Should we be striving to ‘build back’ the very structures that have exacerbated the coronavirus pandemic? While the comparison has been made of the global SARS-CoV-2 outbreak to that of impending global climate disaster, in that inability for state actors to work together for global solutions, it has also highlighted the inefficiency of government as a structure with regards to domestic social welfare and public healthcare infrastructure.

“The emergence of a new pandemic was not unexpected given the increased understanding of how population growth and urbanization, habitat destruction, globalization of trade including live animal trade, and intensive livestock farming increase risk of transmission of zoonotic pathogens (Gibb et al., 2020, Plowright et al., 2017). Indeed, such human activities have contributed to the repeated emergence and spread of several zoonotic diseases since 2002 such as SARS (SARS-CoV), MERS-CoV, Zika and Ebola, all caused by viruses (OECD, 2020). These human activities, compounded by the increase in international mobility and weakened public health systems, created optimal conditions for the emergence and transmission of SARS-CoV-2.“

Barouiki et al. 2021

The likelihood of increased incidence of zoonotic and epizoonotic diseases as a result of climate change is only one element of concern, not only within agricultural livestock, but also wild populations (additional reading)

The only clear way to build back better after Covid 19 is through transformative change in order to build a new foundation both culturally and governmentally; one based in equity and sustainability, rather than that of extraction and exploitation. The possibility of framing of climate change as a public health issue might have been compromised by government negligence throughout the pandemic, but it is still vital to engage with the global public health narrative.

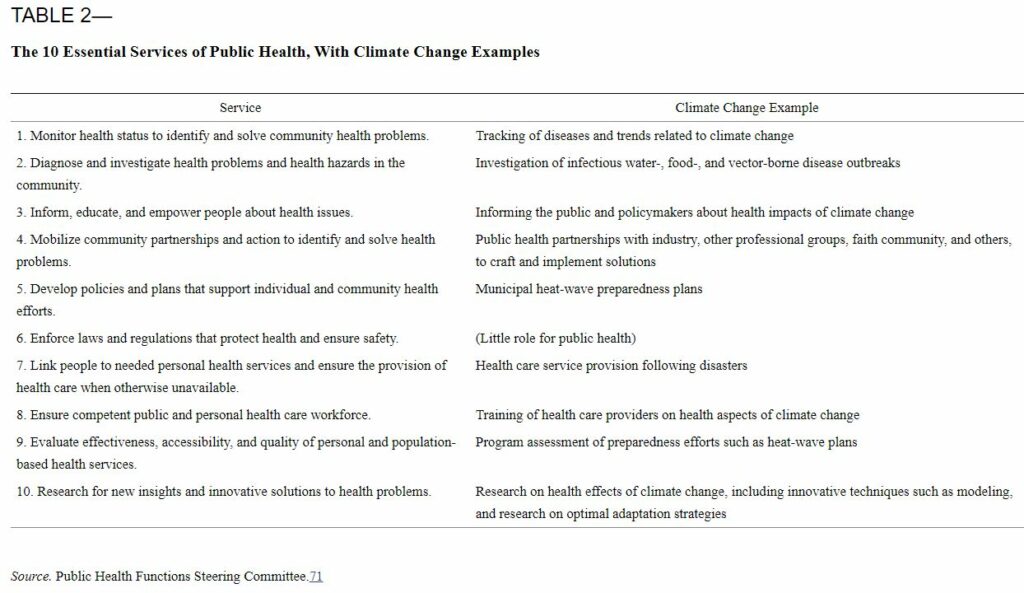

While this table is demonstrating climate change into public health, the inverse is also a potent factor for enacting change in governmental policy; incorporating public health, and human rights as such, into climate policies can alter current failing infrastructure as an adaptation measure.

Barouki, R., Kogevinas, M., Audouze, K., Belesova, K., Bergman, A., Birnbaum, L., Boekhold, S., Denys, S., Desseille, C., Drakvik, E., Frumkin, H., Garric, J., Destoumieux-Garzon, D., Haines, A., Huss, A., Jensen, G., Karakitsios, S., Klanova, J., Koskela, I.-M., … Vineis, P. (2021). The COVID-19 pandemic and Global Environmental Change: Emerging Research Needs. Environment International, 146, 106272. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2020.106272

Frumkin, H., Hess, J., Luber, G., Malilay, J., & McGeehin, M. (2008). Climate change: The Public Health Response. American Journal of Public Health, 98(3), 435–445. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.2007.119362

Hale, V. L., Dennis, P. M., McBride, D. S., Nolting, J. M., Madden, C., Huey, D., Ehrlich, M., Grieser, J., Winston, J., Lombardi, D., Gibson, S., Saif, L., Killian, M. L., Lantz, K., Tell, R. M., Torchetti, M., Robbe-Austerman, S., Nelson, M. I., Faith, S. A., & Bowman, A. S. (2021). SARS-COV-2 infection in free-ranging white-tailed deer. Nature. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-04353-x