While insect consumption is somewhat of a novelty in the west, it has actually been a part of human cuisine for a long time, especially in Africa, Asia, and Northern America. And in Thailand specifically, insect consumption still plays a major part in everyday nutrition. As such there are more than 20000 registered insect farming enterprises, in Thailand. In the past insects were considered food for the poor, however, in the past decades, that notion has become outdated, and insects have become an affordable, nutritious and variable meal or snack.

A lot of insects are simply gathered from the wild, such as grasshoppers, bamboo caterpillars, silkworms, water scavenger beetles and others. While a few insects are properly reared in facilities, most common are crickets and palm weevil larvae. With crickets being more widespread in the north, and weevils in the south.

Initially, most farms were small-scale, private tanks, now however they are all medium to large-scale industries, either as a result of a community cooperative or a commercial endeavour. Now with 20000 farms operating more than 200000 rearing pens the annual production is measured at around 7500 tonnes.

Cricket farming

Proper cricket farming initially started in Thailand in 1998, the technology was developed at Khon Kaen University and then introduced to farmers and communities all over the country, quickly gaining popularity and acceptance.

Initially, three common native cricket species were used (Gryllus bimaculatus DeGeer, Teleogryllus testaceus Walker and T. occipitalis (Serville)), however eventually they were mostly replaced by the house cricket (Acheta domesticus) due to it’s preferred taste. Cricket rearing is relatively easy, eggs are placed in sand or similar substrate and after hatching the growing crickets are held in a variety of pens. Where they are generally fed chicken feed and a combination of fruit and vegetables. Once they are ready to harvest, they are simply gathered by hand and either thrown in water bags or frozen.

From large-scale farms, the crickets are usually sold to wholesale buyers, or sometimes directly to consumers or for feed. After one cycle (45 days) farmers can expect a net profit of 50%. A medium-sized farm, producing 500 to 750 kg of crickets can expect a revenue of THB 30000 (816.77 euro1) to 70000 (1905.80), and THB 150000 (4083.86 euro) to 350000 (9529.01) per year if four to five harvesting cycles are involved. Large-scale farms can produce up to 2 tonnes of crickets per harvest cycle.

1as of August 2022

Of course, as with all industries, certain threats can arise with cricket farming.

The high price of protein feed can make up almost half of production costs, making the industry vulnerable to chicken feed prices. And research is required for better feed alternatives.

Disease problems are fairly rare amongst crickets, but undoubtedly with the high population density in rearing facilities and the consequences of human intervention, diseases, infections or contamination of some kind are likely to arise. Meaning that vigilance is always required throughout the whole industrial process.

Palm weevil farming

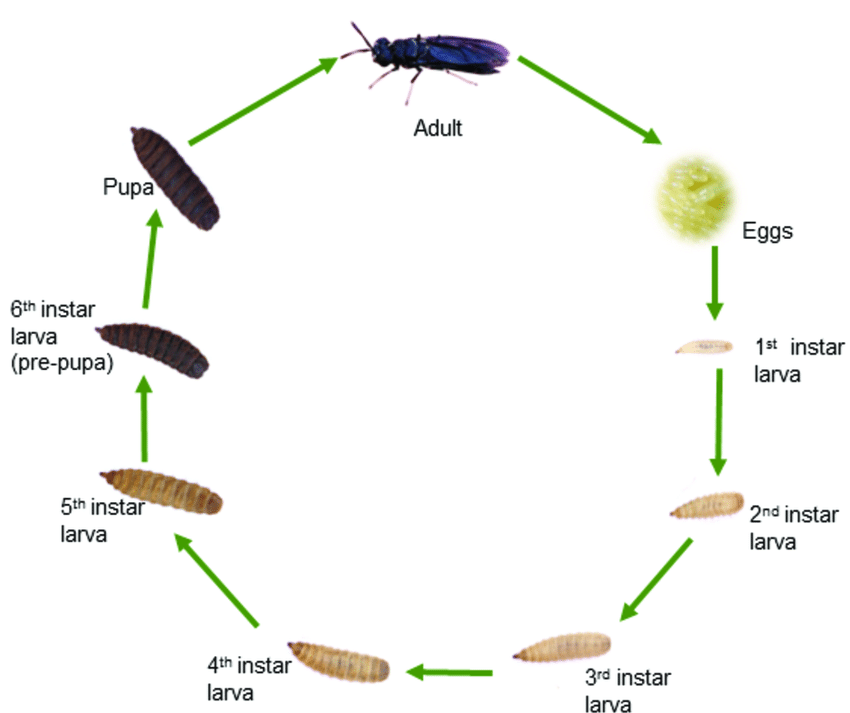

The Palm weevil (Rhynchophorus ferrugineus Olivier) has been farmed for home use by locals of southeast Thailand since 1996, and later become popular and spread around 2005. Data on palm weevil farming is limited, it is only known that in 2011 120 farmers produces 43 tonnes of palm weevil larvae using 4289 rearing basins. The insect’s life-cycle is very reliant on the lan phru tree, and as such currently cannot spread to regions where the tree is absent, and industrial production is also limited as a result.

Traditionally rearing is done directly in palm trunks or stems, which serve as both feed and housing. Several pairs of female and male adults are placed into drilled holes and then sealed, only water is applied twice a day and after 40 to 45 days the larvae can be harvested with a yield of approximately 2 kg per trunk.

A more modernized method utilizes large plastic containers with ground palm stalks and pig feed. With this method after 25 to 30 days each container produces 1-2 kg of larvae.

The net profit of the traditional method, with an average of 350 to 400 trunks used, per harvesting cycle is around THB 143000 (3893.28 euro) – 164000 (4465.02). While the basin method has a net profit of around THB 84000 (2286.96 euro)- 126000 (3430.44) from 200 – 300 basins. The higher profit of the traditional method is due to the lack of feed cost and the ability to reuse trunks, this however does come at the cost of cut down trees.

The reliance on the plan phru tree is a clear limitation on farming, and since the traditional method is more profitable and easier to carry out, the number of palm trees is steadily declining, prompting a need for either a feed alternative or limitations on traditional farming methods.

Insect farming is a very large industry in Thailand, and while it may still need development in certain areas, it is a prime example that insect farming is a promising industry that deserves to be looked into and developed.

References:

- Hanboonsong, Y., Rattanapan, A., Waikakul, Y. & Liwavanich, A. 2001. Edible insect survey in Northeastern Thailand. Khon Kaen Agriculture Journal, 29(1): 35-44. (In Thai.)

- Halloran, A., Hanboonsong, Y., Roos, N. and Bruun, S. (2017) ‘Life cycle assessment of cricket farming 617 in north-eastern Thailand’, Journal of Cleaner Production, 156, 83-94.

- Reverberi, M. (2020) ‘Edible insects: Cricket farming and processing as an emerging market’, Journal of Insects as Food and Feed, 6(2), 211 -220.