Micronutrients are vitamins and minerals that cannot be synthesized in the human body, instead derived from the diet. They are needed in small quantities by the body but are essential for good nutrition, proper growth and development, and overall health. Their deficient can have a substantial negative health impact, which can either be reversed with the provision of missing micronutrients or irreversible, leading to lifelong consequences and sometimes results into death depending on severity, timing, and the extent of the shortage (Bailey, West Jr, & Black, 2015). Inadequate intake of these essential micronutrients can lead to Micronutrient Deficiency (MND), also known as hidden hunger (Young, 2012) since the symptoms of insufficiency are less noticeable (Muthayya et al., 2013).

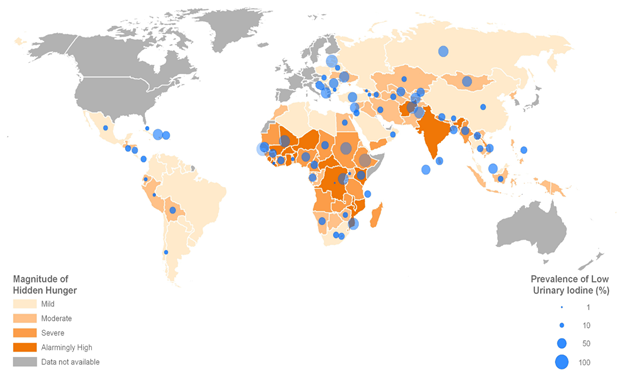

Micronutrient Deficiency is widespread but high in Sub Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia (Ramakrishnan, 2002). It is estimated to affect two billion people worldwide with insufficient vital vitamins and minerals, particularly vitamin A, iron, iodine, and Zinc (Bailey et al., 2015). Folate, B12, and Riboflavin are also common deficiencies. Children under the age of five and pregnant women in low-income countries are the most vulnerable groups. Additionally, most developing countries are suffering from Multiple Micronutrient Deficient (MMD), a situation where the same population faces more than one micronutrient Shortage (Allen, Peerson, & Olney, 2009). MND accounts for almost 7% of Global Disease Burden each year (Ezzati, Lopez, Rodgers, & Murray, 2004).

The leading cause of Micronutrient Deficiency is low dietary diversity, involving a high intake of starchy stable food like cassava, rice, and maize and low intakes of micronutrient-rich food like vegetables, legumes, and animal source food. The latter is the richest in micronutrients that are difficult to obtain in adequate quantity from plant source food alone (Murphy & Allen, 2003). Low bioavailability on the nutrient in diets and nutrient loss due to illness are other causes of MND. Some diseases exacerbate micronutrient deficiencies due to the rapid loss of nutrients through vomit or feces (Golden, 2002). Micronutrient deficiency also worsen infectious and chronic diseases and cause-specific diseases that significantly impact morbidity, mortality, and quality of life (Tulchinsky, 2010)

Vitamin A

Vitamin A, which is stored by the liver, is fat-soluble with several body roles, including support health eyesight (vision), immune function, cell differentiation, reproduction, and formation and growth of organs and bones (World Health, 2009).

Vitamin A can be directly sourced from the animal diet as retinol (retinoic acid), by consuming food like liver and eggs. Alternatively, vitamin A can be sourced from a plant, through consuming β-carotene foods, which is the primary dietary source of Vitamin A, referred to as provitamin A.

Provitamin A carotenoids, which exhibit differential vitamin A activity, are converted to the active forms of the vitamin (retinal) for use by the body (Bailey et al., 2015; World Health, 2009). It is the most abundant and efficient carotenoid, available in a wide range of orange/yellow fruit and vegetables, and dark green leafy vegetables, whereby their β-carotene contents vary according to the season and degree of ripening.

Vitamin A deficiency (VAD) consequences are more apparent during life stages of increased nutritional demand like early childhood, pregnancy, and lactations and affect mostly women of reproductive age and children below five years.

Lack of inadequate intake of vitamin A impaired by high rates of infections, especially diarrhea and measles. Vitamin A deficiency (VAD) leads to night blindness, which might cause xerophthalmia (eye fails to produce tears) condition that triggers cornea ulceration if untreated. It is the leading cause of preventable blindness in children and the primary cause of childhood morbidity and mortality in the developing world (Bailey et al., 2015). Globally, Vitamin A Deficiency (VAD) estimated to affect almost 190 million preschool children and 19.1 million pregnant women (serum retinol <0.70 μmol/l) (WHO, 2011), and has caused blind to 250 – 500 million children and half of them die within a year of vision loss, as well as being common during pregnancy by 10 -20% (Bailey et al., 2015).

In Tanzania, Vitamin A Deficiency (VAD), affecting 33.5% of children aged 6-59 months (Ministry of Health et al., 2016; National Bureau of Statistics & Macro, 2011) and 36% of women between the ages of 15-49 (Dalberg, 2019; Ministry of Health et al., 2016; National Bureau of Statistics & Macro, 2011). Therefore, preventing iron deficiency is essential for improving children’s learning ability and cognitive development.

Iron

Iron is an essential mineral in the human body for making hemoglobin and myoglobin. Hemoglobin is a protein found in red blood cells that transport oxygen from lungs to the organs and tissues throughout the body, and myoglobin is supplying oxygen to muscles; hence iron is vital for brain and muscle function and cellular respiration. Iron is also an essential component of enzymes and cytochromes, therefore crucial for protein metabolism in the body (Food-and-Nutrition-Board, 2001).

Iron helps boost the immune system of the body, growth, and development of the body (cognitive development) as it creates energy from nutrients.

Iron sourced from animal (heme form) by consuming food like meat, liver, fish, and sourced from plants (nonheme) for products like legumes, beans, cereals, and leafy vegetable example, spinach. Dairy products like milk, also categorized as nonheme products. Heme and nonheme iron forms are highly bioavailable with an estimation of 12–25% and <5%, respectively. However, the body’s Iron contents are highly conserved, except for menstruating and pregnant women (Food-and-Nutrition-Board, 2001).

Iron deficiency is the leading cause of anemia (Bailey et al., 2015), and it disrupts the optimal function of the endocrine and immune systems. Anemia decreases the total amount of red blood cells (RBCs) or hemoglobin in the blood and is the most common during pregnancy due to increased fetal growth and development (Bailey et al., 2015). Worldwide, 24.8% of the population estimated to be anemic, with preschool children and pregnant women having the highest prevalence of 47.4% and 41.8%. Africa had 67.6 and 57.1% for preschool children and pregnant women, and Southeast Asia 65.5 and 48.2% (WHO, 2008).

Iron is the most common micronutrient deficiency for more than two billion people (30%) (WHO, 2008), affecting 43% of children below five years of age and 38% of pregnant women (Haas & Brownlie, 2001). It increases maternal death risk for the mother and low birth weight for the infant, causing premature delivery and other perinatal complications. Each year between 2.5 and 3.4 million deaths on maternal and neonatal (Haas & Brownlie, 2001), anemic contributes up to 20% of maternal mortality. Meanwhile, iron deficiency is one factor contributing to One hundred sixty million children below five years stunted, 50 million children below five years wasted (Black et al., 2013; Myers et al., 2017).

In Tanzania, 58% and 29% of children between the ages of 6-59 months and Women of Reproductive Age (WRA) are anemic. Moreover, 16% of WRA mildly are anemic, 12% moderately anemic, and 1% as severely anemic (Ministry of Health, 2016; TNNS, 2018).

On top of that, 31.8% of children under five years of age stunted, 14% are underweight, 3.5% wasted, and 2.8% are overweight (TNNS, 2018), as well as 7.3% of women of reproductive age (15-49 years) are underweight, 31% are overweight, and 10% are obese (TNNS, 2018).