Dis-adoption of Climate Smart Agricultural (CSA) practices: A Less preferred option among the Village Savings and Loan Associations (VSLA) group farmers in Malawi

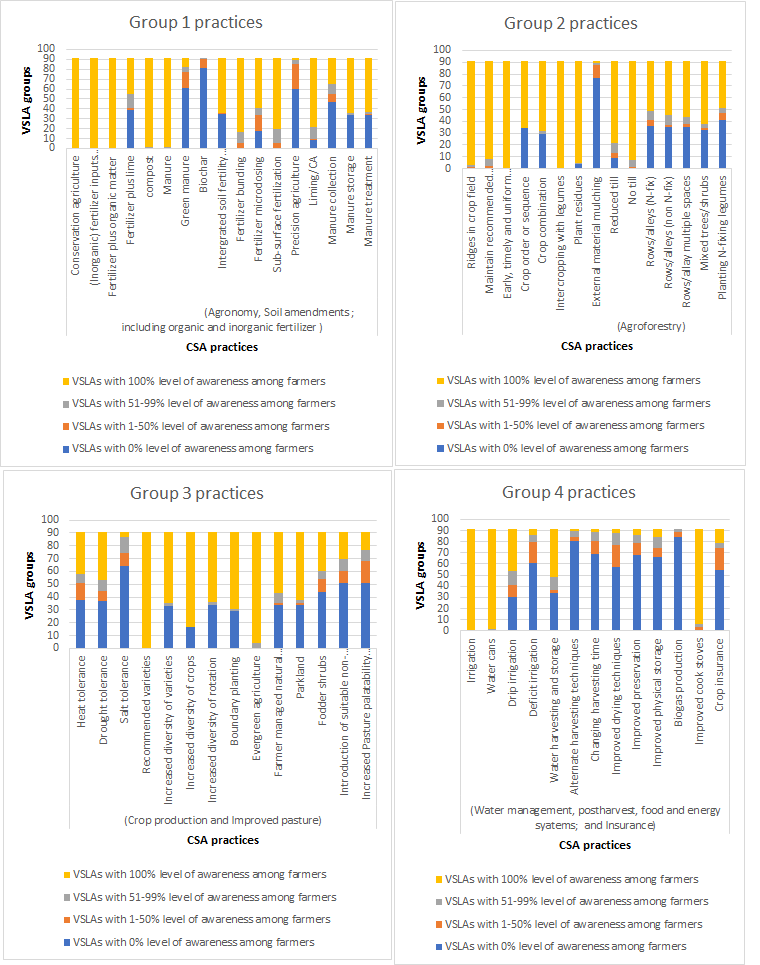

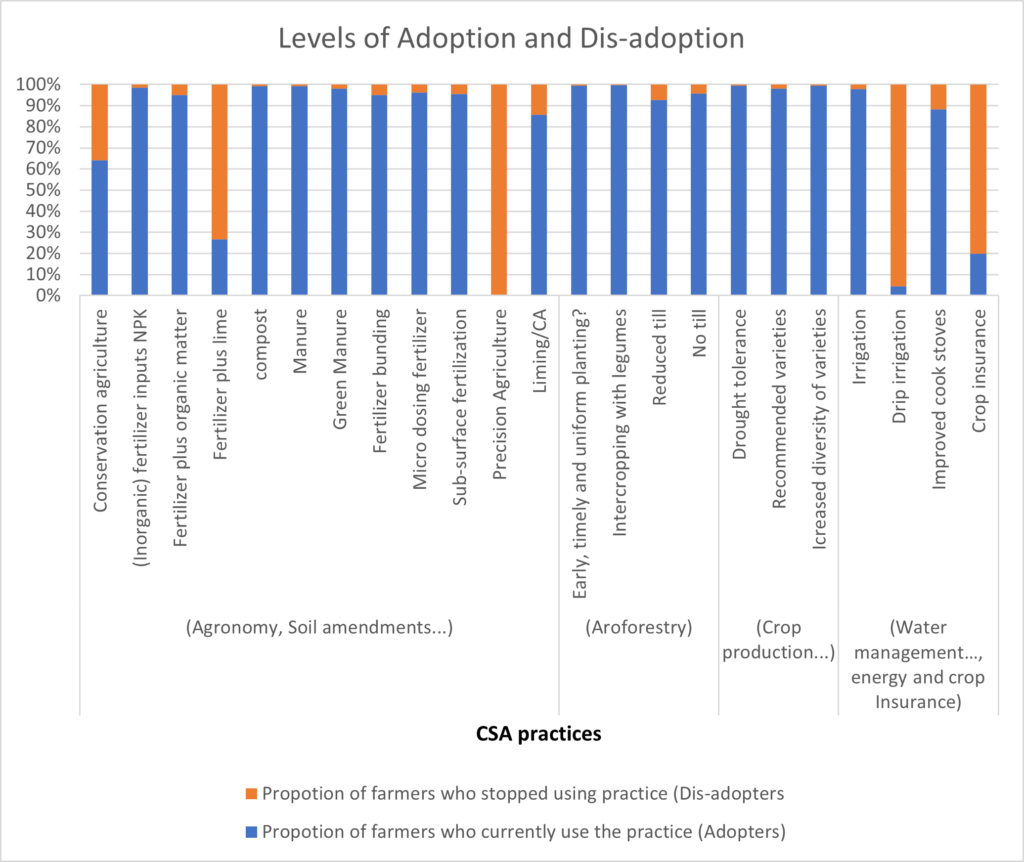

CSA technologies have been promoted by various CSA promoters in Malawi in recent years. Specifically, Dowa district of Malawi, which has over 90% of its population depending on agriculture, is a host to CSA activities which have been implemented for 5 years. The smallholder farmer participants of CSA technologies in Dzoole TA of Dowa district have benefited from the support given by various international donors, Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) and from the Government of Malawi to promote CSA technologies in that country. Although some research reports reveal that the district had some CSA adoption challenges, a study conducted under the 3D4AgDev Program within National University of Ireland Galway to explore the CSA practices awareness, adoption and dis-adoption among the farmers of VSLA groups in Dowa indicate that the level of adoption is greater than that of dis-adoption (Figure 1).

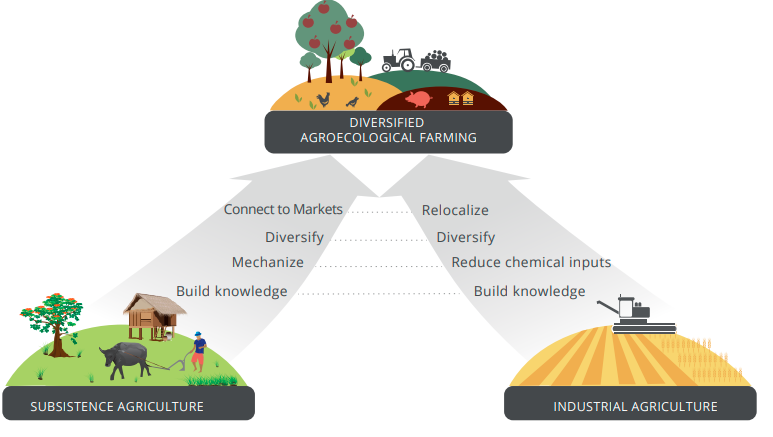

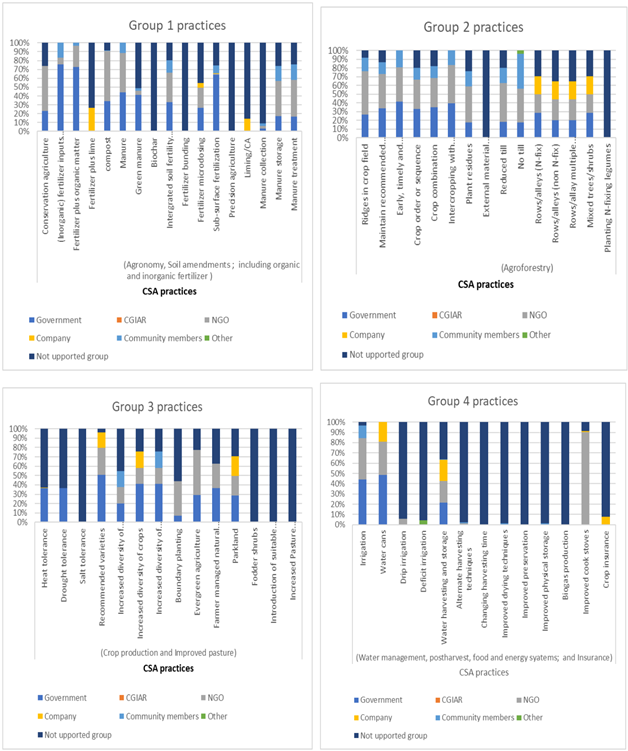

The above-mentioned result of adoption being greater than disadoption could have been influenced by the existence of CSA activities that were facilitated by multiple service providers/promoters of CSA that were active in the district. Our study showed that there was a pluralistic CSA dissemination system in operation among the VSLA groups. The CSA services were being promoted and being provided by a portfolio of Organizations that included government, NGOs, companies and community members (Figure 2).

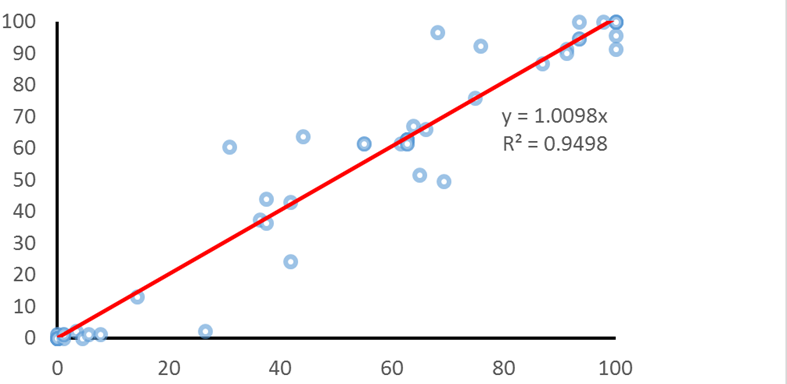

When a correlation analysis was conducted to assess the relationship between the levels of adoption of the CSA practices by VSLA farmers and the extent of institutional support/provision of CSA practices by different promoters, our results revealed a direct and tight positive relationship between the two variables assessed (Figure 3).

Despite the positive adoption rate shown by our study, it can still be argued that small scale adoption of CSA technologies by smallholder farmers in Malawi was still below expectation, with a few experiences of dis-adoption that were observed in some cases. Research suggest that dis-adoption of CSA practices are as a result of inadequate technical support received by the farmers in some parts of Africa during the challenging phase of implementation. The exploration into the CSA practices awareness, adoption, and dis-adoption among the farmers of VSLA groups reveal that farmers decide to dis-adopt CSA practices due to implementation bottlenecks such as the withdrawal of support from CSA service providers/promoters. Other farmers dis-adopted CSA practices such as use of inorganic fertilizers because they found locally affordable alternatives; substituted inorganic fertilizers with manure and compost

References:

CHINSEU, E., DOUGILL, A. & STRINGER, L. 2019. Why do smallholder farmers dis‐adopt conservation agriculture? Insights from Malawi. Land Degradation & Development, 30, 533-543.

KASSAM, A., FRIEDRICH, T. & DERPSCH, R. 2019. Global spread of conservation agriculture. International Journal of Environmental Studies, 76, 29-51.

NKALA, P., MANGO, N. A., CORBEELS, M., VELDWISCH, G. J. A. & HUISING, E. J. 2011. The conundrum of conservation agriculture and livelihoods in Southern Africa.