It has become increasingly easy in the globalized and industrialized world we live in to use and replace resources such as mobile phones, clothes and food; resulting in a ‘linear’ model whereby resources are used and thrown away (MacArthur, 2013). In contrast, the ‘circular economy’ approach refers to a cycle of production and consumption whereby waste is minimized or used for another purpose (MacArthur, 2013). The Platform for Accelerating the Circular Economy (PACE) launched the ‘Circular Economy Action Agenda’ on the 4th February 2021, bringing together speakers from different sectors and disciplines who all agreed that a circular economy approach is needed to meet sustainability and climate goals. UNEP Executive Director Inger Andersen outlined at this session that the Paris Agreement and NDC commitments are a step forward towards emission reductions and mitigation of climate change, however we must go further towards circular economies with biodiversity and environmental protection as a priority.

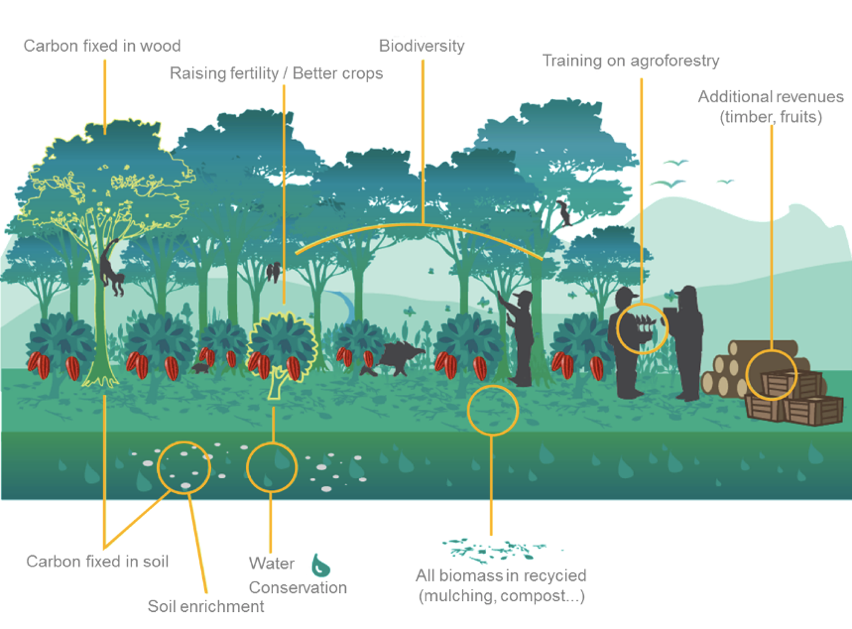

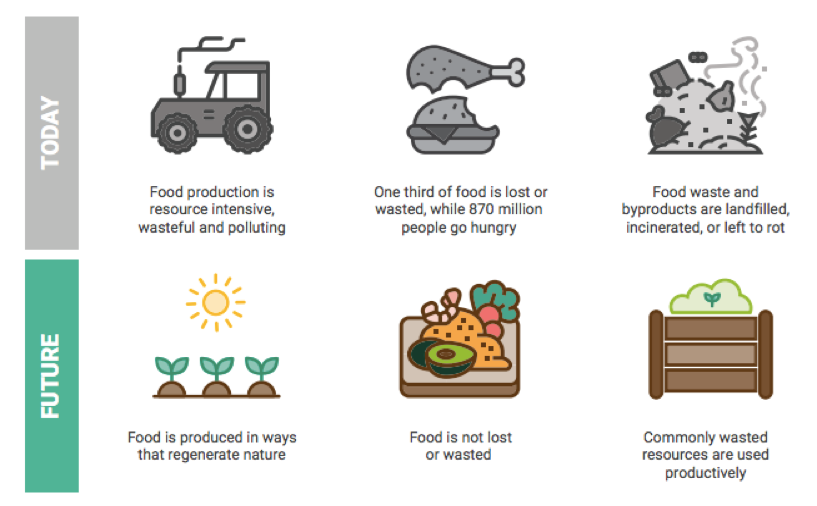

Food and agriculture systems are at the core of biodiversity and environmental protection and have gained focus as a staggering one third of food is lost between production and consumption (FAO, 2011). The PACE Circular Economy Action Agenda report for food systems outlines three main objectives: to change what food we grow and switch to regenerative practices, reduce food loss and waste, and make use of waste products (PACE, 2021). Figure 1 illustrates these approaches, which would facilitate a more productive and efficient food system promoting sustainability, reduced emissions, creation of jobs, improved food and nutrition security and protection of biodiversity (PACE, 2021).

PACE (2021) note that a barrier to using waste as a resource is the perception that it holds no value, meaning that companies are not enticed to create innovations. Despite this, Toast Ale breaks this perception and is aligned with the aims of the PACE Circular Economy Action Agenda to mitigate and make use of food loss and waste. As an astounding 44% of bread in the UK is wasted (Zaine, 2019), Toast Ale was founded in 2015 as craft beer company standing out from the crowd by using wasted bread as an innovative ingredient (Toast Ale, 2019). Toast Ale uses bread that would otherwise go to waste as a partial substitute to virgin barley in the brewing process, resulting in a ‘triple win’ for sustainability by reducing food waste and associated emissions, reducing the land and water needed to grow barley and reducing the emissions that would result from barley production and transportation (Toast Ale, 2019; Zaine, 2019). As of 2019, using wasted bread in the brewing process has resulted in a saving of 11 tonnes of CO2e, 108.4m3 of water and 7.5 hectares of land (Toast Ale, 2019). The waste produced by Toast Ale is also valued, as it is delivered back to farms where it can be used to feed animals and fertilize soils (Zaine, 2019).

The PACE Circular Economy Action Agenda (2021) calls for transparency through open source data and information sharing within the food and agriculture sector, allowing innovations to be implemented at scale. As part of their sustainability strategy and to keep their environmental footprint low, Toast Ale do not take part in exporting beer but instead share their innovation with global breweries, facilitating wider adoption of this sustainable and circular process as well as minimizing wasted bread in landfill around the world (Toast Ale, 2019; Zaine, 2019). Through researching the brand, I discovered that Toast Ale is stocked at my local supermarket, and so I ventured out in the snow to try it for myself (Figure 2). I was pleased to see another brand named ‘Crumbs’ placed beside Toast Ale on the shelf – another brewery adopting the innovation with spare sourdough bread from a small bakery.

At the PACE Circular Economy Action Agenda launch, Jyrki Katainen, ex-prime minister of Finland and president of Sitra, reminded us that jobs will be lost to circular economy approaches and that social justice must be a priority. For example, using discarded bread in the beer brewing process means that less virgin barley is used. If scaled up significantly, this could potentially disadvantage farmers, food system workers and transportation staff who would be involved in this stage of the supply chain. I struggled to find much information regarding farmers and food system workers supplying Toast Ale on their website, highlighting that this may be a gap that needs addressed as the innovation is scaled up. Despite this, it is clear that social justice is undoubtedly at the heart of the Toast Ale business model with 100% of profits going to charities supporting food security and environmental protection (Toast Ale, 2019; Zaine, 2019).

Although Toast Ale are only a small part of the transformation towards a sustainable circular economy; catchy and informative marketing for a widely consumed and enjoyable product such as beer helps create awareness of challenges and sustainable solutions on a wider scale (Zaine, 2019). Overall, the brewing and craft beer industry is rarely considered as a key industry to tackle food loss and waste, however Toast Ale demonstrate that opportunities can be present where we least expect them to be.

References

Andersen, I. (2021). ‘Time to Act: The Circular Economy Action Agenda’, 04/02/21, Online.

FAO. (2011). Global food losses and food waste – Extent, causes and prevention. Rome.

Katainen, J. (2021). ‘Time to Act: The Circular Economy Action Agenda’, 04/02/21, Online.

MacArthur, E. (2013). Towards the circular economy. Journal of Industrial Ecology, 2, 23-44.

PACE. (2021). Circular Economy Action Agenda, Food. The Hague, The Netherlands.

Toast Ale. (2019). Toast Ale Impact Report. London.

Zaine, L. (2019). ‘Climate and Ecological Emergency’. Toast Ale. Available at: https://www.toastale.com/blog/climate-and-ecological-emergency/. Last Accessed 10/02/21.