“Fixing food is a unique and powerful opportunity to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals by 2030”1. The humble school lunch and kitchen garden are a hugely undervalued and underutilised resource in this endeavor; not only in the food provided but (and perhaps more importantly) in the lessons learnt.

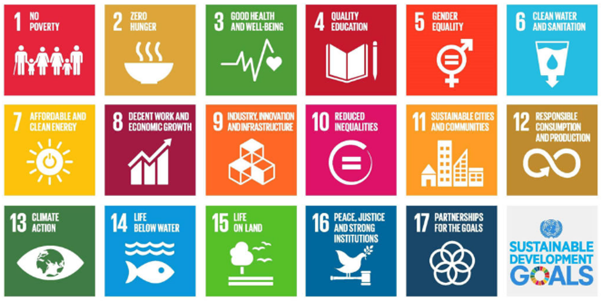

Later this year, the UN Secretary-General will convene a Food Systems Summit to launch bold new actions to transform the way the world produces and consumes food. To deliver progress on all 17 of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), preparations across 5 Action Tracks are being made. The focus of Action Track 2 (AT2) is ‘Shifting to Sustainable and Healthy Consumption Patterns’. As part of its preparation, the AT2 Public Forum Discussion was held in December 2020. A common thread among its speakers was the role of social norms in our food systems and how, in changing these norms, we can begin to break down the barriers to progress such as meeting the SDGs.

Within this discussion, Dr. Gunhild Stordalen, Founder and Executive Chair of EAT, highlighted how with growing urbanisation, people have shifted away from their traditional practices and diets. Within the urban landscape, ultra-processed foods and beverages are replacing healthy and nutritious wholefoods. Consequently food has now become the biggest killer of all, for both people and the planet. We are witnessing rising obesity and cardiovascular disease together with escalating land degradation and biodiversity loss. However, Dr. Stordalen also argued “Food can be the most powerful medicine for both people and planet”.

So far, in a typically western style, we have taken a limited view on such an idea and sought to alleviate the symptoms and ignore the disease. Tax schemes for fat, sugar and meat have been implemented but to limited success. Not only do these schemes hit hardest those with the least capacity for choice, they ignore the social norms and foundations of our food systems. As AT2 keynote speaker and chef Sam Kass stated, “When we talk about changing the system, we run directly into people’s identity”. Early exposure to cultural norms shape the way we as children form our self- identity, including what we eat. So, if we are to change our relationship with food, what better place to start than in the playground.

The scientific data tells us that the introduction of food based school gardens, as a component of early education, increases knowledge of fruits and vegetables and creates skills and attitudes conducive to enhancing their consumption 2, 3, 4. Critically, the data also shows this behavior continues into adolescence 4. As discussed in the AT2 forum, not only must we adopt healthy eating habits, we must maintain them throughout our lifetimes. So while school gardens are not a novel concept, innovation is needed in the scale at which they must be implemented and the landscapes in which they are most needed.

Almost 20 years ago, the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) released the ‘School Gardens Concept Note’ 5 which outlined the strategic elements necessary for a national School Garden Program. It showed how previous attempts at similar programs had failed because of a lack of attention to the institutional framework. It highlighted the need for political commitment and national policies. We must demand then of our governments (quite literally as a matter of life and death) the national institutional frameworks needed to ensure long term success of educational gardening programs.

For me, the only point of contention in the Concept Note was one of geography. It had at the time identified rural areas as most in need of intervention, but by 2050 by nearly 10 billion people will be living in cities (according the United Nations). A recent UNICEF Report focused on the food challenges faced by children in urban settings; where fast food and packaged snacks are readily available and where outdoor spaces to gather and play are limited. It stated in no uncertain terms, “The need to transform the food environment in cities is clear and urgent” 6.

To meet the food challenge in the urban landscape, we must be extra innovative and inventive. We must incorporate into the institutional frameworks, new stakeholders and new knowledge. Experts in small space gardening, architecture and urban planning. Those whose’ knowledge of big cities and small spaces can be used to create a new city dwelling identity. Such an identity, a new collective attitude and relationship to healthy food, will help us go beyond the single issue of poor diets towards the collective goal of the SDGs.

By ensuring these programs and innovations are implemented in the most inner city schools, we can create ‘Sustainable Cities and Communities’. By having students eat what they grow, we can begin to address ‘Zero Hunger’ and ‘Good Health and Well-being’. By teaching new skills in horticulture and food science, city students may access employment opportunities and ‘Economic Growth’ otherwise excluded to them. By ensuring such programs are integrated into the earliest of learning, regardless of race, gender or background, we can contribute to ‘Quality Education’, ‘Gender Equality’ and ‘Reduced Inequalities’.

To create a new cultural identity and turn our food into medicine, we must literally plant the appetite for change.

1 – United Nations Action Track Discussion Starter. Action Track 2 – Shift to healthy and sustainable consumption patterns. www.un.org/sites/un2.un.org/files/unfss-at2-discussion_starter-dec2020.pdf

2- Somerset, S., & Markwell, K. (2009). Impact of a school-based food garden on attitudes and identification skills regarding vegetables and fruit: a 12-month intervention trial. Public Health Nutrition, 12(2), 214-221

3- Parmer, S. M., Salisbury-Glennon, J., Shannon, D., & Struempler, B. (2009). School gardens: an experiential learning approach for a nutrition education program to increase fruit and vegetable knowledge, preference, and consumption among second-grade students. Journal of nutrition education and behavior, 41(3), 212-217

4- McAleese, J. D., & Rankin, L. L. (2007). Garden-based nutrition education affects fruit and vegetable consumption in sixth-grade adolescents. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 107(4), 662-665

5- FAO (2002), SCHOOL GARDENS CONCEPT NOTE Improving Child Nutrition and Education through the Promotion of School Garden Programmes. Rome. www.fao.org/3/af080e/af080e00.pdf

6- United Nations Children’s Fund, The State of the World’s Children 2019: Children, food and nutrition – Growing well in a changing world, UNICEF, New York.