Climate Smart Agriculture (CSA) Awareness in Malawi

Literature reveals that, Climate Smart Agriculture (CSA) technology is a set of adaptation strategies that enable smallholder farmers to mitigate the effects of extreme weather conditions that prevail in the Sub-Saharan Africa. In their response to literature revelation of CSA technology’s mitigating effect on extreme weather conditions in the Sub-Saharan Africa, numerous stakeholders have setup plans to scale up the CSA practices among smallholder farmers in Africa. The New Partnership for Africa’s Development (NEPAD) therefore, intends to scale up CSA to at least 25 million farmers in Africa. That target by NEPAD would only be achieved by increasing the levels of awareness among smallholder farmers of the various forms of CSA practices that are available to mitigate extreme weather conditions. CSA practices have been introduced to small scale farmers in Malawi for their adoption, but the question that begs serious answers is this:

How many Climate Smart Agricultural practices do smallholder farmers of Village Savings and Loan Associations (VSLAs) groups in Malawi know?

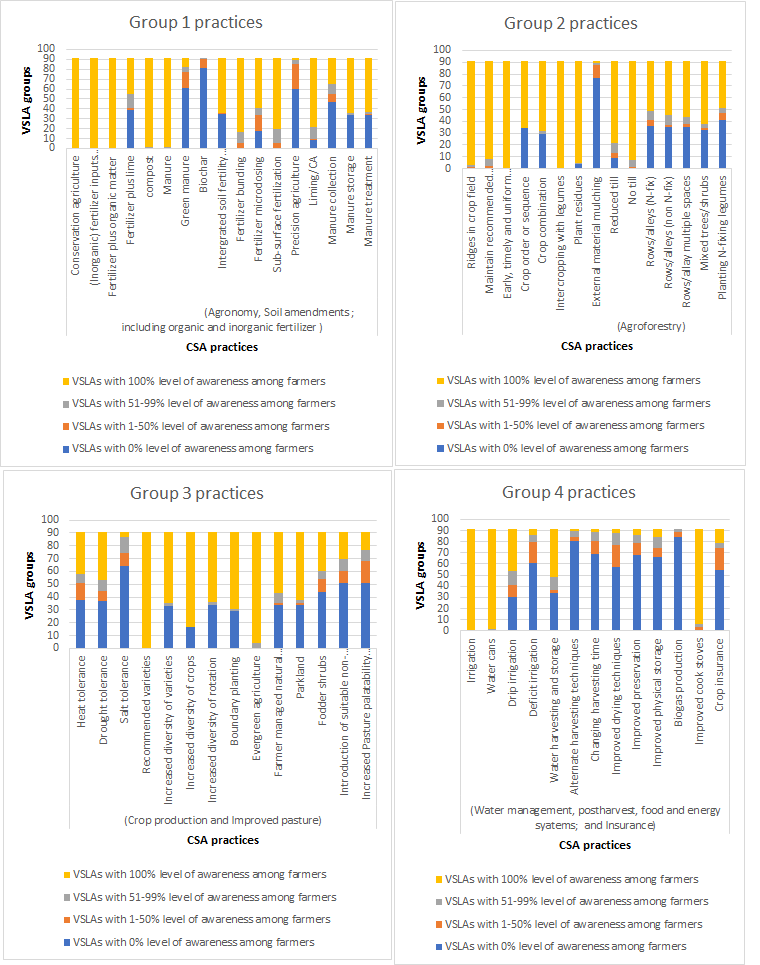

In their efforts to scale up CSA practices, the CARE Pathways project among other CSA promoters, had been promoting CSA practices among VSLA farmers of Dowa district in the Traditional Authority of Dzoole A and Dzoole B areas in Malawi. A study was conducted under the 3D4AgDev Program within National University of Ireland Galway in Dowa to explore the level of awareness of CSA practices, the adoption and dis-adoption rates among the farmers of VSLA groups. Results showed that there were high levels of awareness of various portfolio of CSA practices by the farmers (Figure 1).

A high level of awareness was noted for CSA practices that related to soil fertility and to crop production. Further, the results of the study showed low levels of awareness for post-harvest practices, rural energy and for crop insurance practices. However, it was regrettable to note that although some VSLA groups exhibited high levels of awareness for different CSA practices, there remained many other VLSA groups which were completely unaware of each CSA practice, indicating a heterogeneity of awareness of CSA practices between VSLA groups.

The observed high level of awareness that was exhibited by most VSLA groups elicited the expectation that, the extent of utilization of the CSA practices by the farmers would have been equivalent, but the study revealed the contrary was prevailing. The study revealed that, even though there was a high level of awareness of most CSA practices among some groups, the extent of use of each CSA practice was low among the VSLA groups. Further, there were some CSA practices (biochar, external material for mulching, planting N-fixing legumes, fodder shrubs, use of non-native fodders, increased pasture palatability, deficit irrigation, alternative harvesting techniques, changing harvest time, improved preservation and biogas production) that some of the VSLA farmers had knowledge of, but the farmers were completely not using them (Figure 2).

The scenario of the VSLA farmers having knowledge of CSA practices but not using them, suggests that farmers had their own priorities in terms of what to adopt. The priorities depended on which practices had immediate benefits and in other cases were less costly to the farmer. It is, therefore, cardinal for the CSA promoters to initially tailor the CSA practices to the context of the target farmers needs and / or the target farmers priorities. Use of participatory selection methods could assist promoters to choose, together with the target farmers, what CSA practices relate to farmers’ priorities and, therefore, what CSA practices to promote.

References:

CHINSEU, E., DOUGILL, A. & STRINGER, L. 2019. Why do smallholder farmers dis‐adopt conservation agriculture? Insights from Malawi. Land Degradation & Development, 30, 533-543.

KHATRI-CHHETRI, A., AGGARWAL, P. K., JOSHI, P. K. & VYAS, S. 2017. Farmers’ prioritization of climate-smart agriculture (CSA) technologies. Agricultural systems, 151, 184-191.

LIPPER, L., MCCARTHY, N., ZILBERMAN, D., ASFAW, S. & BRANCA, G. 2017. Climate smart agriculture: building resilience to climate change, Springer Nature.

ROSENSTOCK, T. S., LAMANNA, C., CHESTERMAN, S., BELL, P., ARSLAN, A., RICHARDS, M., RIOUX, J., AKINLEYE, A., CHAMPALLE, C. & CHENG, Z. 2016. The scientific basis of climate-smart agriculture: a systematic review protocol.