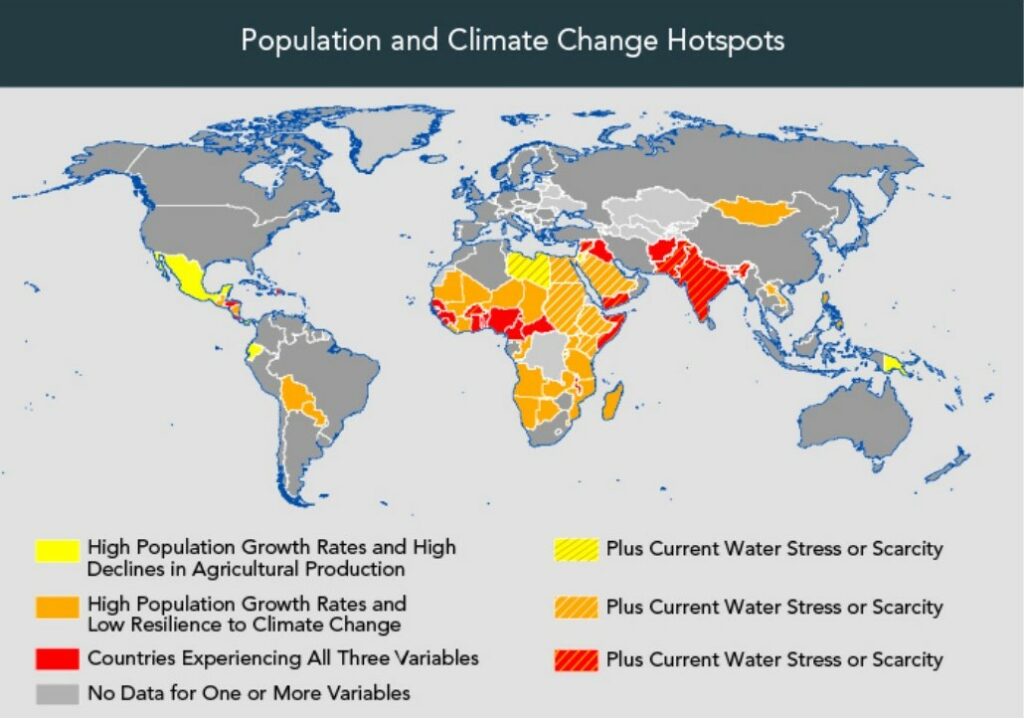

Climate change will further widen this gender gap and likely to worsen the situation for women farmers and their dependents, (Paris, 2019), as well as the food security of the country. Due to women’s dependence on natural resource they are deemed the most vulnerable to cc. another reason to ensure women’s inclusion in agri projects.

In Myanmar women traditionally have the role of buying and preparing food for their households. In country’s with similar traditional roles for women it is well documented that women, depending on household income and their access to food, largely determine the health of their household and therefore, also playing a key role in health of society. As stated in previous blog FAO estimate that equal access to productive resources between male and female farmers could increase agriculture output in developing countries by 2.5%- 4%. This creates strong reason to suggest that in Myanmar, if women’s access to reserves in agriculture was improved, could potentially improve food security and economic health of households while providing many long-term benefits for their families such as increased household income, health, education, employment, cc resilience.

To conclude, the lack of gender equality in agriculture is stifling the potential growth of the country’s economic growth and national food security. The inclusion of gender in government policies in international and government strategies may reduce the gender gap in agri, reduce women’s vulnerability to cc, increase food security, but to enable these benefits there must be support at local, regional and national level.

References:

Alkire, S., Meinzen-Dick, R., Peterman, A., Quisumbing, A., Seymour, G., & Vaz, A. (2013). The women’s empowerment in agriculture index. World development, 52, 71-91.

Rosimo, M., Gonsalves, J., Gammelgaard, J., Vidallo, R., & Oro, E. (2018). Addressing gender-based impacts of climate change: A case study of Guinayangan, Philippines.

Dankelman, I. (2010). Gender and climate change: An introduction: Routledge.

FAO. (2011). Women in Agrculture: Closing the Gender Gap for Delvelopment. The State of Food and Agriculture 2 0 1 0 – 1 1, 39-45. Retrieved from www.fao.org/3/i2050e/i2050e04.pdf

FAO. (2016). MYANMAR: National Action Plan for Agriculture (NAPA).

Paris, T. R., and M.F. Rola-Rubzen (Eds.). (2019). Gender Dimension of Climate Change Research in Agriculture

Villavicencio, F., Rosimo, M., Vidallo, R., Oro, E., & Gonsalves, J. (2018). Equity, empowerment and gender relations: A literature review of special relevance for climate-smart agriculture programming.