The full impact of Climate Smart Villages is challenging to evaluate leading to limited literature on this topic. However, have experienced success in increasing community’s climate resilience, crop production, economic well-being, and adaptive capacity. The success in these areas means that Climate Smart Villages are beneficial in adapting agricultural systems in the impacts of climate change. As Climate Smart Villages continue to evolve, the most successful strategies can continue to be expanded, becoming more efficient and in turn generating more targeted efforts that lead to increased success. Furthermore, projections indicate that the impacts of climate change will become far more severe over the next decade (CCAFS, 2021). Meeting global agricultural needs in the context of climate change requires that all strategies that have the potential to mitigate and adapt to climate impacts need to be used. CSV’s can be a cornerstone of these efforts as they continue to scale up.

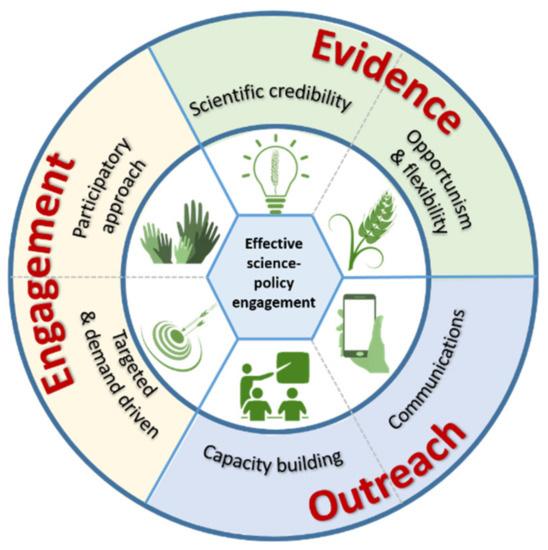

There is a need for more research to be conducted on all aspects of CSV’s. Climate Smart Villages are a relatively new development in agricultural climate change adaptation. Lack of literature in this area is in part because CSV’s have only been around for a decade. However, a larger explanation for the lack of literature on CSV’s is due to the challenges that exist in evaluation across systems. Evaluations of CSV’s that assess multiple projects, underestimate the complex social differences that exist in each agricultural community and system (Taylor & Bhasme, 2020). The variations between CSV’s is well documented in literature and especially in literature evaluating the impact of CSV’s on certain aspects of climate resilience. However, when variations between CSV’s are mentioned in the literature, the conversation often surrounds differences in cropping systems or differences in the climactic impacts that communities face. While there is a need to point out these differences when evaluating multiple agricultural systems, analysis of the social differences between two communities and the effect this has on cropping systems or response to climate impacts, is underreported (Taylor & Bhasme, 2020). The complex nature of analyzing the social context of a CSV means that there is no easy solution to overcome this. However, progress can be made in this area by expanding more in-depth participatory evaluation. When assessing any element of climate resilience, quantitative analysis alone does not portray an accurate elevation of the community’s climate resilience if the community itself does not hold the belief that the implemented adaptation strategies are promoting climate resilience (Bahinipati et al., 2021).

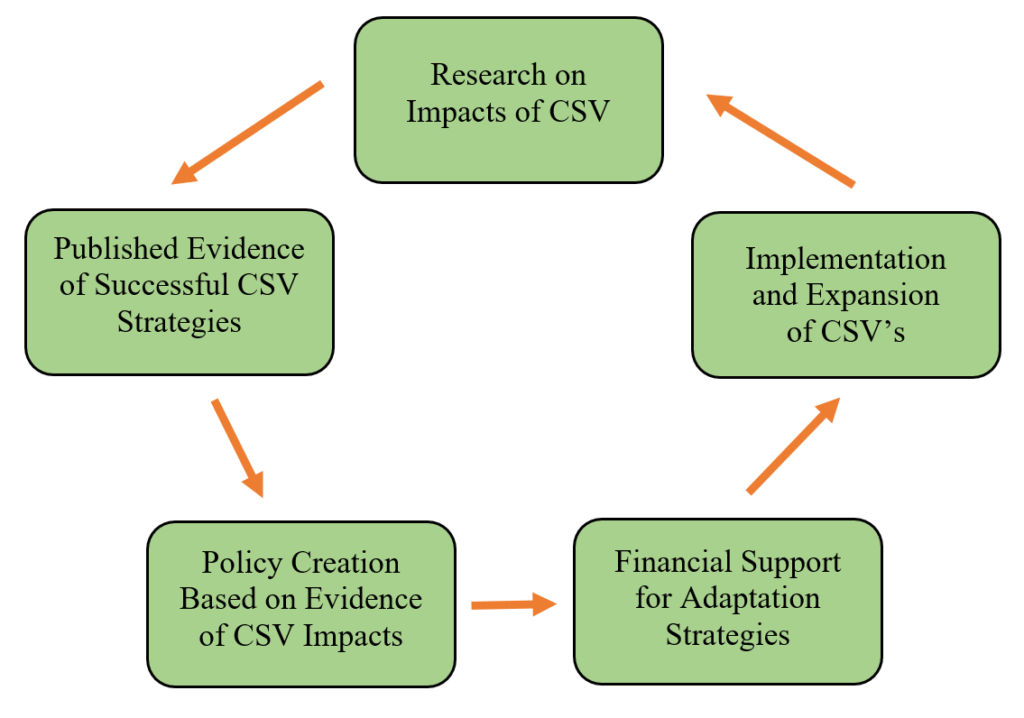

Literature and research surrounding CSV is also lacking regionally and in magnitude. There is significant amount of literature globally surrounding both CSA and CSV. In a web search for “Climate Smart Villages”, google indicates that there are more than 10 million results returned in less than one second. This alone would indicate that CSV is a well-documented area of study with in-depth reporting. However, when specifically looking for peer-reviewed, evidence based, publications on Climate Smart Villages, there is a shortage of literature. Brochures, web-pages, images, and opinion pieces, all play an important role in communicating what CSV’s are providing insight to the general public. However, to increase the scientific findings around CSV that can produce findings leading to recommendations for scaling and policy, more in-depth, peer-reviewed scientific literature is required. This includes more scientific evaluation-based literature by region. When dividing the existing CSV literature used in this systemic literature review, by region, only a handful of papers exist for each. While it is important to note that additional scientific papers on CSV impacts do exist, the figure shows the primary data, peer-reviewed papers from Web of Science, Scopus, Google Scholar, and CGSpace. Across these four major scientific databases, more than 41 papers should exist as this does not generate enough evidence to drive widespread policy and scaling. Regardless of a comparison of the amount of peer-reviewed literature existing per region, more publications are needed in every region to enable evidence-based changes to scale up the successful components of CSV and generate economic and political support for CSV expansion.

Lack of literature surrounding CSV’s is one of the biggest limitations facing CSV. Regardless of the evaluations of CSV’s impact on increasing climate resilience, adaptive capacity, social issues, and GHG mitigation, there is not sufficient evidence to conclude that these evaluations are indicative of the impact of CSV’s globally. The overwhelming need to adapt agricultural systems over the coming decade as population increases and climactic impacts worsen, means that all research and literature in all areas of climate change and agriculture need to be expanded. This holds true for Climate Smart Villages, as a dramatic increase in literature and research surrounding the topic is needed to increase the rates of implementation of successful climate based agricultural adaptations.

Policy and Scaling

Scaling of Climate Smart Villages is a challenge that is documented in the literature surrounding the topic. Agriculture is a sector that especially has a challenge with scaling because agricultural systems vary from region to region, so success in one agricultural system is not guaranteed to transfer to another. Furthermore, scaling requires financial backing and the resources needed for implementation. The high cost of inputs required means, widespread scaling does not happen naturally but rather requires policy. While the creation of policy has the potential to generate major scaling of CSV’s, promoting policy-based changes is a major obstacle. The relationship between policy and scaling is not only a challenge for climate based agricultural adaptations, but rather scaling of any climate or environmental action strategies (Srinivasa et al., 2016).

Increasing policy for scaling of CSV’s is a major need to increase the uptake of successful agricultural adaptations as climate impacts worsen. Generating policy solutions requires sufficient evidence of successful strategies that are proven to make major and immediate impacts. Furthermore, public support is necessary to move policy along, resulting in implementation. As the impacts of climate change become more extreme and the percentage of the planets population directly affected by these impacts grow, public support for climate change mitigation strategies increases. However, increase in public support has created pressure on governments to implement policy to reduce GHG emissions, rather than extensive climate adaptations to existing systems. This is especially true in agriculture as urbanization of global population has created disassociation between society and agricultural production systems. Support for GHG mitigation therefore manifests itself in carbon reduction targets for industry and automotive sectors (Aggarwal et al., 2018).

The use of climate change mitigation as the driving force of policy creation for CSV implementation does not carry enough weight in today’s society to generate widespread and extreme change. However, the targets of food security and poverty drive more immediate and widespread agricultural change (Aggarwal et al., 2018). Mainstreaming policy creation for the scaling of Climate Smart Villages is much more achievable if evidence of increased food security and reduced poverty in CSV’s is clear and compelling. Therefore, as mentioned above, there is a need for increased research-based published evidence on the correlation between CSV’s and farmers livelihoods and food security. Generating support for poverty and hunger policy is much more achievable as these issues are seen universally as areas of need (Aggarwal et al., 2018). Climate change mitigation policy support has increased as climate change has become a bigger reality, but support for policy is this area often falls along party lines, especially in countries with large economies (Srinivasa et al., 2016).

Bahinipati, C. S., Kumar, V., & Viswanathan, P. K. (2021). An evidence-based systematic review on Farmers’ adaptation strategies in India. Food Security, 13(2), 399–418.

Aggarwal, P. K., Jarvis, A., Campbell, B. M., Zougmoré, R. B., Khatri-Chhetri, A., Vermeulen, S. J., Loboguerrero, A. M., Sebastian, L. S., Kinyangi, J., Bonilla-Findji, O., Radeny, M., Recha, J., Martinez-Baron, D., Ramirez-Villegas, J., Huyer, S., Thornton, P., Wollenberg, E., Hansen, J., Alvarez-Toro, P., Yen, B. T. (2018). The climate-smart village approach: Framework of an integrative strategy for scaling up adaptation options in agriculture. Ecology and Society, 23(1).

Srinivasa Rao, C., Gopinath, K. A., Prasad, J. V. N. S., Prasannakumar, & Singh, A. K. (2016). Climate resilient villages for sustainable food security in tropical india: Concept, process, technologies, institutions, and impacts. Advances in Agronomy, 101–214.

Taylor, M., & Bhasme, S. (2020). Between deficit rains and Surplus populations: The political ecology of A climate-resilient village in South India. Geoforum.