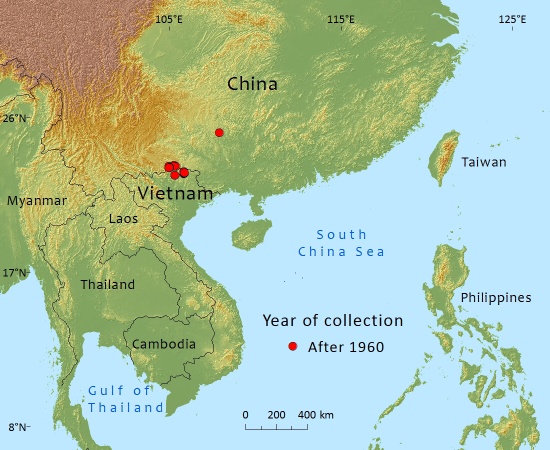

This week I had the opportunity to visit Ma climate-smart village in Yen Bai province, a couple of hours north-west of Hanoi.

As we cleared the city on Thursday afternoon and gradually rose in elevation, the air cooled and became noticeably cleaner. It’s surprising how quickly one can become accustomed to the the fumes of the city – I didn’t expect the contrast to be quite so stark and I’ll be taking a leaf out of Hanoians’ book and wearing a face mask when in traffic from now on!

I’d heard about Ma not just as a CSV but also as the location of a previous photovoice implementation which has led to the creation of a farmers’ communication group. The photos and exhibition stands from that project were stacked in a corner of the village hall, the sun already giving them an antique feel before their time.

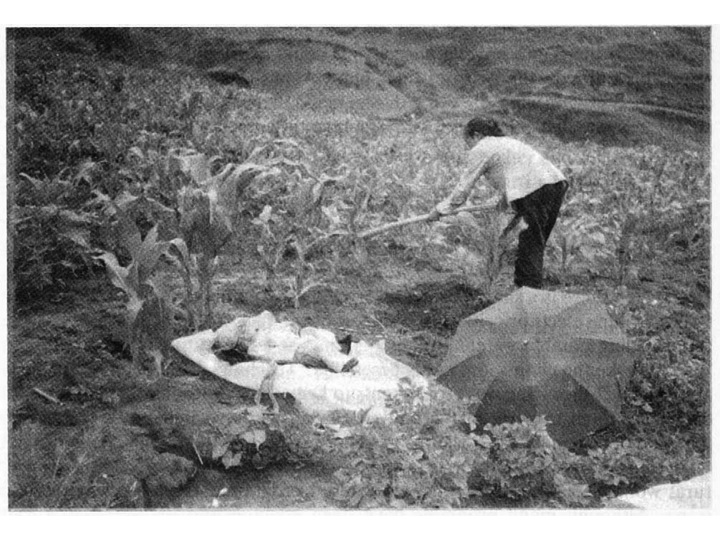

But we were not there to look at photos. It is coming into peak harvest season now and our visit was to hear about the results of trials being run by NOMAFSI using a participatory breeding approach with the farmers in Ma. Both different varieties and different management strategies have been trialled and now that the crop is ready to harvest, it was time to see it in the field before it’s brought in and the yields are assessed on scales and graphs.

I’m no expert on panicles and grain filling so I won’t start on that. However, even to a novice eye, there were clear differences between several of the varieties trialled, both in height and apparent vigour. I was informed that the quality of grains is also becoming more and more important as buyers and end-consumers become increasingly aware of nutritional content.

Perhaps more interesting than the varieties per se was the discussion of management strategy. Integrated Crop Management (ICM ) is the term applied to the suite of practices that NOMAFSI is attempting to introduce, and seeks to influence all aspects of how the rice is grown, from field preparation and planting to fertiliser management during the growing season, and management of the rice straw post-harvest. Farmers acknowledged that the biggest gain was in consistency across a field, and that this seemed to lead to an overall better yield. The trade-off is that the practice requires a little more planning and care when planting and for fertiliser application. For example, lines need to be laid out in regular rows for planting and fertiliser application can’t just be a random broadcasting across the plot.

Also interesting was the discussion of how to deal with the rice straw, or ‘stubble’ as we might call it in Ireland, after the crop has been harvested. In order to speed the decomposition of the straw and facilitate a quick turnaround for the next crop, farmers sometimes apply a herbicide that does just that – speeds up the decay of the organic matter left standing in the field. Although this works, the chemical (I didn’t manage to get the name of the active ingredient) is damaging to soil life and the practice isn’t sustainable long term. The alternative is a biological decomposing agent that can be applied in a similar way. This takes a little bit longer to work its magic but its effect on soil life is beneficial and it helps to retain and build organic matter in the soil.

Back in the hall, the discussion was animated and farmers (mostly women) weren’t shy in expressing their thoughts on the pros, cons, and tradeoffs. Before it all ended, I was asked to say a few words about why I was there and it was nice to be able to tell the folks there that word of the climate-smart village in Ma has already made its way to lecture rooms in Ireland. Long may it continue.