I think its time to talk about mites. The Tetranychus species are commonly referred to as red spider mites. The different species are difficult to tell apart as they are all a rusty red in colour. The red spider mites have a world wide distribution but are most common in the tropics and subtropics. There any many crops that are hosts to the spider mites, these include: okra, papaya, sweet potato, tomato, eggplant, beans, taro, cucumber, squash and of course cassava which is the host crop I am studying.

Symptoms & Life Cycle

Spider mites are common plant pests. They have needle-like mouthparts and use them to suck juice from the leaves. This destroys the cells, and the leaves show a characteristic white to pale yellow speckling, often along the sides of the main veins When infestations are severe, the speckling is seen all over the leaf. Some species of red spider mite such as the two-spotted mites make webs (like spiders) on the under and on the upper surface during an infestation as the infestation advances, the leaves turn yellow and die prematurely. The eggs are round and relatively large in comparison to the size of the adult; they are laid in the webbing near the veins, on the underside of leaves. The webs allow the mites to travel from infested to non-infested leaves; also, the webs are caught by the wind and help the mites to disperse by this method also. The eggs hatch 3 days after being laid producing larvae that have six legs and are colourless. From these, nymphs develop, which have eight legs; they moult once and within a few days become adult. The adults are about 0.5 mm long, with males smaller than females, and narrower towards the back end. Each female lays about 100 eggs. Under tropical conditions the life cycle takes only 7-10 days depending on temperatures. Populations develop rapidly, especially during periods of drought when damage can be considerable. The adults live for 2-4 weeks.

Impact

The extent of the damage caused by mites often depends on rainfall. When rainfall is low, mite populations are high and reduce crop yields. On cassava, for instance, yellowing of the leaves and early maturity of plants occurs and the size of the root tuber is reduced. The overall crop yield is also reduced. Damage is particularly severe during droughts and it is thought that outbreaks will increase with climate change.

Management

There are different ways to manage mites:

CULTURAL CONTROL

- A regular spaying of leaves with water can keep spider mites in check.

- Check that cuttings, “tops”, and other kinds of planting materials are free from mites infestation before planting in a new garden.

- Weed: remove plants that are common hosts of spider mites, e.g., wild Amaranthus

- The problem with cultural control is that it is very time consuming especially if you are managing a large area of land or many different fields which is the case where I am carrying out my research.

CHEMICAL CONTROL

- Pesticides can be used but they should be applied carefully, rotating between different chemical groups, to prevent resistance developing to any one of them.

- Not all insecticides kill mites, and those that do may not kill all the stages. Eggs are particularly resistant to pesticides and so, too, are larvae and nymphs, especially when moulting, as they do not feed. More than one application is needed at 5-10 days apart.

- Aside from the difficulties associated with pesticide applications there is also a health concern. Many people in Vietnam, especially where I am based, have fears surrounding pesticides and their potential

NATURAL ENEMIES

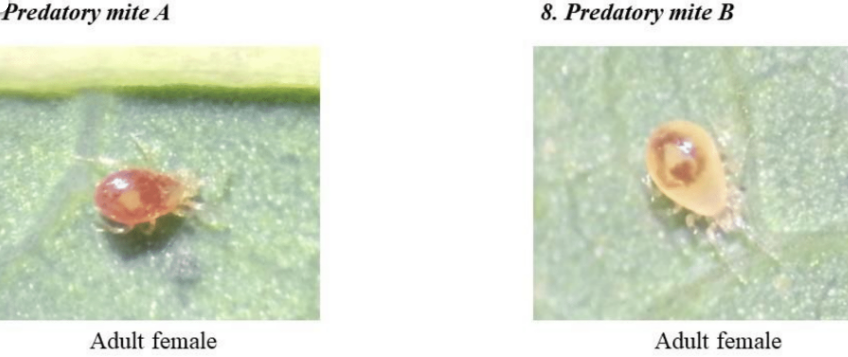

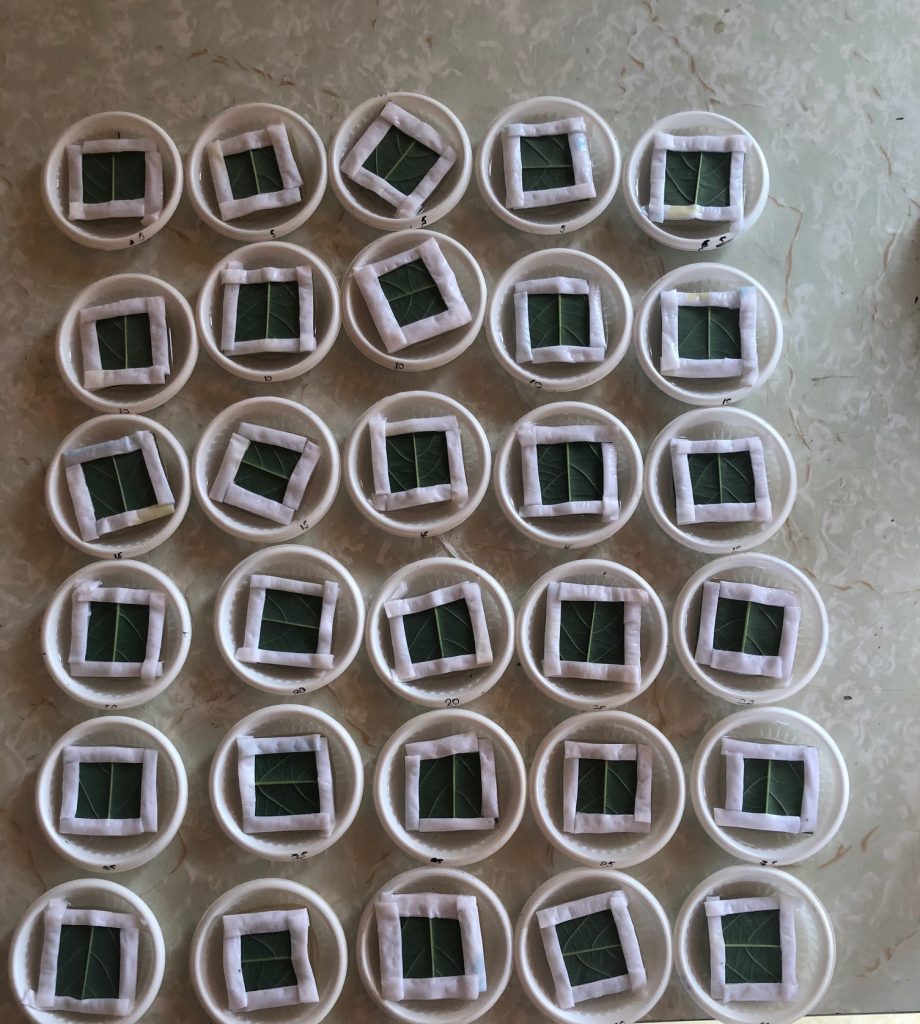

Predatory mites keep populations of spider mites in check, as do ladybirds, beetles and lacewing larvae. Managing mites requires preserving natural enemies; in most cases this means doing nothing to harm them, which means not using pesticides. The Project I am involved in is interested in using predatory mites as a biological control which if successful could eventually lead to farmers being taught how to raise predatory mites for release into their fields to control red spider mite numbers.