The COVID-19 pandemic has caused huge global social and economic disruption. There has been an increasing debate about the impacts of the pandemic on global biodiversity and efforts to conserve it. Many scientists have since identified identify short-term benefits for biodiversity, such as less pollution as a result of reduced human activity, wildlife reclaiming human-dominated habitats, reduced impacts on Marine systems due to shipping declines, the decline in greenhouse gas emission. These may be short-term improvements, but they dramatically underline the pervasiveness and severity of anthropogenic impacts worldwide. Enforced shutdowns has made people more aware of the species and ecosystems around them, perhaps awakening public concern for the state of nature (Corlett et al., 2020; Helm, 2020)

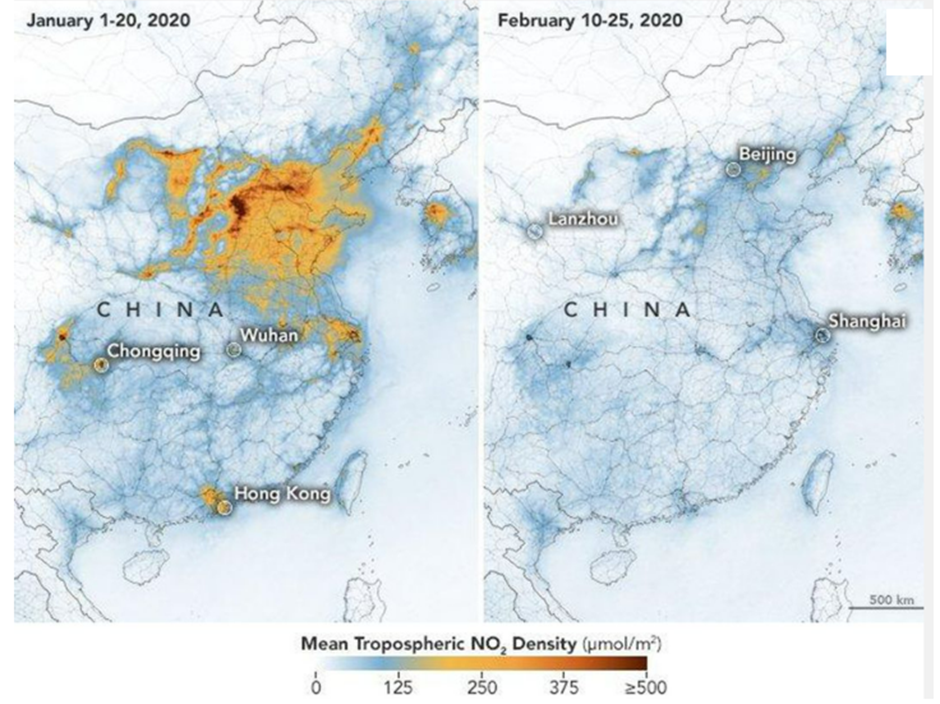

Satellite images have shown dramatic improvements in air quality in every country affected by the pandemic, as industry and transport shut down

The world is said to be facing it’s sixth mass extinction with over one million plants and animal species threatened with extinction due to changes in land and sea use, overexploitation, climate change, pollution, and invasive alien species (Diaz et al., 2019). Since 1970, populations of mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, and fish have declined on average by 68% and vast areas of ecosystems have been degraded (WWF, 2020). Many scientists have highlighted the linkages between biodiversity loss and infectious diseases and the importance of biodiversity for the economy

Green Recovery

Beyond the short-term impacts of the pandemic, there has been a growing debate on the shape of international and national policies for the world after COVID-19. Roy (2020) emphasized that there are various potential pathways, each of which entails a very different relationship between human society and non-human life on Earth. Even as much of the conservation sector is embroiled in a battle for survival in the midst of the crisis, it is essential to look to the future and weigh the consequences of different post-COVID-19 economic scenarios for conservation.

Many governments have implemented stimulus measures and recovery plans to create jobs and drive economic recovery and many of these interventions are associated with heavy biodiversity footprints, such as agriculture, energy, and industry. A key challenge for governments is to ensure that the measures they introduce effectively address immediate social and economic needs while promoting longer-term resilience, human health, well-being, and sustainability. With this in mind, government and business leaders across the globe have called for a green and inclusive recovery to COVID-19. This is known as a classic ecomodernist vision, which is a common debate about sustainable development since the 1970s (Adams, 2020). It lay at the heart of the Rio + 20 Conference, under the name of a Green Economy.

This shift implies an economy that is still capitalist, but cleverer and greener, where growth, markets, and corporations are turned into conservation allies and where biodiversity conservation becomes an agent of green economic development, However, the focus of this rhetoric and the green stimulus measures introduced to date has largely been limited to climate change, with much less attention given to biodiversity. Biodiversity loss and climate change are challenges of a similar magnitude and urgency and are fundamentally interlinked. They must be addressed simultaneously as part of broader efforts to achieve a green and inclusive recovery.

Conclusion

To safeguard biodiversity and help drive improvements in environmental sustainability, it is imperative that governments keep longer-term policy goals in mind when designing and allocating loans, grants, tax relief, and other support for companies. To avoid future pandemics and other crises, maintaining or stepping-up regulations on land-use change, wildlife trade and polluting activities are critical. Furthermore, by shining a light on the links between human health and biodiversity, the COVID-19 pandemic may have provided a political window of opportunity to tighten regulation that it does not continue to erode biodiversity and ecological life-support systems.

Interesting readings to Learn more on the links between biodiversity conservation and Covid 19;

ADAMS, W.M. (2020) Green Development: Environment and Sustainability in a Developing World. 4th edition. Routledge, London, UK

Roe, D. et al. (2020), Beyond banning wildlife trade: COVID-19, conservation and development, Elsevier Ltd, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105121.

ROY, A. (2020) The pandemic is a portal. Financial Times,3 April 2020. ft.com/content/10d8f5e8-74eb-11ea-95fe-fcd274e920ca [accessed 22 June 2020].

CORLETT, R.T., PRIMACK, R.B., DEVICTOR, V., MAAS , B., GOSWAMI, V.R., BATES, A.E. et al. (2020) Impacts of the coronavirus pandemic on biodiversity conservation. Biological Conservation, 246, 108571

HELM, D. (2020) The environmental impacts of the coronavirus. Environmental and Resource Economics, 76, 21–38

Diaz, S. et al. (2019), Summary for policymakers of the global assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services, IPBES, https://www.ipbes.net/system/tdf/ipbes_7_10_add-1- _advance_0.pdf?file=1&type=node&id=35245 (accessed on 6 September 2019).

WWF (2020), Living Planet Report 2020 – Bending the curve of biodiversity loss., WWF