Rural transformation for a socially inclusive and sustainable future

The focus for my thesis was on rural communities (mainly through an agricultural lens) in developing countries as they are amongst the most vulnerable groups to the devastating impacts of climate change even though they have the smallest carbon footprints. In fact, according to the World Bank, the world’s seventy-four poorest countries have only contributed one tenth to global greenhouse gas emissions, highlighting the uneven and unfair distribution of the negative impacts of climate change (World Bank, 2021). Take Pakistan for example, who are currently experiencing one of the worst climate crises now. Melting glaciers from unprecedented temperature highs of 53°C combined with the heaviest monsoon rains for over a decade (described as a monsoon on steroids by the UN chief) has left more than a third of the country submerged in water with 1136 deaths recorded so far. Pakistan has a large population of 220 million people yet their contribute less than .6% to global greenhouse gas emissions and already one of most heavily affected countries by the climate crisis (see Our World in Data for information on other countries contribution to GHGs). Crops have been destroyed and food prices are soaring as a result putting the most vulnerable at risk of falling into extreme poverty and suffering from food insecurity.

The climate crisis is set to further exacerbate conditions for the world’s poorest and widen the gap in the distribution of productive resources between the rich and the poor. This was the motivation to write my review paper as I wanted to discover why some rural communities, who produce food for the rest of the world are still living in poverty, barely able to feed themselves and live a decent life. Many reports refer to the vulnerabilities of rural communities. The IPCC’s “Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability” report, the UNDP’s “Multi-dimensional Poverty Index Report” and the World Food Program’s “Global Report on Food crises” all highlight the multi-dimensional poverty, food insecurity and climate vulnerability of rural communities due to either their marginalised locations, social exclusion, socioeconomic status, or weak governance.

As mentioned in my previous post, alleviating poverty is one of the biggest challenges to sustainable development. Many of those living in poverty are concentrated in rural areas and are reliant on one of the most climate sensitive sectors: Agriculture (Castaneda et al., 2016).

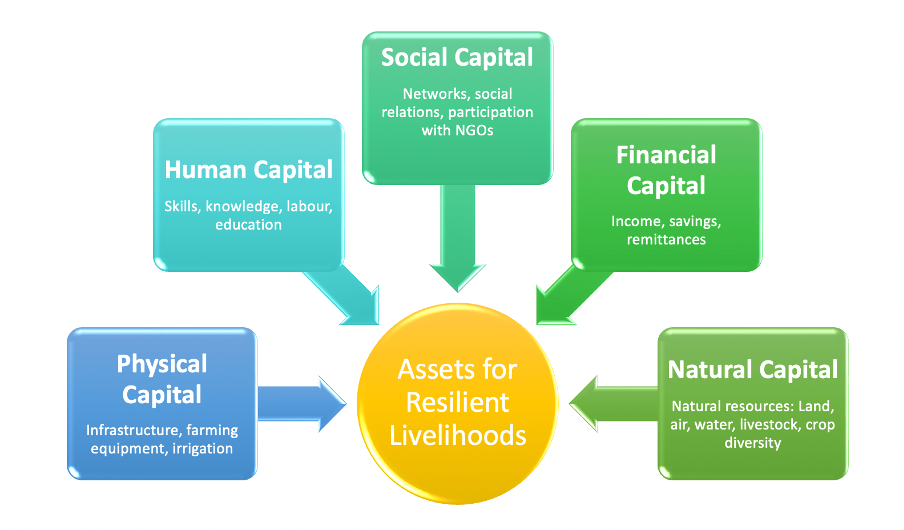

Smallholder farmers are amongst the poorest and most vulnerable segments of rural societies. Without intervention, these farmers will not be able to escape their cycles of poverty which makes achieving the SDGs impossible. Therefore, it is important to tackle poverty at its source in a bottom-up approach. After reviewing the literature, we found significant evidence that suggests the positive impacts of rural transformation on sustainable development. Transforming the agricultural sector can create jobs both on and off the farm and create a vibrant rural economy which will entice skilled workers to stay in their communities rather than migrating to urban areas. For agriculture to have a truly transformative role and create thriving rural economies, there needs to be a clear understanding of who the poorest groups are, what sectors they work in why they have been left behind and what interventions are suitable to their circumstances to help them reach their desired livelihood outcomes. Smallholder farmers are a diverse segment and often characterised by the size of their landholdings which can be anywhere between two and ten hectares. However, there are far more dimensions to the definition of a smallholder. The world ‘small’ may refer to a scarcity of resources or assets (figure 1) which are essential components to securing livelihoods. Although lacking modern technology and access to improved inputs, smallholder farmers produce around 35% of the world’s food calories (Lowder et al., 2021) and are highly productive per unit area of land due compared to large scale farmers (Woodhill et al., 2020). To unlock the potential of the smallholder sector there needs to be an understanding of their heterogeneities to aid policy design and to allow for effective targeting of resources and social protection packages.

Adding to Smallholder farmer’s vulnerabilities is their reliance on ecosystem services to maintain their crops and livestock for their subsistence (IPCC, 2022). With the increased instances of drought, flood and temperature anomalies, ecosystem services will be in sharp decline and the farmers relying on these services will suffer as a result.

It is well known that for any farmer, land and its associated resources are the biggest asset they can have. Without access to land or having ownership of land farmers have nowhere to work and their skills often do not transfer into other sectors. This is a huge problem in many developing countries. A lack of secure land tenure (the ability to make decisions or own land) severely hampers with farmers ability to increase their productivity and adopt climate resilience and adaptation practices. Formalising land rights can be a huge step to creating an enabling environment that can lead to farmer agency and a brighter outlook on the future.

When investing in formalising land rights, understanding the complex nature of tenure systems around the world will be important for policy and program design. In figure 2 below, we can see the most the basic dimensions of secure land tenure as identified by Place et al., 1994. Securing the three dimensions of secure tenure can give farmers a sense of security and motivation to ensure the quality of their land of time and to adopt more environmentally friendly and productive practices. Have a look at this video from the UN-habitat on their work in securing land tenure for rural communities in Uganda.

Smallholders are a vulnerable group, but there is hope for them, it will require collecting mass data from all segments of rural societies to help unpack the solutions required to help them achieve successful livelihoods. In my next post I will be discussing some of the benefits of social protection for the most vulnerable societies.