In order to compare one type of diet against another in terms of sustainability, health, environmental impact, etc., each diet must be classified based on its common components. This is also known as typologising, and it helps us simplify complex things so that general patterns can be analysed. One well-known example of this in the food world is the Mediterranean diet. My guess is that phrase brings certain foods to mind — maybe olive oil, seafood, or certain vegetables. Many of us are familiar with this diet because it has been typologised, researched, and widely promoted for its health benefits. So, what about globalized and traditional diets?

Globalized vs traditional

Globalized diets, also known as “industrial,” “western,” “modern,” “urban,” or “commercial” diets, are characterized by high intake of processed foods, fats (particularly saturated), domesticated animal-source foods, sugar, and refined grains, as well as low intake of whole grains, vegetables, and fiber1, 2. In the literature, globalized diets are often discussed in terms of their departure from traditional diets, the characteristics of which are essentially the opposite of globalized diets (high in vegetables, fiber, whole grains and low in fats, processed foods, sugars, refined grains, and animal-source foods)3.

Globalized diets are so called because they are more often found in urban areas and are seen as a product of industrialization and urbanization. As areas urbanize due to population growth and human migration, demand for food is higher and food systems respond by making a variety of foods available. It’s important to note that, while this increases the availability of processed foods, animal-source foods, and others that contribute to a less healthy and less sustainable diet, many urban areas also have higher availability and variety of fruits and vegetables, showing that urbanization can also provide unique benefits to dietary health and sustainability. On the other hand, these fruits and vegetables are sometimes pricier and of lower quality than those in non-urbanized areas4. Components of globalized diets, such as processed foods, ready-to-eat meals, refined grains and sugars, and animal-source foods, also tend to be more affordable in urban areas5. Cost can influence behavior through two cognitive routes: first, even when urban dwellers are inclined to eat a more traditional diet, affordability might dictate that they choose globalized diet components instead; second, migrants in urban areas might have had a harder time affording more globalized foods (i.e. meats) before moving, and are therefore inclined to indulge in them once they’re affordable5. And, we haven’t touched on one key factor in the rise of the urban diet: the allure of globalized foods. After all, our hungry animal instincts love salt, sugar, and fat, so we tend to want the burger and chips before wanting the vegetable stir-fry.

So, we seem to have this binary, with globalized diets on one end and traditional on the other, fully defined and functioning as expected. Right?

Not quite.

The challenge of the dietary spectrum

The problem with typologising something as complex and variable as diet is that it puts aside nuance in the interest of order. It’s important to remember that we are generally talking about dietary components, or the food items that make up a person’s diet, and not the way they’re prepared, eaten, or wasted, which are integral parts of dietary behavior and can impact sustainability and health. Also, when we define diets, we’re talking about trends and not universal truths. For example, while globalized diets are more common in urban areas, not every urban dweller consumes a globalized diet. Furthermore, it’s safe to assume that not every urban dweller who does consume a globalized diet does so in the same way; some might consume a lot of meat but few processed foods, while others follow a vegan diet but eat a lot of processed food. If we scale up this thinking from the individual person to the individual urban area, we find the same nuance. Some urban areas do not tend toward globalized diets as they grow; in fact, a study on urbanising food systems in Indonesia found that only one of thirteen urban areas showed signs of transitioning toward globalized diets6. Time and circumstances can also impact diet on individual and city levels, such as the length of time a person has lived in an urban area or food shortages from food system shocks like armed conflict or drought.

Traditional diets are similarly difficult to categorize. A romantic view of traditional diets gives us a picture of health and environmental balance—and a romantic view is essentially what our current traditional diet definition is. The reality is that traditional diets also sometimes contain high levels of animal-source foods, fats, or other elements usually considered globalized. Also, depending on the place, the time, and the circumstances, some traditional diets can lack variety and leave the eater lacking certain nutrients.

In short, people are all different and urban areas are all different, and this nuance is critical when it comes to shaping policy and creating interventions that can help us move toward food system sustainability.

Why diet definitions matter in food systems transformations

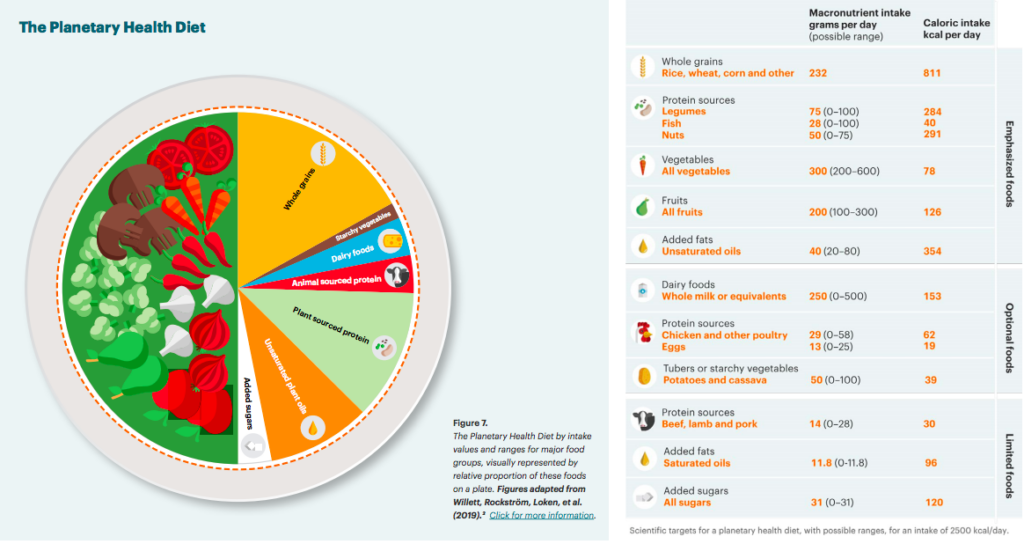

Using diet typologies paired with dietary guides for human and planetary health, such as the one below from EAT-Lancet, can help us develop an understanding of where we are and where we need to go. If we compare globalized diets, traditional diets, and the EAT-Lancet guide, we can theorize that, because traditional diets more closely match the healthy guidelines, they are better or our health, better for the planet, and should be promoted.

This understanding can help us create policies and interventions for food systems that help prioritize the right type of diet. But here’s the nuance: if we happen to be working in an urban area where globalized diets are less common, or one where social or financial factors dictate food choices, our policy or intervention promoting traditional diets is likely to be a waste of energy and resources if it is not properly targeted. If we happen to be working in an urban area where traditional diets lacking variety and globalized diets intersect, then there will likely be a sweet spot between these two diets where human and planetary health are optimized. The possibilities for unique situations are almost endless, and it is therefore imperative that policies and interventions for specific urban areas are built upon research from that area.

What’s in a name?

In research, it’s always important to be precise with our language. The nuance behind the names in dietary typologies shows us that even precise language sometimes requires more explanation, more digging, and more caution.

References

- Cyr-Scully, A., Howard, A. G., Sanzone, E., Meyer, K. A., Du, S., Zhang, B.,

Wang, H., & Gordon-Larsen, P. (2022). Characterizing the urban diet:

development of an urbanized diet index. Nutrition Journal, 21(1), 55.

https://doi.org/10.1186/s12937-022-00807-8 - Amorim, A. L., João Borges; Amaral Sobral, Paulo José. (2022). On how people

deal with industrialized and non-industrialized food: A theoretical analysis.

Frontiers in Nutrition, 9.

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2022.948262 - Batal, M., Deaconu, A., & Steinhouse, L. (2023). The Nutrition Transition and

the Double Burden of Malnutrition. In N. J. Temple, T. Wilson, J. D. R.

Jacobs, & G. A. Bray (Eds.), Nutritional Health: Strategies for Disease

Prevention (pp. 33-44). Springer International Publishing.

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-24663-0_3 - Holmboe-Ottesen G, Wandel M. Changes in dietary habits after migration and

consequences for health: a focus on South Asians in Europe. Food Nutr

Res. 2012;56. doi: 10.3402/fnr.v56i0.18891. Epub 2012 Nov 6. PMID:

23139649; PMCID: PMC3492807. - Berggreen-Clausen, A., Hseing Pha, S., Mölsted Alvesson, H., Andersson, A., &

Daivadanam, M. (2022). Food environment interactions after migration: a

scoping review on low- and middle-income country immigrants in high-

income countries. Public Health Nutrition, 25(1), 136-158.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980021003943 - Colozza, D., & Avendano, M. (2019). Urbanisation, dietary change and

traditional food practices in Indonesia: A longitudinal analysis. Social

Science & Medicine, 233, 103-112.

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.06.007