As you all know, this research was completed under the EcoFoodSystems project, a project involving researchers and investigators from a multitude of backgrounds. As my work comes to an end, I want to thank them all for the work they are doing and wish them the best of luck as they progress in the project.

The last post, I discussed the resilience framework we proposed, and therefore I feel I need to move on and tell you some results! There were many interlinked factors and research areas where I needed to pull information from, leading to a complex web of data which is linked together by the central theme of resilience. As such, please bear with my as I need to give you an overview of the food system and consumption patterns in Viet Nam in order to build an image of its resilience.

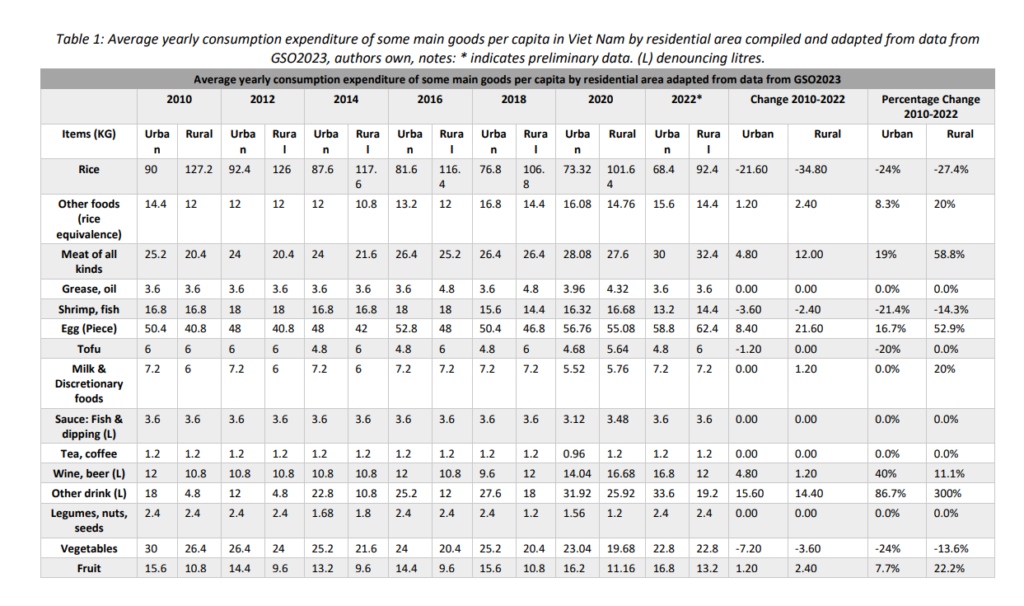

The below table is a research output from my project regarding the consumption of staple foods in urban and rural Viet Nam. This shows distinct disparities between the two regions. rapid urbanization, changing lifestyles, and increased disposable income have led to a shift in dietary preferences of both these urban and rural cohorts (Nguyen-Minh et al., 2023). Viet Nam’s main dietary staple is rice, leading to a widespread conceptualisation of national food security as rice self-sufficiency (Gorman, 2019), yet we will see that the country still imports other agricultural commodities like wheat, soybean, and maize (See the next blog!). Here we can see rice is declining in importance and is being relaced by other foods such as wheat and cassava.

This general reduction in total starch seems to have been replaced by animal-based foods as meat of all kinds has risen by more than 58 % for the rural population. Plant based food consumption in contrast has dropped almost 7 kilograms for vegetables with only a slight increase for fruit. Interestingly, urban areas tend to eat more fruit, vegetables, seeds and pulses while rural areas eat more tofu, discretionary foods, wine and beer, and fish.

One thing I would say is: Viet Nam saw an absolute improvement between 1990 and 2018 in its Alternative Healthy Eating Index (AHEI) rating, as one of the largest increases in the world while its neighbour the Philippines reduced (Miller et al., 2022). Despite this, the above table shows that there is an increase in generally less healthy foods which could mean that this improvement is now not as drastic as it was. As background, rates of obesity in Viet Nam are thought to be more concentrated in urban areas (Walls et al., 2009), which would make sense as obesity has been driven globally by economic development, urbanisation and women’s empowerment (Fox et al., 2019). Indeed, trends in both urban and rural Viet Nam indicate higher spending on sugar laden ultra processed foods have more than doubled in urban areas since 2010 and almost quadrupled in rural areas in the same time frame (VHLSS, 2020). So from a health and resilience perspective, this may be an area to note for Viet Nams government, especially regional governments in cities like Ho Chih Minh City and Hanoi!

From this brief overview we could assume, Viet Nam will have huge difficulties in the future as dietary changes have an effect on the population and imports, which will be talked about in the next blog!