Source: Sustainable Travel Ireland

Should the focus be on preventing food waste in our homes and less on methods of tackling food waste when it occurs?

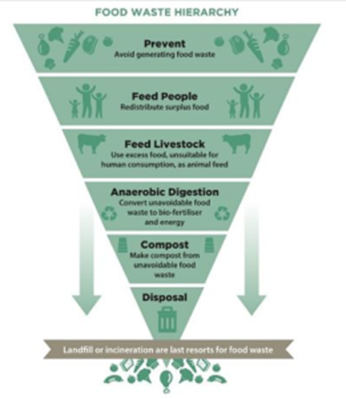

The Waste Action Plan for a Circular Economy: Ireland’s National Waste Policy, 2020-2025, provides a ‘food waste hierarchy’ for the prevention and management of food waste. It comprises: (1) Prevention – avoid generating food waste, (2) Feed People – redistribute surplus food, (3) Feed livestock – use excess food, unsuitable for human consumption as animal feed where appropriate and in accordance with feed safety regulations, (4) Anaerobic Digestion – convert unavoidable food waste to bio-fertiliser and energy, (5) Compost – make compost from unavoidable food waste, (6) Disposal – landfill or incineration are last resorts for food waste; see EPA diagram below.

This blog is focusing on the first priority of Prevention, targeting the household level, believing that if this were addressed (waste and its connection to diets), less focus would be required on the other 5 actions of the food waste hierarchy. This emphasis would have a positive knock on effect on food waste in the commercial sector, from retail and distribution to restaurants and food, as people’s diet choices and waste habits could be changed. This blog also laments the missed opportunity of not starting the Prevention journey in earnest during Covid-19.

Why reduce food waste?

Reducing food waste offers multi-faceted wins for people and planet, improving food security, addressing climate change, saving money and reducing pressures on land, water, biodiversity and waste management systems according to UNEP’s Food Waste Index Report launched in March 2021, and yet this potential has until now been woefully under-exploited. Why?

The science tells us that producing food from farm-to- fork involves intensive resources such as land, water, fertilizers, and fuels used for growing, harvesting, processing, packaging, transporting and storage and, therefore, it has a high carbon footprint. If not consumed, or recycled or composted, it ends up in landfill sites releasing methane, a greenhouse gas (GHG) that is many times more potent than carbon dioxide, increasing the carbon footprint of food further. Therefore, addressing food waste, ie preventing it happening in the first place, is both a smart environmental and economic action to take by all countries including Ireland. Where better to start that in our homes!?

For many, it is not only an environmental and economic issue, but a moral/ethical one with so many people living today in poverty. It is estimated that between 720 and 811 million people in the world faced hunger in 2020, and around 118 million more people were facing hunger in 2020 than in 2019. More than half of the world’s undernourished are found in Asia (418 million) and more than one-third in Africa (282 million),(FAO, 2021), yet 2.1 billion adults are overweight or obese, (2018 Global Nutrition Report; WHO/UNICEF/World Bank Group). Around 1 billion people still have insufficient access to food, while more consume low quality diets that contribute towards the development of dietary-related illnesses such as diabetesand heart disease (www.thelancet.com/ planetary-health Vol 5 July 2021).

A global study published in 2017 in the Lancet projected that if the trends seen at the time continued, by 2022 obesity in children and adolescents aged 5-19 years would surpass the share who were underweight for the first time. That prediction now seems certain to come true and yet globally nearly 22% of children under 5 years were affected by stunting in 2020, and 6.7 % by wasting,(FAO, 2021) The great global moral and ethical dilemma!

Some global, EU and Irish facts about food waste

The UNEP report referred to above estimates that around 931 million tonnes of food waste was generated in 2019. This weight roughly equals that of 23 million fully loaded 40-tonne trucks — bumper-to-bumper, enough to circle the earth 7 times. Sixty one (61) per cent of this waste came from households, 26 per cent from food service and 13 per cent from retail. “This suggests that 17 per cent of total global food production may be wasted (11 per cent in households, 5 per cent in food service and 2 per cent in retail”: UNEP, 2021. An estimated 8-10 per cent of global greenhouse gas emissions are associated with food that is not consumed (Mbow et al., 2019, p. 200). Unfortunately, none of the Nationally Determined Contributions to the Paris Agreement mention food waste (and only 11 mention food loss) (Schulte et al., 2020).

One surprising fact from the report is that household food waste generation per capita is broadly similar across country income groups, suggesting that action on food waste is equally relevant in high, upper‑middle and lower‑middle income countries. This indication is different to earlier narratives suggesting that most of the waste in developed countries was at the end of the food chain stage, towards consumption and retail stage while in developing countries most waste occurred at food production, post harvest, storage and transportation stages.

Another, perhaps not so surprising finding in the report, is that previous estimates of consumer food waste significantly underestimated its scale. While UNEP acknowledges that data don’t permit a robust comparison across time, food waste at consumer level (household and food service) appears to be more than twice the previous FAO estimate. (Gustavsson et al., 2011).

Is Ireland tackling food waste at household levels?

The 2015 European Commission’s Circular Economy package requires an EU-wide food waste reduction of 30% by 2025 and 50% by 2030, so Ireland will be obliged to follow suit. The revised Waste Framework Directive (2018/851/ EC) explicitly requires that “Member States shall adopt specific food waste prevention programmes within their waste prevention programmes”. More recently, in the Second Circular Economy Action Plan, the European Commission proposes a food waste reduction target via its ’Farm to Fork Strategy’.

See link to EU Platform on food losses and food waste, https://europa.eu/!UKD737

According to Ireland’s Waste Action Plan for a Circular Economy,2020-2025, Ireland generates approximately 1 million tonnes of food waste per year (not including wasted food from agriculture), which represents a carbon footprint as high as 3.6 Mt CO2eq. It claims that around 40% of this comes from food processing operations, while 60% of it comes from the household and commercial sector. Current household food waste is estimated to be 250,000 tonnes per annum, (EPA 2021). The average Irish household throws out 150 kg of food waste each year at a cost of approximately 700 euro (EPA 2021). Household consumption of food and drink was valued at €10.5 billion in 2018, of which approximately 51% was imported,(CSO). Current food waste in the commercial sector is estimated to be 303,000 tonnes per annum (100,000 tonnes from retail and distribution and 203,000 tonnes from restaurants and food service), (EPA, 2021). There is a significant amount of food waste not being segregated for separate collection, with over 406,000 tonnes of food waste in residual and recycling bins, (EPA 2021). So the management of waste in addition to prevention is also a significant issue. According to the Climate Change Action Plan, 2021, published in November 2021, waste emission in 2018, per person was 0.2t. CO2eq. It claims that waste emissions per head are lower in Ireland compared to the EU average.

Worthy of note is that the Climate Plan sets out a target to reduce food waste by 50% by 2030, in the chapter on the Circular Economy. It also states that the priority areas for prevention planning are in plastics, food, construction and commercial waste and yet the only action proposed in the plan to reduce food waste appears to be action 420: “Develop a Food Waste Prevention Roadmap that sets out a series of actions to deliver the reductions necessary to halve our food waste by 2030 and promote our transition to a circular economy”. In other words, the Road Map has yet to be developed and we have eight years to reduce food waste by 50% by 2030. It is not clear what should be used as the baseline year value. This process could have started with collecting the relevant data (see below) engaging the households, and could have gone even further, in using the data to define the Road Map and to start its implementation during covid-19. Moreover, it could have widened the household research to look at diets and how food options and waste contribute to climate change. What a missed opportunity!

Ireland has also committed to implementing the global Sustainable Development Goals. Goal 12.3 (SDG 12.3) commits countries to halve food waste at the retail and consumer level and to reduce food loss across supply chains by 2030. The UNEP report referred to above also sets out a methodology to assist countries to measure food waste, at household, food service and retail level, in order to track national progress towards 2030 for SDG 12.3. Countries are required to put in place measures to collect the relevant and accurate data. The report has an appendix that uses existing, available data to try to measure food waste in countries around the world. It used 2016 data for Ireland (where the data has been labelled as having medium confidence) and shows the Household Sector having 54.70 adjusted kg/capita/year and 56.15 in Food Services, which is quite different to the EPA 2021 estimate above. Hence, there is a clear need to collect accurate data at household level to meet our EU and global obligations.

Source : EC Key findings – Champions 12.3 progress report 2018

Availability of reliable data is clearly an issue for many aspects around food waste. Under EU waste laws, from 2020, Member States are required to gather data on food waste across the value chain, including from primary production, processing and manufacturing, retail and other distribution of food, restaurants, food services, and households. These statistics must be submitted to EuroStat from 2021. Collecting such data in partnership with households during Covid-19 was a real opportunity that could have been taken and obligations fulfilled.

A missed opportunity during Covid-19 to have conversations around food waste in our homes?

Within the context above, and especially now with Covid- 19, and given the emphasis on climate change, the time is surely right to ask ourselves the tough question, why do we waste food in our homes in this modern era? Are our eating habits contributing to food waste? Do we tend to cook too much food and not use the left-overs? Do we buy fresh vegetables with great intentions and somehow never get around to cooking them? Is the retail pre-packaging of food an issue?Are our methods of storing food healthy? Is there a connection between what we eat (our diet) and the amount of food we waste? What would make us change our diet? What constraints are preventing us from changing our diets? Is it medical, economic, psychological cultural, or something else? How might we overcome these issues? Where does our food come from? What can be grown and produced in Ireland so as to have a lower carbon footprint than imported food? Do we know the nutritional values of what we eat and our daily recommended requirements? Are Irish citizens, at all levels, ready to move to a plant based diet? What are the advantages of a plant based diet? Will this have any impact on food waste in our homes?

Do we know the carbon footprint of each food item and how it is contributing to climate change? Do we know which meal of the day creates the most waste? Which food items generally end up as waste? Can any of this be managed or avoided? Have we ever tried to put a monthly cost on our household waste? Or is it simply that we really have not thought about the impact of our food choices and our waste? Has it become an unquestioned habit? Do we leave these tough questions to be asked and answered by someone else, either in the school, hospital or by the public service? Is it time to create and inspire national interest around these questions, focusing at the household level, encouraging them to lead the discussions and conversations around food options, food waste and the environment?

A missed opportunity during Covid-19 to develop a Food Waste Prevention Road Map

Did we miss the opportunity in Covid-19 to ponder the questions above and many more, to understand the reasons why we waste food in our homes, throughout the year, across the different age groups from infancy to old age? Did we miss the opportunity to engage households to gather the much needed information to understand the reasons for food waste, the connection with our diets and their nutritional and carbon composition, and the positive aspects of plant based diets? Did we miss a period of awareness and learning where we could have sought out together, and implemented solutions, using the many communication channels through which to share our stories? I believe the time was right during Covid-19 and we did indeed miss that opportunity. Had we done that over the past two years we may have had the basis from which to define the solutions. This opportunity might have provided the foundation for changing not only our food waste patterns, but also our food choices while achieving our recommended nutritional intake at the same time as lowering our carbon footprint in the process. In addition, we could have met (with accurate data and action) some of our global, EU and national targets that we has signed up to as a nation. I am sure the many lessons learned would be compiled into many Christmas volumes for the unconverted.

Regrettably, Ireland has only begun to plan to prevent food waste at household level but it is to be hoped that the Food Waste Prevention Road Map will soon be developed with the involvement of households using many innovative communication techniques. Let us all advocate for this before another opportunity is missed.

References:

https://www.gov.ie/en/publication/4221c-waste-action-plan-for-a-circular-economy/

https://wedocs.unep.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.11822/35356/FWA.pdf

https://www.mywaste.ie/about-mywaste

https://www.gov.ie/en/publication/b542d-whole-of-government-circular-economy-strategy-2022-2023-living-more-using-less

https://www.gov.ie/en/publication/6223e-climate-action-plan-2021/

https://www.cso.ie/en/csolatestnews/pressreleases/2021pressreleases/pressstatementfoodandagricultureavaluechainanalysis/

http://www.foodwaste.ie/wp-content/uploads/2010/06/SI-508-of-20091.pd

https://www.epa.ie/publications/circular-economy/resources/EPA_Circular-Economy-Programme_2021-2027.pdf

https://ec.europa.eu/food/horizontal-topics/farm-fork-strategy_en

http://www.rediscoverycentre.ie/un-produces-bleak-statistics-for-irish-food-waste/

https://wrap.org.uk/about-us/governance

https://foodwastecharter.ie/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Charter-Food-Waste-Recording-Sheet.pdf

https://www.economist.com/the-world-ahead/2021/11/08/obese-children-will-outnumber-the-underweight-for-the-first-time

http://www.foodwaste.ie/

https://www.sustainabletravelireland.ie/training

Ireland Statutory Instruments , S.I. No. 508 of 2009 : Waste Management ( Food Waste (regulations 2009).