Zoonoses may be a new term to many before the COVID-19 pandemic, but it may soon be more than a once-in-a-lifetime encounter. Zoonotic pathogens cause about 20% of illness and death in developing countries. Climate change, deforestation, globalization, urbanization, growth in population, pathogen mutation, vectors, human behavior and culture, and mobility all add to zoonotic infection and transmission.

The coronavirus is an enveloped, single stranded RNA (+ssRNA) virus of the order Nidovirales and the family Coronaviridae. In the 1930s, coronaviruses were isolated from poultry, and by the 1960s, they were first identified in humans. It was estimated that until 2002, human coronaviruses were responsible for causing 15 to 25% of all common colds and only triggered mild respiratory tract diseases. In 2002, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS-CoV) emerged, causing a much more significant respiratory illness. Other coronavirus outbreaks include the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS-CoV) in 2012 and the current SARS-CoV-2 that appeared in 2019.

Adopting a “One Health” approach would be beneficial to combating zoonosis spread. Though this approach is now being more widely discussed, it has been around since the 1800s where scientists recognized the similarity between human and animal disease processes. RNA viral diseases are particularly fickle as they are susceptible to mutations, allowing for new, possibly more infectious variants to emerge. If high-risk viral pathogens were identified before infecting humans or early on in the process, it could allow for the possibility to prepare and create plans on how to combat the forthcoming disease. Currently, there is little surveillance on emerging infectious viruses being completed. Though the 2003 SARS-CoV was reported as being ‘successfully controlled,’ over 8,000 people from 37 countries were infected, 774 died, and an evaluated cost of 80 to 100 billion USD loss. The global impact of SARS-CoV-2 is already exponentially more significant, and the end of the damage is not in sight.

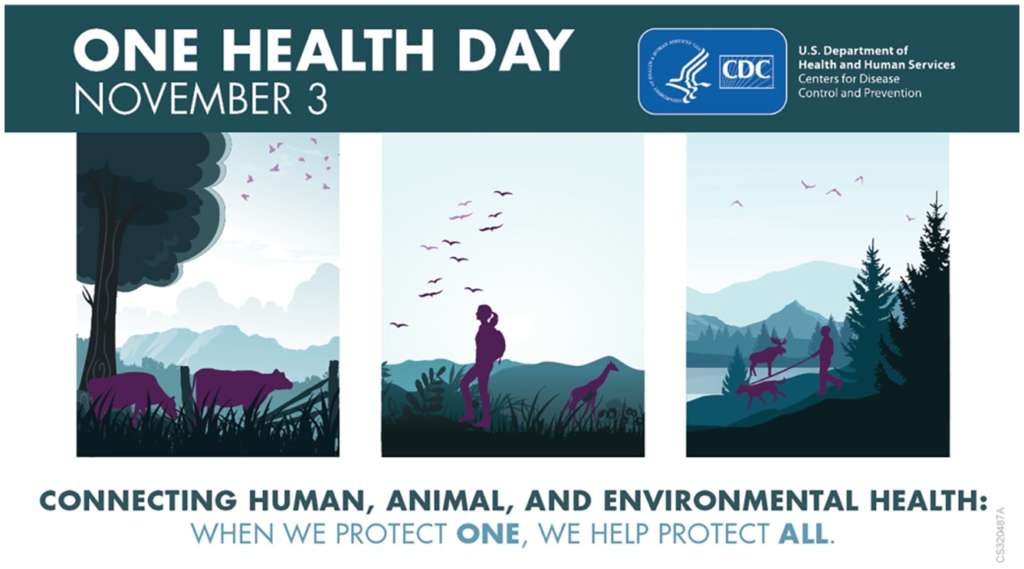

There must be an increase in collaboration among animal, human, agricultural, and environmental health organizations. Clear communication could allow for improved detection and mitigation plans for future infectious disease outbreaks. The “One Health” approach works at local, regional, national, and global levels emphasizing and recognizing how people, animals, and the environment are closely interconnected and constantly interacting. This approach is becoming increasingly more critical as ~70% of emerging and re-emerging pathogens are zoonotic. The globe must recognize that human activities like deforestation, commercial agriculture, antibiotic use in industrialized livestock farming, anthropogenic climate change, and human consumption and trade of food all impact the spread of zoonosis and human health. If individuals better understood that these activities impacted their health, and media and organizations framed the discussion that way, people may be more concerned.

Some ‘One Health’ initiatives that were introduced by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), which is the national public health agency of the United States.

- Advanced Molecular Detection (AMD): A relevant One Health issue is antibiotic-resistant bacteria that have evolved to become immune to drugs that were established to kill the bacteria. Whole genome sequencing (WGS) is a scientific tool that grants scientists the ability to look at antibiotic resistance and exactly how it emerges. The multidrug-resistant Salmonella Heidelberg outbroke in 2015 through 2018, and WGS was able to identify that the outbreak in people was connected to dairy calves.

- China’s Stepwise Approach to Rabies Elimination (SARE): China had the second-highest rate of human rabies deaths on the globe in 2015. China pledged to the World Health Organization (WHO) that by 2030 they could reach zero human deaths caused by canine rabies. As a result, China’s Center for Disease Control (China CDC) and the US CDC China office united to host a SARE Workshop in 2019.

- Addressing Zoonotic Diseases in Uzbekistan: Uzbekistan has previously struggled with preventing and controlling zoonotic diseases. There are limited surveillance systems and deficient veterinary and health systems in the country. Livestock production is essential for the country’s economic growth, so the CDC, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), and the Defense Threat Reduction Agency (DTRA) have collaborated with the Uzbekistan government to prevent, track, and test zoonotic diseases.

- Educating Youth: 2011 saw an outbreak of influenza A, originating from exposure to pigs. The 4-H (Head, Heart, Hands, and Health) in the United States is a program that encourages youth to look at critical societal issues, like community health inequities and advocating for equity and inclusion. The FFA (Future Farmers of America) is also a youth organization that focuses on agriculture and leadership. The CDC and United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) work with these youth organizations in rural America to educate about zoonoses prevention.

References

Muraina, I. A. (2020). COVID-19 and zoonosis: Control strategy through One Health approach. Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Medicine, 13(9), 381.

One Health. (August 26, 2021). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/onehealth/index.html

Strengthen ‘One Health approach’ to prevent future pandemics – WHO chief. (17 February 2021). United Nations. https://news.un.org/en/story/2021/02/1084982